PROJECT A119, A SECRET AMERICAN PLAN

By Antony Funnell

Long before JFK spoke inspiringly of sending humans to the Moon, the American intelligence community was concocting a very different plan.

Landing on the Moon was option B . Option A was to detonate a nuke on it.

In the late 1950s, Washington set in place a secret operation to examine the feasibility of detonating a thermonuclear device on the surface of our closest celestial neighbour.

It was codenamed Project A119.

Had it gone ahead, the expression “shooting for the Moon” would have gained a whole new meaning.

What might now seem unimaginable only makes sense in the context of the Cold War, historian Vince Houghton says.

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev meets with US president John F Kennedy in 1961.

Paranoia and distrust had reached fever pitch on both sides of the Iron Curtain by the late 1950s, and military one-upmanship was the order of the day.

The United States and its arch-nemesis the Soviet Union were at loggerheads, vying for global supremacy.

In 1956, while addressing a gathering of Western ambassadors, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev declared: “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you!”

His blunt message sent a chill down the collective international spine.

“These were times when true desperation played a role in our decision-making,” says Dr Houghton, curator of the International Spy Museum in Washington.

“We — the United States, Great Britain, the Allies — faced an existential threat to our existence. And when that happens, you make decisions you might not make in another circumstance.”

The situation went to Code Red in October of 1957 when the USSR successfully launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik.

The launch of the Sputnik satellite terrified the West, who thought they were better inventors.

The deployment caught the world by surprise. It was not only a great technological achievement, but was intended as a symbol of Russian superiority.

“The Americans and the West were terrified of the concept that potentially the Soviets had beaten us at our own game,” Dr Houghton says.

“We’d always been the big kids in science and technology, the people who had invented new and innovative things. All of a sudden the Soviets had beaten us into space.”

Doubling the sense of threat was the fact that Sputnik had been launched into orbit on what was essentially an intercontinental ballistic missile.

“The West was given a shock with the launch of Sputnik and very quickly the US Government flew into action and said we need to do something very spectacular,” Dr Houghton says.

“We need to do something so big that the whole world will know that this was just an anomaly, that Sputnik was just a blip, that the United States was still the big kid on the block.”

And with that, Project A119 was born.

The idea behind the project was ambitious, but simple — to create an explosion and lunar mushroom cloud so awe-inspiring and unavoidable that no matter where you lived on planet Earth, it would be impossible to ignore the extent of America’s military and technological might.

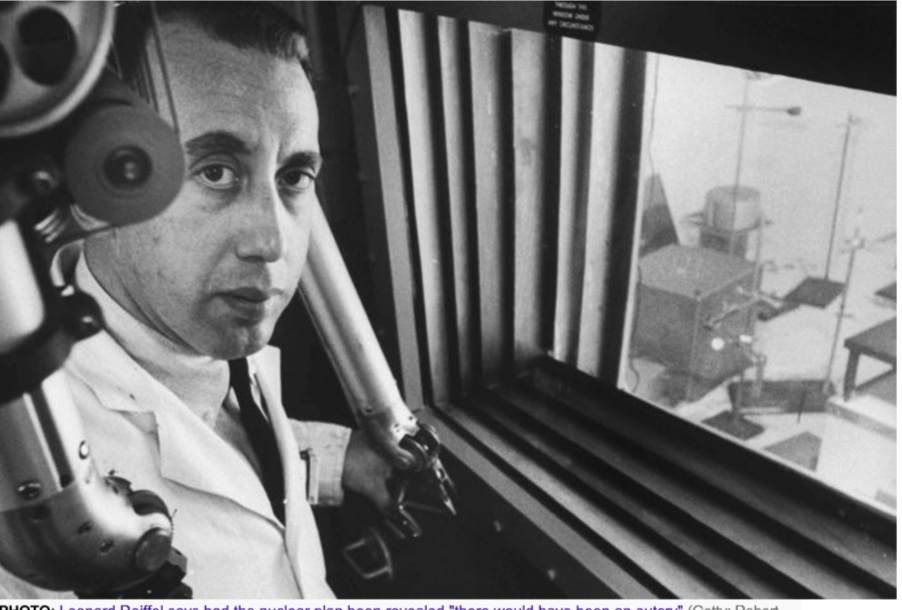

Leonard Reiffel says had the nuclear plan been revealed “there would have been an outcry”.

Appointed to lead the project was a physicist named Leonard Reiffel, who later went on to become the deputy director of the Apollo Program at NASA.

Carl Sagan, the famous author and celebratory science communicator, was also on the team, though at the time he was a young and little-known astrophysicist.

It’s been speculated that a secondary aspect of the project was to provide insights into the geological sub-structure of the Moon’s surface.

Protectors of the late Dr Sagan’s considerable reputation have suggested that his real interest was in exploring whether such an explosion might unearth signs of unknown lifeforms beneath the lunar crust.

A much younger Carl Sagan was part of the team.

Dr Houghton says when delivering the initial findings in June 1959, cost was among the major reasons why the project was scuttled.

But he says there were also concerns about damaging the lunar landscape.

“There were some scientists who said: ‘You know, we might want to walk up there some day. Maybe we don’t want to blow the hell out of it before we do,'” he says.

“But, again, Sputnik was so terrifying that a lot of people were willing to take that chance.

“A lot of people were willing to say: ‘You know what? The Moon’s big enough that we can nuke it and land on it at the same time, so let’s give this a shot.'”

Dr Reiffel’s secret report into the feasibility of a lunar detonation was eventually declassified in 2000.

It carried a rather innocuous title: A Study of Lunar Research Flights.

It suggested that detonating a nuclear device on the Moon was technically feasible, but it gave no substantive detail as to how it might be done.

The project never proceeded to operational phase.

Interviewed by The News Channel shortly after the report’s declassification, Dr Reiffel expressed his personal relief.

“I am horrified that such a gesture to sway public opinion was ever considered,” he said.

“Had the project been made public there would have been an outcry.

“I made it clear at the time there would be a huge cost to science of destroying a pristine lunar environment, but the US Air Force were mainly concerned about how the nuclear explosion would play on Earth.”

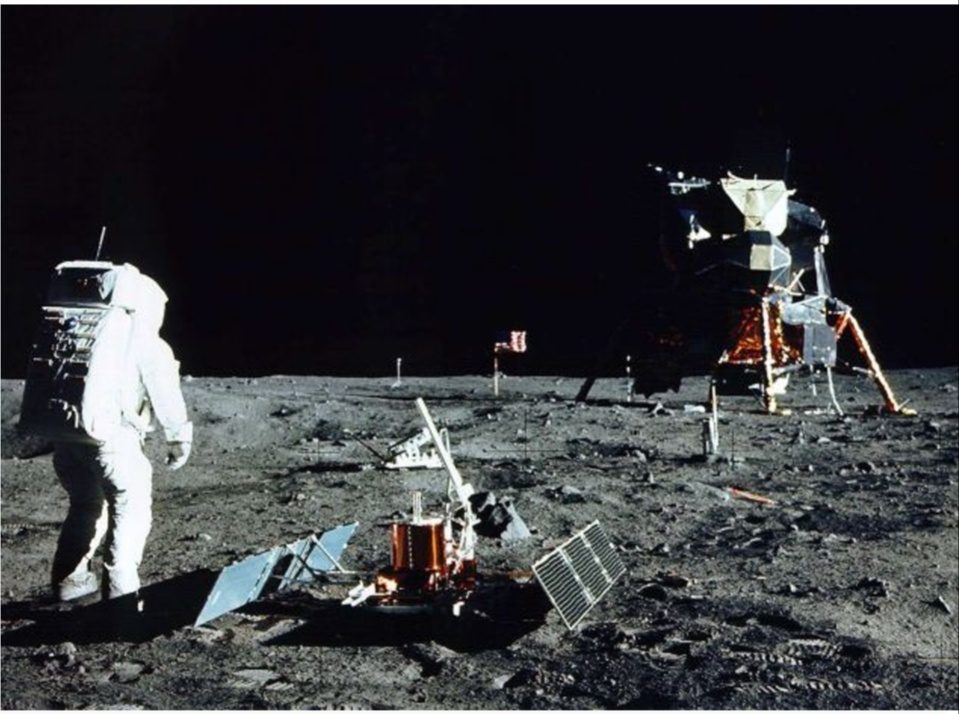

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr stands near a scientific experiment on the Moon’s surface.

Dr Houghton says it’s important to view Project A119 in its historical context.

He details the operation in a new book called Nuking the Moon, which examines a whole slate of radical intelligence projects that were set in motion during WWII and the Cold War, but which were never carried out.

Another involved dropping thousands of bats with incendiary devices strapped to their bodies over Tokyo and other Japanese cities.

While they might seem odd in hindsight, even extreme, he says the projects were born of a need to be creative in meeting a series of genuine military and political threats.

“That’s really what intelligence agencies are designed to do. They’re designed to provide policymakers with information that prevents us from getting surprised,” he says.

“So, [intelligence communities] better be thinking way outside of the box. They better be thinking not only about what technologies we might want to use one day, but also what technologies somebody might want to use against us.”

That may be true, but from a post-Cold War perspective, it’s hard not to conclude that, way back in the late 1950s, the Moon really did dodge a bullet — so to speak.