Donald Trump’s plan to drill for oil in the Arctic wilderness is dividing Indigenous Alaskans

The Inupiat community of Alaska have hunted bowhead whales for generations

Dressed in a wolf-head hat and a coat lined with squirrel pelts, Marie Rexford is fermenting whale meat in the small village of Kaktovik on the north-eastern shores of Alaska.

The meat sustains the Indigenous Inupiat community through the winter months. But in summer, it attracts some unwelcome visitors to town.

“We’ve got a lot of whale meat in the village and they’re smelling it … they want to get at it,” she says of the polar bears that wander into the village with increasing frequency.

The sea ice that once came all the way up to the shore of their village on the edge of the Beaufort Sea — even in the summer — is now hundreds of kilometres away. It’s bringing hungry bears in closer.

“There’s no way to get their seal right now,” Marie says. “They got no ice to hunt seal.”

There are an estimated 26,000 polar bears left in the wild and scientists say they could be extinct in Alaska by 2050. That’s of no concern to Marie, however, who’s lived with the bears all her life.

A polar bear walks along the edge of the water.

Polar bears are coming into Kaktovik more frequently as their hunting grounds recede with the melting ice.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: NIALL LENIHAN

“They’re a nuisance for me. They get my good food,” she says, adding, “they’re not endangered to us”.

For Marie and many in the Inupiat community, the fight for survival is more pressing than protecting the environment right now.

Although surveys have shown the community is divided, Inupiat leaders have given their support to a plan to explore for oil in their own backyard — even as other Indigenous Alaskan communities are opposing the move.

Oilfields among the ice beds

Some 200 kilometres from Kaktovik is Prudhoe Bay, home to the most productive oilfield in the United States. At its peak, the site produced nearly 2 million barrels of oil per day, driving Alaska’s economy and powering the lower 48 states.

The oil is fed to the mainland by the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Over 1,000 km long, the pipeline transports the oil from north to south Alaska across three mountain ranges and 500 rivers and streams.

Reporter Zoe Daniel stands in front of a silver pipe.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline pumps oil 1,000 kilometres across the US state. ABC reporter Zoe Daniel stands next to a section of the pipe.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

These days, the Prudhoe Bay field is running low and the Trump administration is looking elsewhere for supplies. It wants to explore for oil and gas in the nearby Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a wilderness that’s been protected for decades.

The Inupiat are the traditional owners of the land where the drilling is planned and they’ve voted to support the proposal. Initially against it, Marie has reconsidered.

“When I first heard about it, I didn’t like it at all,” she says.

“But after listening to the elders on what they had to go through, I saw the opportunities — what it can do for our young kids.”

Traditional hunters and gatherers, the Inupiat have lived along Alaska’s Arctic coastline for thousands of years.

“Sheep, whale, ducks, seal, fish, ptarmigans — we live off the land,” she says. “It’s better food than store-bought, I think. I notice when I have store-bought food, I get hungry faster and colder faster.”

At this time of year, the Inupiat have a quota to harvest three Bowhead whales which will feed their small community of about 250 through the winter. Now 56 years old, Marie learned the skills and rituals of whale hunting when she was a girl.

“It is very important. We need to have this food to survive up here, to stand the cold.”

A sign reads ‘Kaktovic’ and shows three polar bears.

More and more tourists are coming to Kaktovic to see polar bears up close.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

Marie’s village of Kaktovik is hemmed in by the vast coastal plain of the ANWR on one side and the ocean on the other. After a long-running push by conservationists that began in the 1950s, more than 19 million acres of land was formally declared a refuge in 1980, making it America’s largest protected wilderness.

However, the US Congress left open the possibility of exploring for oil within a 1.5-million-acre piece of the refuge, known as the “1002”.

The Inupiat remain furious they weren’t included in the process that led to the protection of the Arctic Refuge lands. They say it ultimately restricted their access to some of their hunting grounds.

This time around, if oil is found and drilling goes ahead, the Inupiat stand to gain a windfall in tax revenues to fund much-needed infrastructure, such as roads and sewerage. It’s for these economic reasons the Inupiat support the drilling.

America’s last great wilderness

An aerial shot of an Alaskan wildlife refuge during the day

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is the largest protected wilderness in the United States.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

To visit the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the “1002” area, where oil exploration is planned, the only way in is by air. The weather’s been windy, even gale force, delaying our trip, but today the valley is bathed in bright, warm sunshine with barely a breeze. Our pilot, Kirk Sweetsir, takes us over the vast Brooks Range, the highest peaks in the Arctic Circle.

“You have to be ready to go whenever it allows you. There can be days on end where it’s just inaccessible, fogged in and horrible,” he says as we glide through temporarily blue skies. “Today is just the day that you dream for.”

Down below, the trails of thousands of Porcupine caribou on the sheer slopes are so close it’s as if you could reach out and trace them. Caribou cover thousands of kilometres in their annual migration through Alaska and Canada.

Travelling with us is retired biologist and conservationist Fran Mauer, who spent much of his career working in the Arctic Refuge for the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Zoe Daniel pictured with mountains outside the plane window.

The protected areas of Alaska’s “1002” wilderness area are only accessible by flying over the Brooks Range.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

“If you look down right below us … there’s just a continuous network of trails all through this area here,” he says.

A prehistoric-looking musk ox stands on a grassy slope and two grizzly bears ramble together nearby. Then there are the caribou: hundreds, perhaps thousands, dotted across the valleys.

The Arctic Refuge is not a national park. It has no roads, no marked trails and no developed campsites. It was preserved to allow the wilderness to exist here undisturbed. There are few visitors — the odd hunter and hiker who arrive by air and the occasional film crew.

“In north-east Alaska, the Brooks Range arches up close to the Arctic Ocean allowing for a compression of ecological zones that you cannot find elsewhere in Alaska in such a small area,” Fran Mauer says. “It’s the proximity of these eco-zones together that enhance its values.”

“We’ve been fortunate that it’s been preserved for the American people for nearly 60 years now. And we hope it will be this way 500 years from now,” he says, his voice full of emotion.

But perhaps not.

The politics of oil

The refuge’s coastal plain is an icy tundra covered in sensitive lichen vegetation. It is also the calving grounds for the Porcupine caribou.

A single exploratory well drilled here in the 1980s apparently returned meagre results but the oil companies won’t release the details. Since then, Republicans have held on to the hope of further exploration.

A river winds through a wide tundra with mountains in the distance.

Within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is an area called the “1002”. It’s a caribou calving ground and possible site for oil exploration.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

President Donald Trump welcomes the prospect of accomplishing here what others have not. In a speech addressing fellow Republicans in early 2018, Trump described the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as “one of the great potential fields anywhere in the world”.

“I really didn’t care about it and then when I heard that everybody wanted it — for 40 years they’ve been trying to get it approved — I said, ‘Make sure you don’t lose ANWR!'” Trump said.

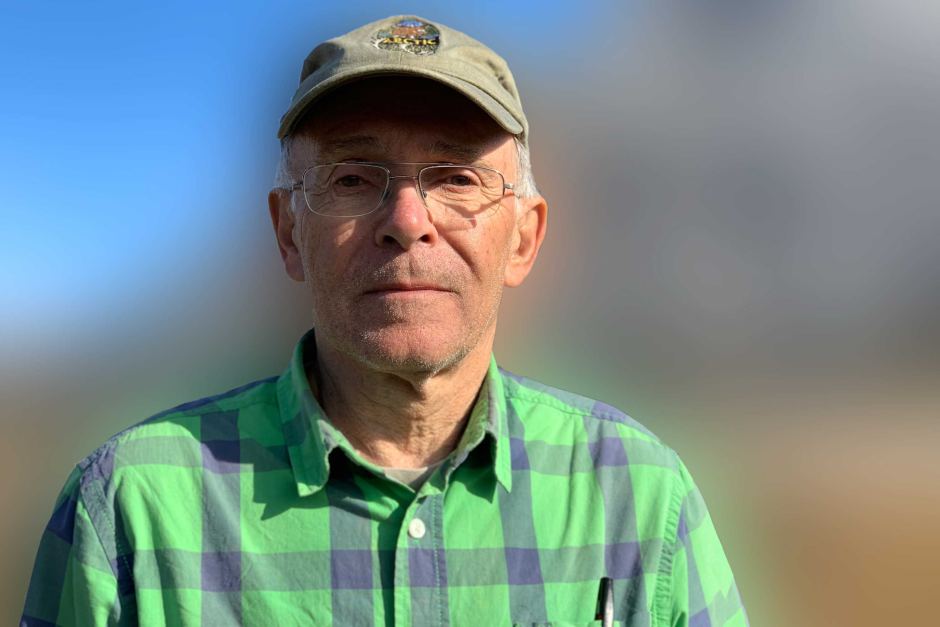

Fran Mauer poses for a picture.

Retired biologist Fran Mauer says it’s a critical time for the US to protect an untouched wilderness.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

Congress passed the drilling proposal in 2017. Since then, it’s been subject to an accelerated environmental impact process, to allow for the sale of land leases in the refuge. Several scientists who contributed to this environmental process claim their evidence was skewed to allow for speedy approval.

“In my opinion, the rush is to sell leases before there’s another election, it’s as simple as that,” Fran Mauer says.

Polls have shown that up to 70 per cent of Americans are against drilling in the ANWR.

“They know that the American people ultimately do not want this and they’re trying to push it through while they have the votes and the power in the White House to do it,” says Fran Mauer.

“It’s a crime. The American people are being robbed.”

The sacred place where life begins

Sarah James sits in front of a pile of butchered caribou.

Gwich’in elder Sarah James prepares caribou meat using an age-old process. She opposes drilling in the caribou calving grounds.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

In Arctic Village, just outside the refuge boundary, 75-year-old Gwich’in elder Sarah James is busy cutting and smoking caribou meat as winter looms. The Porcupine caribou have been central to the subsistence lives led by the Gwich’in for millennia.

“The caribou is good for our body and we can’t go without it,” Sarah tells me, hanging strips of meat on wooden railings over a smoky fire in a small shed. “It takes a certain hunger away and that’s the way it is with us.”

The Gwich’in tribe is made up of 15 communities across Alaska and Canada. They’re mostly isolated settlements and are reliant on hunting and fishing. For them, the coastal plain of the ANWR is “the sacred place where life begins”. It’s where the caribou give birth to their young.

“Human is an enemy for them. So, there’s no footprint up there, no enemy. We want to keep it that way,” Sarah says.

Sarah is a long-time community advocate against any development in the refuge. She’s worried that oil drilling will disrupt the caribou migration.

“It’s always been my way of life,” she says. “Protect the caribou.”

A man drives a quadbike with butchered caribou on the front.

Gwich’in hunters return to Arctic Village after a successful caribou hunt.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: MATT DAVIS

The Gwich’in are determined to preserve their culture and traditions for future generations.

It’s a cold, clear evening when Foreign Correspondent heads out on a caribou hunt with a group of young men, who began hunting as boys. The group speeds up a mountain road on quadbikes in the last light of the day, rifles slung over shoulders. From above the tree line, Arctic Village is a tiny collection of houses nestled in the bend of the snaking river which forms the refuge boundary. The massive Brooks Range looms to the north.

The hunters shoot a young bull, butchering the caribou on the darkening mountainside. They pride themselves in using every part of the animal and sharing the meat throughout the community.

“This is the way we were taught, the way we practice, the way we pass on our teachings … Nothing goes to waste up here,” says Jerrald John, who’s been hunting here for 25 years.

When the meat is brought back to the village, Sarah James continues the age-old process of cutting and preserving.

“We depend on our food as a way of life, of who we are, and it’s Gwich’in,” she says.

Over the years, Sarah has represented her community in Washington DC and appeared before the United Nations in New York speaking out against recurring oil drilling proposals.

“We’re pretty united on this as a family and as a whole Gwich’in nation,” she says. “We haven’t changed our mind.”

A critical moment

Pine trees line a hill next to a river with mountains in the distance.

Polls have shown up to 70 per cent of Americans oppose drilling in the ANWR, but a push by the current White House could see exploration leases sold later this year.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: NIALL LENIHAN

Leases for exploratory drilling on the coastal plain could be sold by the end of the year and several small Australian companies may be among the bidders.

For retired biologist Fran Mauer, it’s a critical moment.

“If we degrade what’s here, the way it is now, it’s a great loss to all of mankind because we have so few places left that are like this,” he says.

Marie Rexford hesitates in her support for drilling when considering the concerns of the Gwich’in.

“They’re thinking of their caribou. I don’t blame them,” she says.

“But they say it’s going to happen anyway. Everything’s changing anyway. We’ve got to adapt to the new changes.”

Tourists on a boat observe a polar bear and two cubs.

Kaktovic has seen growing tourist numbers thanks to polar bears but some villagers say oil drilling could bring more opportunities for the future.

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT: NATE SONDERMAN

After fighting the same battle over and over for decades, Sarah James remains resolute.

“We are going to win because this is the right thing to do. Everybody knows that.”