Enemies Of India Tried Their Best To Decimate Indian Space Progress Destroyed A Brilliant Scientist : All Need To Be Punished To Hell

This is the story of a super conspiracy , hatched somewhere ex India to destabilize the rapid progress being made by India in the final frontier of SPACE . Worried that India will soon be surpassing in this field the conspiracy aimed at a few top scientists dealing with the cryogenic fuel and engines in the ISRO . Minions of the Government of Kerala were the conduits used for this dastardly act.

Finally most of the culprits have been identified, the Scientists have been compensated monetarily and even honoured. However the culprits are still scot free . They need to be punished and punished most severely by the Government of India .

Time line of the case :

1994 – Narayanan arrested and remanded in custody, then bailed in January 1995

1996 – Exonerated by the Central Bureau of Investigation

1998 – Supreme Court finally dismisses Kerala government’s appeal

2001 – Kerala government ordered to pay compensation

2018 – Supreme Court orders investigation into fabrication of case

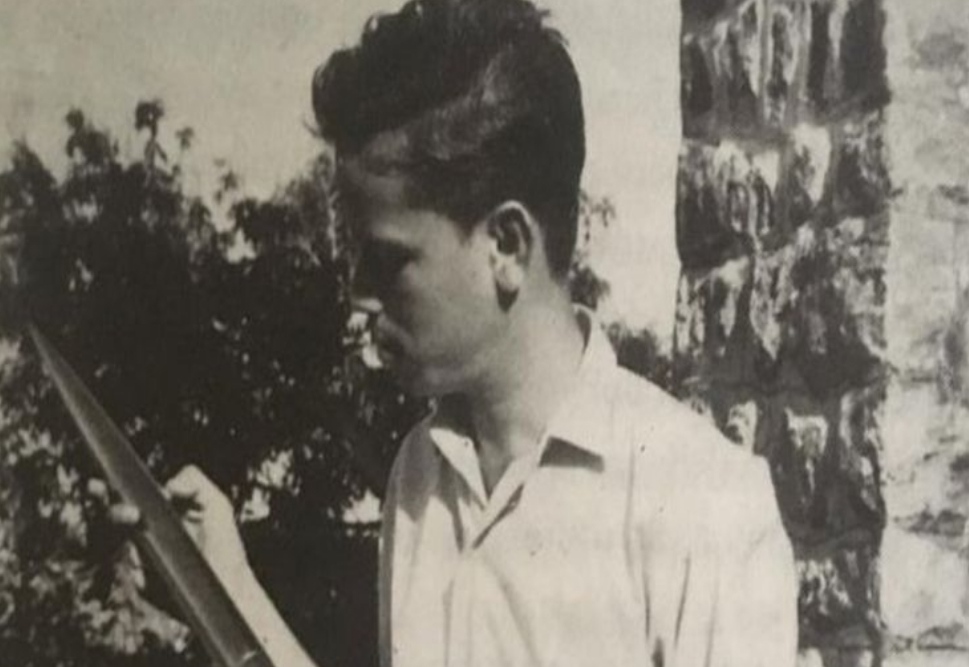

Nambi Narayanan was the first boy in a middle-class family, after five girls. His father was a businessman, trading in coconut kernel and fibre. His mother stayed at home to look after the children.

Young Nambi was a good student and topped his senior class. He went to an engineering school, got a degree and worked in a sugar factory for a while, before joining the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro). “I always had a fascination for aircrafts and flying objects,” he says.

At the agency, he rose rapidly through the ranks until he won a scholarship to study rocket propulsion systems at Princeton University. He rejoined the space agency when he returned home, three years later.

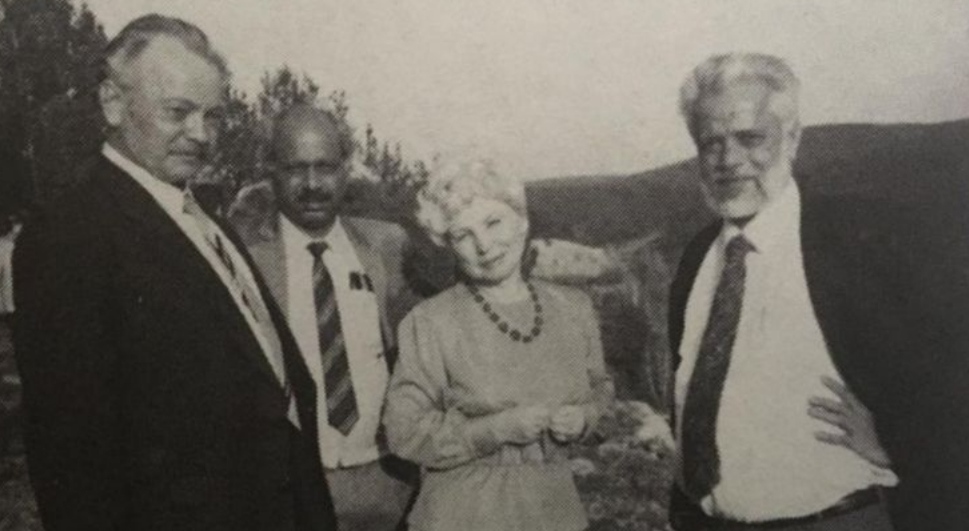

At ISRO Mr Narayanan worked with the stalwarts of India’s space programme: scientists like Vikram Sarabhai, its founder and first chairman, Satish Dhawan, his successor, and Abdul Kalam, who later became India’s 11th president.

“When I began working with Isro, the space organisation was in its infancy. We never really had a plan of developing any rocket systems. We were planning to use rockets from the US and France to fly our payloads,” Mr Narayanan says.

But the plan changed, and Mr Narayanan became a key figure in the project to develop homegrown Indian rockets right) with Russian scientists in the early 1990s

He worked diligently as a scientist until his life was turned upside down in November 1994.

One winter afternoon a quarter of a century ago three policemen arrived at a house in a narrow lane in the southern Indian city of Trivandrum, the capital of the state of Kerala. The officers were polite and respectful, Nambi Narayanan remembers.

They told the space scientist that their boss, a deputy inspector general of police, wanted to talk to him.

“Am I under arrest?” Mr Narayanan asked.

“No sir,” the officer said.

It was 30 November 1994. The 53-year-old scientist led the Indian space agency’s cryogenic rocket engine project, and was responsible for acquiring the technology from Russia.

Mr Narayanan walked out to the waiting police vehicle. He asked whether he should sit in the front or the back – suspects were usually dumped in the back seat.

The policemen asked him to sit in the front, and the Jeep rolled out of the lane.

When they arrived at the police station, the boss wasn’t there, so Mr Narayanan was asked to wait on a bench. Policemen gaped at him as they passed by.

“They had that look as if they were looking at someone who had done some crime,” Mr Narayanan says.

He waited and waited. The boss didn’t turn up.

As night fell, he dozed off on the bench. When he woke up next morning, he was told he was under arrest.

A scrum of journalists had arrived, and within hours newspapers were describing him as a traitor – a man who had sold rocket technology to Pakistan, after falling into a honey trap set by two women from the Maldives.

His life was never the same again.

A month before his arrest, the Kerala police had arrested a Maldivian woman, Mariam Rasheeda, on charges of overstaying her visa. Weeks later, they picked up her friend, Fauziyya Hassan, a bank worker visiting from Male, the capital of the Maldives. A major scandal then erupted.

Inspired by police leaks, local newspapers reported that the Maldivian women were spies stealing India’s rocket “secrets” and selling them to Pakistan, in cahoots with scientists at the space agency.

Mr Narayanan, it was now claimed, was one of the scientists who had succumbed to the women’s charms.

The day he was formally arrested, Mr Narayanan was produced in court.

“The judge asked me whether I would confess to the crime. I asked, ‘What crime?’ They said, ‘The fact that you have transferred the technology.’ I couldn’t understand anything,” he remembers.

The judge remanded him to judicial custody for 11 days. A memorable image from that time shows the scientist walking down the steps of the court building, dressed in a dark-coloured shirt and light grey trousers, surrounded by policemen.

“I was in a shock, and then a trance. At one instance it appeared to me that I was watching a movie – with me as the central character,” Mr Narayanan wrote in his memoirs.

yanan says India’s rocket project suffered because of the scandal

Over the next few months, his dignity and reputation were torn to shreds. He was charged with violating India’s official secrets law and corruption, among other things.

His interrogators beat him up and handcuffed him to a bed. They forced him to stand and answer questions for 30 hours on end. They made him take lie-detector tests even though the results are not admitted as evidence in Indian courts.

Then they took him to a high security prison, where one of his co-prisoners was a “serial killer” who had bludgeoned his victims to death. (The man told Mr Narayanan that he had been reading about the case and that could tell that the scientists were innocent.)

Mr Narayanan told the police that rocket secrets “could not be transferred by paper” and that he was clearly being framed. The fact that India was still struggling to obtain cryogenic technology to make powerful rocket engines didn’t cut any ice with the detectives.

In the end, Mr Narayanan spent 50 days in captivity – including nearly a month in prison. Whenever he was taken to a court hearing, crowds appeared shouting that he was a spy and a traitor.

But a month after his arrest India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) took over the case from Kerala’s Intelligence Bureau. Mr Narayanan told federal detectives that none of the information he dealt with was classified. “I don’t know how this whole thing has come to this stage. We are terribly sorry,” one detective told him.

After finally securing bail on 19 January 1995, he arrived home shortly before midnight.

He went upstairs to break the news to his wife. She was sleeping on the floor in a dark room, and responded only after he called out her name twice.

“She turned around slowly, raised her head and stayed still, staring into my eyes. She had a strange expression, as if she was watching me doing something horrible,” Mr Narayanan recounted later.

“Then she let out a shriek that I had never heard – from a human or an animal.”

The cry coursed through the house. Then she fell silent.

Her husband’s incarceration and absence had severely affected Meenakshi Ammal’s mental health. The couple had been married for nearly three decades and had brought up two children together, but after Mr Narayanan’s arrest the austere temple-going woman had slipped into depression and stopped talking.

Apart from Mr Narayanan, five others had also been accused of espionage and transferring rocket technology to Pakistan. One was his colleague at ISRO, D Sasikumaram; there was also Ms Rasheeda and her friend (neither of whom Mr Narayanan had met, before he was arrested); and two other Indian men, an employee of the Russian space agency and a contractor.

In 1996, the CBI’s final 104-page report exonerated all of them. Federal detectives said there was no evidence of any confidential documents being stolen from the space agency and sold, or of money being exchanged for drawings of engines. An internal investigation by Isro also found that no drawings of the cryogenic engines were missing.

Mr Narayanan went back to work for Isro – though now in an admin role in Bangalore – but his travails hadn’t come to an end. Even after the detectives closed the case, the local government tried to reopen it, and dragged in the Supreme Court, which finally dismissed the case in 1998.

When Mr Narayanan sued the Kerala government for framing him, he was awarded five million rupees ($70,000; £53,000). Last month, the government said it would pay him an additional 13 million rupees as compensation for his illegal arrest and harassment.

But from the 78-year-old’s point of view, the story is not finished yet. In 2018, the Supreme Court ordered an investigation into the role of the Kerala police in the fabrication of the case against him, and Mr Narayanan is keen to see the results.

“I want people who fabricated this case against me to be punished,” he says. “One chapter is over, but the next chapter is still there.”

The motive for the plot against him and the five others remains a mystery. Was it a conspiracy by a rival space power – as Mr Narayanan suspects – to scuttle India’s development cryogenic rocket technology, which eventually became the backbone of the country’s successes in space? Did it have to do with rivals who were nervous about India forcing its way into the commercial satellite launch market with competitive prices? Or was it purely a product of corruption with India itself?

“It was born out of one conspiracy. But the conspirators were different with different motives, and the victims were the same set of people,” says Mr Narayanan.

“Whatever it is, my career, honour, dignity and happiness were lost. And the people who were responsible for this are still scot free.”