“If You Have A Strong Heart…”: China Tycoon’s Turnaround After Jail

In the period since his release — in 2013, after serving a reduced sentence — Zhang Wenzhong has made Wumart a player in China’s hyper-competitive supermarket sector again.

Customers use self check-out kiosks inside a Wumart supermarket in Beijing.

In 2018, Zhang Wenzhong was cleared by China’s top court of financial misconduct charges after earlier spending more than half a decade in prison. Three years later, the Chinese tycoon has revived the supermarket business he founded, and is about to launch two initial public offerings — one in Hong Kong and the other in the U.S.

It’s a marked reversal of fortunes for Zhang, 59, who watched the Wumart grocery store chain he started in 1994 languish after he was convicted of fraudulently receiving funds from the state, bribery related to a business he had tried to acquire, and using funds from an insurance firm to trade for personal gain.

While the convictions were eventually overturned by China’s highest court in 2018, Zhang returned from prison to a company that had been deserted by its staff, suppliers and investors.

“This experience let me really understand life is short,” Zhang said in an interview with Bloomberg Television. “Everything can suddenly happen to you. In the meantime, everything will just pass.”

In the period since his release — in 2013, after serving a reduced sentence — Zhang has made Wumart a player in China’s hyper-competitive supermarket sector again.

He did it by pivoting Wumart stores, known as Wumei in Mandarin, in the direction of innovations that tech giants like Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and JD.com Inc. pioneered in China’s $1.3 trillion groceries market. These included guaranteeing rapid delivery of fresh groceries, and giving customers the option to bypass check-out counters and pay via mobile phones.

Wumart has used its offline supply chain advantages to launch sub-brands selling fish and vegetables good only for a day, while it now delivers to 94% of Beijing compounds within the fifth ring road in as fast as 30 minutes, with its hypermarkets serving as fulfillment centers.

Zhang also fought to build scale, borrowing to buy majority stakes in the China businesses of British home-improvement chain B&Q Ltd. and German wholesaler Metro AG.

Now, he’s looking to raise as much as $1 billion in an IPO in Hong Kong for WM Tech Corp., a unit that includes the company’s two flagship chains — Wumart, with 426 stores, and Metro China, which has 97.

WM Tech’s prospectus shows its revenue jumped to 39.1 billion yuan ($6.1 billion) in 2020, up from 21.4 billion yuan in 2018, largely due to the Metro acquisition. On its own, the Wumart chain’s revenue grew 6.4% and 8.1% in 2019 and 2020 respectively, according to the documents.

Separately, Zhang also founded an e-commerce platform named Dmall Inc. that provides online retail solutions, helping traditional brick-and-mortar businesses bring their services online via its cloud and operating systems.

Dmall, backed by investors like Tencent Holdings Ltd., IDG Capital and Lenovo Group Ltd.’s technology industry fund, is planning to list in the U.S. as soon as the second half of this year, Bloomberg earlier reported.

Still, Zhang faces an uphill battle to keep his businesses growing in China’s fragmented, competitive groceries industry.

Workers handle produce prior to packaging inside Wumei Technology Group Inc.’s Wumart food processing center in Beijing, China, on June 4, 2021.

Wumart had a 3.4% share of China’s hypermarket industry in 2020 according to data from Euromonitor International, making it the sixth-largest chain. While that’s an improvement from 2015’s 2%, it’s still far behind the 9.3% share enjoyed by Walmart Inc.’s China operations, Yonghui Superstores Co. at 11.9% and the Alibaba-backed Sun Art Retail Group, which leads with a 13.7% share.

And while Wumart has managed to catch up in some areas, China’s supermarket landscape continues to change rapidly, driven by efforts to provide shoppers with a seamless off and online shopping experience centered on mobile apps, especially as more consumers abandon physical retail in the wake of the pandemic.

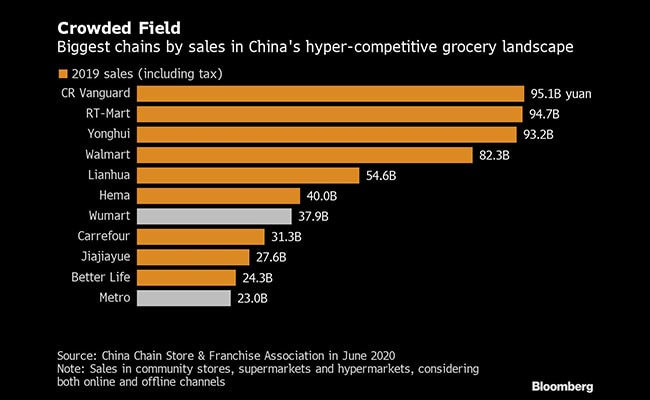

Tech giants have the advantage here, with their existing digital infrastructure and control of customer data. Alibaba’s Hema supermarket chain started only in 2015 and already makes more revenue than Wumart’s network, according to 2019 data from China Chain Store & Franchise Association. Alibaba also controls market leader Sun Art and has a 20% stake in Suning.com.

Competition is also fierce because there are no clear market leaders: combined market share of the five largest grocery retailers in China is only 27%, compared with 66% in the U.S., 76% in the U.K. and 77% in France, according to Lingyi Zhao, the Beijing-based chief retail and e-commerce analyst at SWS Research, citing data aggregated from consumer research company Kantar.

“Supermarkets had long been a thin-margin business that people say is like picking up coins on the ground,” Zhao said. “Now with tech giants entering the battleground, it adds a new source of pressure.”

WM Tech is highly indebted after borrowing to fund its turnaround, which makes the timing of the IPOs crucial. Its liabilities-to-assets ratio was 97% in 2020, compared with just over 60% for bigger industry rivals like Sun Art and Yonghui.

Liabilities have ballooned to 40.8 billion yuan ($6.4 billion) due to the acquisitions, while finance costs increased 33% to 760 million yuan in 2020 from the previous year — higher than WM Tech’s net income in the same period.

Zhang says the company is keeping up with trends in the Chinese industry and investing into new growth drivers, like services for “community buying,” in which groups form on social media to place grocery orders in bulk for neighbors and friends. In March, the company agreed to invest in Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing Inc.’s community group buying service, entering a space that tech companies like Meituan and Pinduoduo Inc. have put money into.

Wumart also began livestreaming sales events last year and now typically holds them twice a week, co-hosted by different brands.

“Today, Wumart stores are very different from six years ago,” Zhang said. “The world has been changed. If you want to survive, as retailers you need to adapt.”

Workers put product stickers on packaged mushroom in Wumart’s food processing center in Beijing, China on June 4, 2021.

Initially handed an 18-year sentence on the fraud, organizational bribery and embezzlement charges, Zhang was released in 2013 after his sentence was shortened. He then spent years grappling with China’s legal system before the Supreme People’s Court overturned the convictions against him in 2018.

In its decision, the court said private companies had been eligible for state funds at the time Wumart applied, that Zhang’s company hadn’t had an improper advantage in the acquisition, and that there was no evidence Zhang had embezzled funds for his own benefit.

Whether this history has an impact on his fundraising abilities remains to be seen. Dmall’s U.S. listing is being planned at a time when scrutiny of Chinese business by the Biden administration is increasing.

Drawing on his prison time, Zhang struck a sanguine note on the challenges ahead.

“If you really have a strong heart, if you really survive from those kinds of hardships, you will become stronger,” he said. “You can survive in different seasons.”

–With assistance from Dong Cao, Daniela Wei, Coco Liu and Venus Feng.