Afghan Snowfinch: Memories of a birdwatching journey fifty years ago

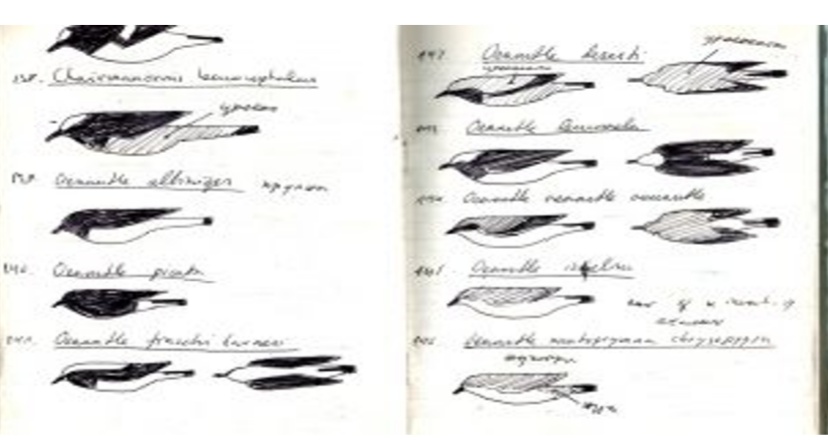

Drawings of mynahs by Serbian ornithologist Voislav Vasić, who travelled to Afghanistan in 1972 in search of birds. Photo: Author

The bearded vulture, the rich diversity of wheatears and, above all, the Afghan snowfinch – found nowhere else in the world – are what drew a young ornithologist, Voislav Vasić, to travel from Yugoslavia to Afghanistan in the summer of 1972.

In this guest dispatch, Vasić, now the retired head of the national Natural History Museum in Belgrade,* recalls his journeys in search of birds, by bus, truck, taxi, jeep, as well as on a bicycle, horse and camel through almost all parts of Afghanistan. He recalls the birds he saw, the actor-friend he made and the ornithological scandal he heard about.

Why Afghanistan?

Ever since AAN published a dispatch on the lizards of Afghanistan based on a collection of lizards I brought back from Afghanistan to Europe in 1972, I have felt the need to write about the main purpose of that journey – to discover more about the birds of Afghanistan.

I also wanted to share some recollections about my journey, which was in itself highly unusual. The ‘hippy trail’ through Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India was well-trodden by youngsters from western Europe in those years, but few from Tito’s Yugoslavia made that journey.

Moreover, I was not a hippy. I was a naturalist driven to head east by a desire to see the particular and very special birds of Afghanistan. I knew there would be exciting birds, but in 1972, there was no pocket field guide with illustrations of the birds of Afghanistan or the region.

At the time, I was passionately interested in ‘zoogeography’, the branch of zoology that deals with the geographical distribution of animals. I had graduated in biology from the University of Belgrade in 1967 and was working at the Institute for Biological Research, Siniša Stanković.

I thought that traveling from the Bosporus to the heart of Asia would give me a great opportunity to get to know and truly understand the wildlife of ‘real’ steppe and desert. Up until then, I had only encountered its miserable and modified fragments in the Balkan Peninsula.

In addition, although I had climbed almost all the highest mountain peaks in Yugoslavia, my mountain climbing record was Triglav peak in Slovenia, barely 2,870 metres high. In Afghanistan, the Hindu Kush, which averages an altitude of 4,500 metres, was awaiting me.

My choice of destination was greatly influenced by the emergence of a remarkable book – a handbook on the birds of the Middle East, “Les Oiseaux du Proche et du Moyen Orient” by two famous French researchers, François Hüe and Robert Daniel Etchécopar, with incredibly good illustrations by Paul Barruel.

It encompassed Afghanistan, but only to a certain extent. This book inspired me to see what more I could find in this, for bird-lovers, under-researched country. There was more, of course.

My classical secondary education meant the idea of visiting cities founded by Alexander the Great, which still lay scattered like a strange constellation, and the prospect of being in the presence of the great Greco-Buddhist monuments only fed my curiosity to travel more.

My decision to embark on this rather uncertain zoological exploration was buoyed up my having just finished my year-long national service in the Yugoslav People’s Army. I felt strong and confident.

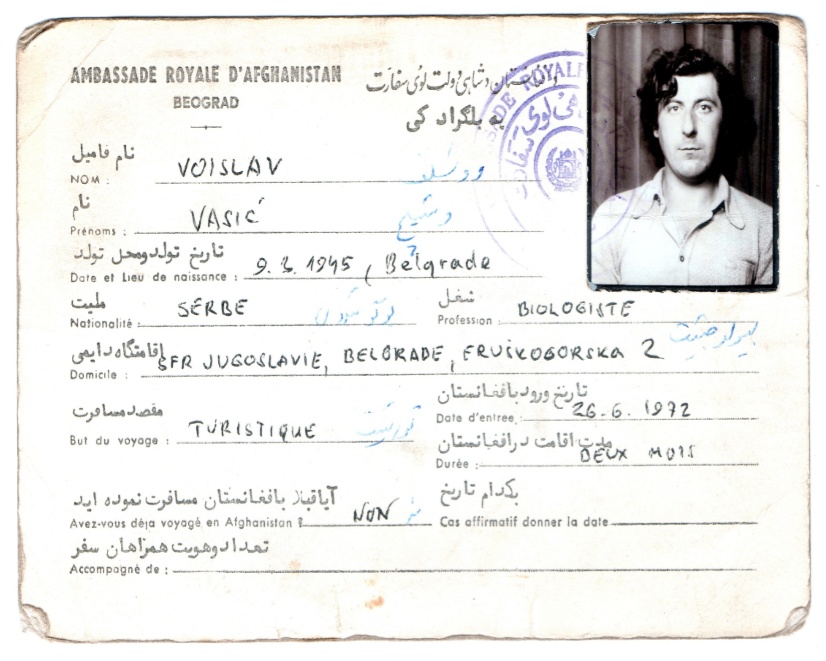

Voislav’s visa, issued in Belgrade, 1972. Photo: Author

Three great expectations

Of my many ornithological ‘great expectations’, I will name just three – and how I came to see them all in Afghanistan.

Third-ranking was my desire to observe spectacular birds of prey, above all, the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), also known as the Lammergeier, which I had only seen once before in Macedonia, the most southerly of the six republics then making up Yugoslavia. Even 50 years ago, such large predators had already become rarities in most of Europe.

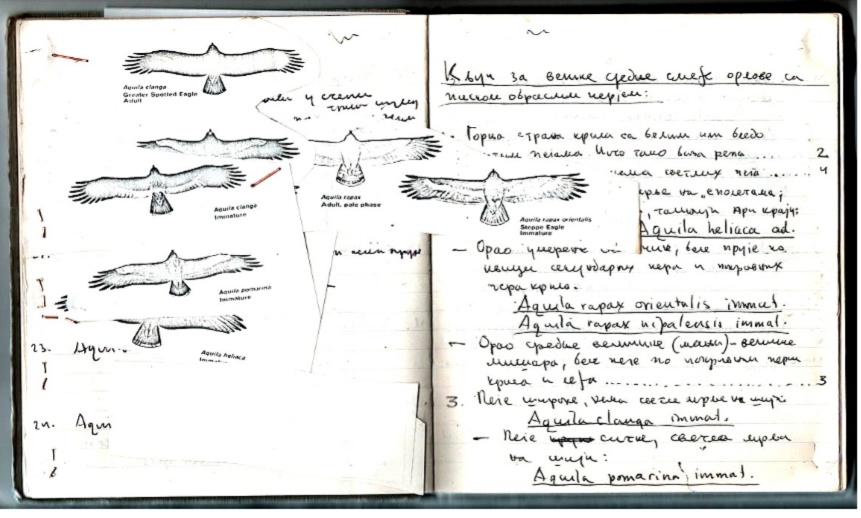

In Afghanistan, on the contrary, I was to encounter a few more species of eagles and falcons that I had never seen before. Before setting out, I carefully wrote notes and glued thumbnail pictures of the raptors I hoped to see into one of my two field notebooks (the grey notebook).

Afghanistan was to be full of ornithological surprises and I was certainly not disappointed by the raptors. After the Egyptian Vulture, the Lammergeier was the most common type of vulture throughout Afghanistan, and was especially common in the central mountainous areas, where I saw it daily. It was somewhat less frequent in the lower parts in the districts of Qala-ye Naw and Bala Murghab of Badghis province.

By any measure, the Lammergeier is a huge, amazing bird that feeds almost exclusively on the marrow bones of dead animals. It is attracted to carcasses that have been previously gnawed away at by jackals and feathered scavengers.

However, the most abundant vulture in Afghanistan was the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), which was found especially around villages and nomad camps, as it feeds on the worst kinds of waste.

Once, in the Dara-ye Ajdahar, the Dragon Valley in Bamyan, two men suddenly appeared before me with rifles and one freshly-killed Egyptian Vulture. They offered it to me to buy. They mimed and gestured to say that it would taste great when cooked.

I instantly recalled the street urchins in Kabul who had gathered around me as around any other stranger, mocking me with: “Mister Kachaloo, Mister Kachaloo!” (Mr Potato), for reasons I could never discern. Likewise, I believe these vulture murderers also thought strangers were completely ignorant and worthy of any sort of deceit. (1)

The vultures Voislav hoped to see in Afghanistan as seen in his Grey Notebook. Photo: Author

My second great desire was to get acquainted with as many as possible of the species of wheatears of the genus Oenanthe.

Central Asia is the centre of diversity of these largely desert-steppe dwelling passerines (ie birds with claws adapted for perching) with their characteristic white rumps.

Every wheatear species looks similar to at least one other and it is especially difficult to identify females and youngsters in their transitional seasonal plumages.

I was to encounter this problem throughout Afghanistan. I had to deal with an extraordinarily wealth of varieties of wheatear and cope with the serious problem of how to reliably identify them without a guidebook.

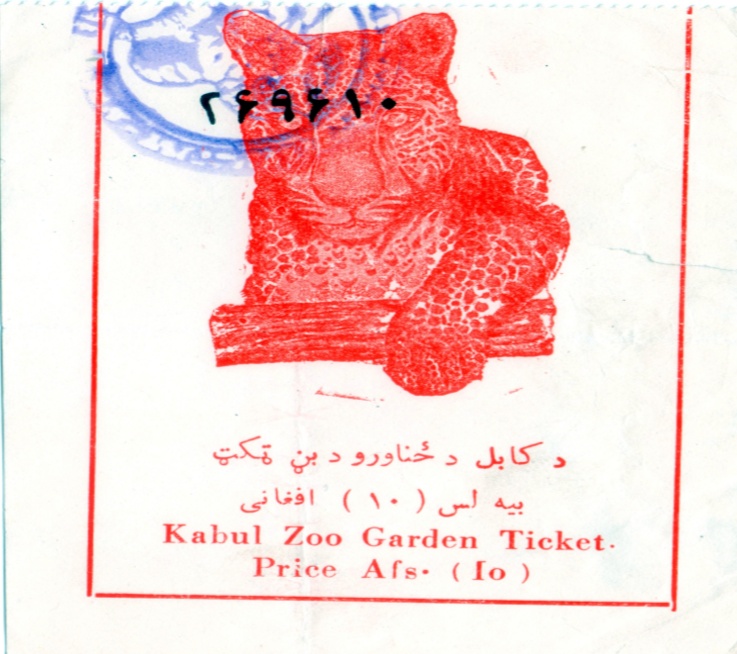

That is why as soon as I got to Kabul (overland from Herat), I went to the Kabul Zoo that then and now hosted a small zoological museum. It was founded by the German zoologist Jochen Niethammer, son of the even more famous Günther Niethammer, the curator-zoologist of the Berlin, Bonn and Vienna Natural History Museums.

Niethammer Jr was in Kabul from 1964 to 1966 as part of collaborative programme between Bonn and Kabul Universities, where he studied mammals and birds. (2) At that time, the museum had a collection of birds whose specimens had been identified personally by Niethammer Jr.

When I got there, the zoo and museum were being run by two other German zoologists, Günther Nogge (assistant professor at the Kabul University and later long-time director of the Cologne Zoo, author of “Afghanistan, Zoologically Considered”) (3) and M Bokler (about whom I know nothing), to whom I had previously announced myself by a letter. They welcomed me in and allowed me to inspect the entire collection of birds in detail and to use the museum’s library.

A ticket to the Zoo. Photo: Author

For two weeks, I studied the stuffed birds of Afghanistan held by the museum and learned how to identify the living ones in the field.

I recorded all of the information in the first of my two notebooks, the grey one, from which I was never parted. My companion for those weeks was an orphaned chimpanzee who, while I was studying birds, sat on my lap, embracing me tightly with her long arms.

Thanks to that self-study at the Kabul zoo and the museum in July 1972, I was able to identify as many as eight different species of wheatear in the field.

That might sound easy, but those eight species appeared to me in at least twenty different ‘morphs’, ie having different physical features, such as variations in colour and pattern of plumage, but belonging to the same species.

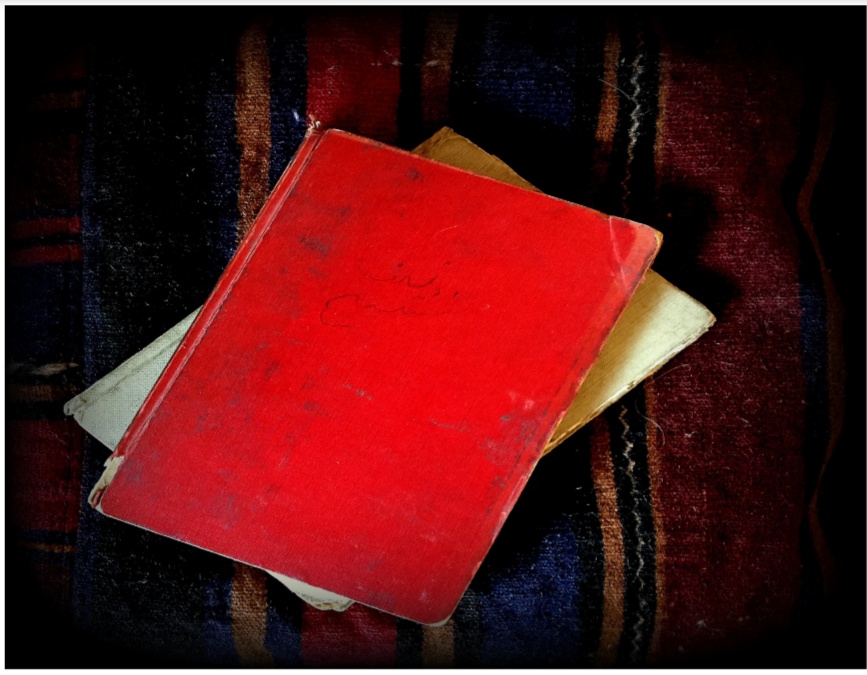

Voislav’s grey and red notebooks. Photo: Author

Finally, the third and most important reason for me visiting Afghanistan was my desire to see the Afghan snowfinch (Pyrgilauda theresae), a species endemic to Afghanistan.

I should say here that birds fly long distances with ease so, compared to animals and plants, bird species whose overall distribution remains within the borders of one country, particularly one as small as Afghanistan, are rare.

This is true unless the country is an island when the barrier of the ocean encourages distinctive evolution. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Afghan snowfinch is the only endemic Afghan bird.

However, Afghanistan is a place where two biogeographical regions meet, regions known to biologists as the Palearctic, which stretches across all of Europe and Asia north of the foothills of the Himalayas, as well as North Africa and the northern and central parts of the Arabian Peninsula, and the Indomalaya, which extends across most of south and southeast Asia and into the southern parts of East Asia. It Is such places that biodiversity is born. (4)

About the Afghan snowfinch and a wicked historical, ornithological scandal

The Afghan snowfinch is a grey-brown passerine bird that lives in the mountains about 3,000 meters above sea level. Despite its standard English name, it is not a finch but a species that belongs to the sparrow family, the Passeridae.

It is very similar to the White-winged snowfinch (Montifringilla nivalis), which lives in the summer snow zone of the high mountains of southern Europe (Pyrenees, Alps, Apennines, Balkan Mountains), as well as in Afghanistan.

Perhaps a better alternative name in English would be the Afghan ground-sparrow, since the most striking feature of this species is the way it nests in the burrows of rodents, most commonly, ground squirrels.

As it makes its nest of hairs and feathers deep underground, at the end of the tunnel farthest from entrance, we can really consider it a subterranean sparrow.

For science, the Afghan snowfinch was a relatively late discovery. It was identified in 1937, on the Shibar Pass between Kabul and Bamyan, and described under the name Montifringilla theresae that same year by a British army colonel, Richard Meinertzhagen (1878–1967).

Meinertzhagen was a controversial character, not only a miles gloriosus, a ‘boastful soldier’, a master of espionage and an adventurer, but also an ornithologist-researcher. Such combinations are not uncommon among ornithologists and other naturalists.

At the time, 47 years ago, Meinertzhagen was considered one of Britain’s greatest ornithologists, finding many new species and subspecies on expeditions across continents, around the world.

However, he has since been exposed as a fraudster, a writer of fake diaries and reports, a forger of findings and a thief of bird skins from other people’s collections.

One by one, all his scientific discoveries were discredited. The only one that has actually been authenticated is our Afghan endemic, the snowfinch, which he named ‘Teresa’s sparrow’.

But who was Theresa? She was also a zoologist (and according to some sources, also a member of Britain’s intelligence service during the Second World War).

Theresa Rachel Clay (1911–1995) was Meinertzhagen’s cousin, thirty years his junior. She became his favourite and goddaughter at the age of fifteen, and after the mysterious death of his second wife, also his housekeeper, caretaker, associate, secretary, confidante and inseparable companion.

Meinertzhagen dedicated many of his false ornithological discoveries to his cousin Theresa, including the only one that was genuine – the species known as Afghan snowfinch.

I had the opportunity to see the endemic ‘Theresa’s sparrow’ in several places along the massif of the Hindu Kush. On 8 August 1972, I also sighted it on the Siah Koh mountain in Herat province, on a 3,000 metre-high pass between Shahrak and Jam.

This was then its most westerly-ever sighting. My happiness had no end and I boyishly believed that, with this discovery I had done a great thing for Afghanistan and ornithology. However, as will be seen below, I was mistaken. (5)

Minaret of Jam near where Voislav sighted the Afghan snowfinch in 1972, then the most westerly-ever sighting. Photo: Author

The red notebook

I recorded everything I observed about birds that summer into another notebook, my ‘red notebook’. This was my field diary. I then published my observations in French in an article for the international ornithological journal “Alauda” (Skylark).

(6) The editor-in-chief at the time was a French ornithologist Jacques Vieillard. Like some other French and Germans of the time, Vieillard himself was also interested in the birds of Afghanistan.

(7) Alas, like many ornithologists, he died of a disease while birdwatching – in his case, malaria caught in Brazil in 2010. Publishing in English scientific journals back then was not as compulsory as it is today. So, my choice to publish the article in French was not surprising at the time.

(8) However, now I see that my paper “Observations Ornithologiques en Afghanistan” (Ornithological Observations in Afghanistan) and that exciting, then most-westerly record of the Afghan snowfinch is almost forgotten, and that today’s authors almost exclusively quote English sources.

Thanks to the Afghanistan Analysts Network, many memories from that journey to Afghanistan have returned to me. I took a peek at my notebooks and diaries for the first time in many years.

I remembered the first bird that caught my eye. On my very first day in Afghanistan near the border with Iran in Herat province, I was fascinated by the common mynah (Acridotheres tristis).

This lively, curious and noisy, colourful bird of the starling family is, as its name suggests, familiar to many, but I had never seen a living specimen before.

Mynahs were originally Middle Eastern residents, but have invasively spread across the subtropical and tropical zones of the world.

I also remembered my then companion asking me what the common mynah’s Latin name, ‘Acridotheres tristis’, meant. I said it was actually a Greek-Latin name that translated as ‘Sad locust-hunter’.

“Why did it hunt grasshoppers?” she asked. “It feeds on them,” I replied. “It eats them.” Ah,” she said, “Now I see. If it has to eat grasshoppers, I understand why it’s so sad.”

During July and August of that year, I managed to travel to the most important (for me) parts of Afghanistan, observing and keeping notes on birds everywhere I went.

I also collected some specimens of reptiles and amphibians to take back to a zoologist colleague in Belgrade. I took paths that none of the earlier naturalist explorers had travelled, not even my predecessor and unofficial role model, Knud Paludan of Denmark.

(9) By all accounts, none of the ornithologists had traversed the vast Black Mountain (Siah Koh) in Herat province or visited the Hari Rud Valley, upstream of the village of Farsi, in the same province, or explored the surroundings of the minaret of Jam in neighbouring Ghor province.

By bus, truck, taxi, jeep, as well as on bicycle, horse and camel, I travelled through almost all areas of Afghanistan except the Wakhan and Nuristan, which were prohibited zones at that time.

At the Yugoslav Embassy in Kabul, I had been warned that almost all rural parts of Afghanistan were unsafe and it would be better to give up some of the remote stages of my planned itinerary. But at 27, not every warning can be taken seriously.

Some observations of daily life

While riding Afghanistan’s busy highways, but also the roads less travelled, I could not help noticing, as in neighbouring Iran, the striking presence of armed ‘askars’ (soldiers) both from army and the police.

This fitted my general impression that the crown had difficulties managing the entire country. The soldiers had interesting hats with some sort of ears or horns on the side.

Everywhere outside the cities, I saw groups of turban-wearing civilian men, not only armed but also proudly decorated with bandoliers and cartridge belts.

I liked the fact that, since the traditional costume does not have any strap over the shirt, revolvers and pistols were worn on a belt slung over the left shoulder. I was less comfortable with how they sometimes treated strangers and travellers.

Typically, instead of a ‘hello’, these men, with looks of hatred, bulging eyes and bared teeth, made two hand gestures: the first was a hand cutting the throat with the edge of the palm and the second was a sudden movement with the same hand extended upwards – meaning “There goes your head!” Later, I stopped paying attention.

In those seemingly still relatively-peaceful times in non-aligned Afghanistan, the influence of the great powers was visible to the naked eye.

In Kabul and in the north of the country, along the border with the USSR, the streets were dominated by Soviet GAZ-24 Volga cars, while in the south, especially around the US hydropower plant construction site on the Helmand River, large General Motors vehicles prevailed.

A teacher acting as a taxi driver took me in his huge 1960’s Chevrolet from Lashkar Gah to Kajaki, where the Americans were then building the famous Kajaki Dam.

The taxi driver asked me for 1,500 Afghanis (then the equivalent of 40 US dollars), a huge amount. The driver boasted that he was a serdar, meaning he was a tribal leader.

As soon as we hit the road, he stopped by his house to bring three of his relatives with him, just in case. They all sat in the front seat, next to the driver.

My companion and I were sitting in the back. Yet that trip, which started so strangely, also brought me, among other things, my first encounter with the most beautiful species of swallow – the wire-tailed swallow (Hirundo smithii) chasing insects above the waters of the Helmand River.

A straw hat for Afghanistan

Finally, I must mention my great driver-mechanic-interpreter Matin who, for three weeks drove the Toyota Land Cruiser I had rented from Hertz in Kabul. He found the things I did very strange and it was hard for him to grasp why I would expose myself to so much expense, effort and risk.

Initially, he was suspicious of me, keeping a close eye on my every move. It happened once, somewhere in the middle of a mountain desert, that I sneaked cautiously, hidden behind rocks, actually towards some very timid lizard I had never managed to catch before.

I was so focused on my potential prey that I was not even aware that the planned path of my attack was passing right next to Matin who was standing in the shade, resting against a boulder. Matin, however, followed my slow advance and wrongly concluded that I was preparing to strike him.

Of course, he had not even noticed the lizard. I later learned that he was remembering our sharp debate that morning about the direction of that day’s journey and thought I wanted to settle accounts or just get rid of him without a witness.

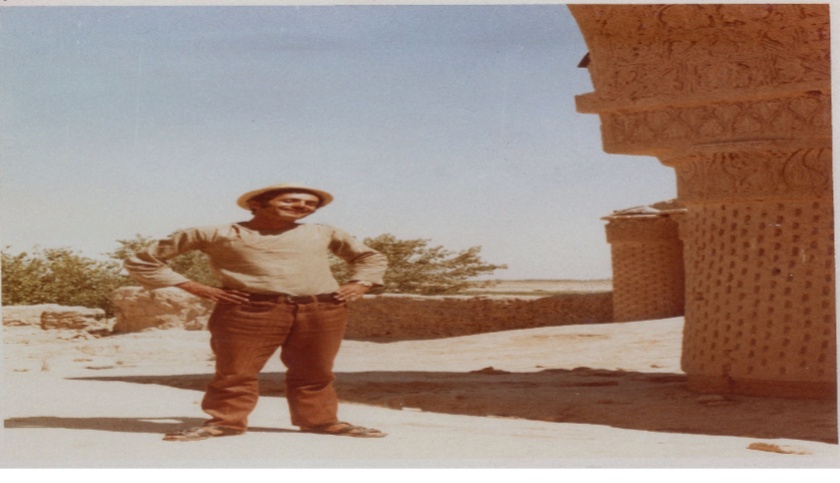

Voislav’s “great driver-mechanic-interpreter Matin.” In 1971, Matin took part in John Frankenheimer’s The Horsemen, starring Omar Sharif (photo taken at the Noh Gumbad, Afghanistan’s oldest mosque, in Balkh). Photo: Author

When I estimated that the unfortunate lizard had moved far enough from his retreat among the rocks, I rushed at it with all my might. The stones at my feet shattered, and poor Matin thought his darkest fears had come true.

Believing it was his doomsday, he screamed and started running away. I only became aware of all this when, after a goalkeeper’s dive, I found myself on the ground, covered in dust, but firmly holding the wriggling lizard in my hand.

Later, when I explained everything to the good-natured Matin, he felt bad. For a while, he was upset and refused to answer even basic questions. I then presented him with my straw hat which I knew he longed for. It was a perfect fit for him. In return, he gave me a shirt. It was too tight for me, but it had a secret pocket under a sleeve. What was it for? “For the hidden dagger (khanjar),” Matin answered.

It was unequivocally established and recorded (10) that for several years, Matin remembered the eccentric young man chasing and catching lizards, snakes, geckos and frogs, while only watching birds with binoculars. Matin, in his own words, was an actor. In 1971, he took part in John Frankenheimer’s The Horsemen, starring Omar Sharif, a movie based on the French novel, Les Cavaliers, by Joseph Kessel.

I am not sure, if, beyond one straw hat, I left any trace on Afghanistan. However, Afghanistan, for sure, left a very deep impression on me.

Edited by Jelena Bjelica and Kate Clark