Australia’s special forces problem : Why the SAS is facing a crisis?

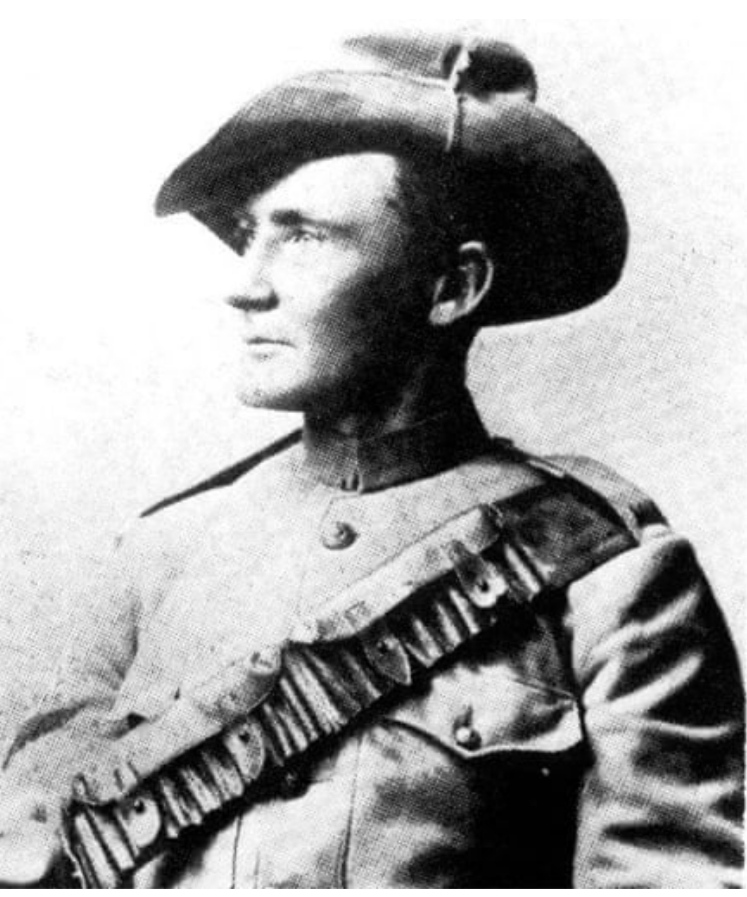

The Australian special forces are as steeped in mythology as Australia’s early troops, the Colonial Bushmen, who fought in various British units in the Boer war, and eventually evolved into the Light Horse regiments of world war one.

The SAS and the commandos, meanwhile, have their Australian genesis in the independent companies that fought behind Japanese lines in the Pacific during world war two.

All were mired in controversy that shocked the Australian polity and public, starting with the conviction and execution of the Australian lieutenants Harry “Breaker” Morant and Peter Handcock for murdering Boer civilians and prisoners of war. In 1918 Australian light horsemen took part in the massacre of dozens of Arab men and boys in the Palestinian village of Surafend and at a nearby Bedouin camp.

There have been persistent suggestions that after the Japanese surrender 75 years ago this month Australian soldiers, some belonging to the independent companies, summarily executed and otherwise mistreated prisoners in Borneo and New Guinea.

Such truths clash with Australia’s nurtured Anzac myths encompassing loss, sacrifice, mateship, endurance and egalitarianism. Australia has never liked to scrutinise the human impact of the wars it fights, and the capacity for combat to impel soldiers – otherwise good men – to commit immoral, inhumane acts.

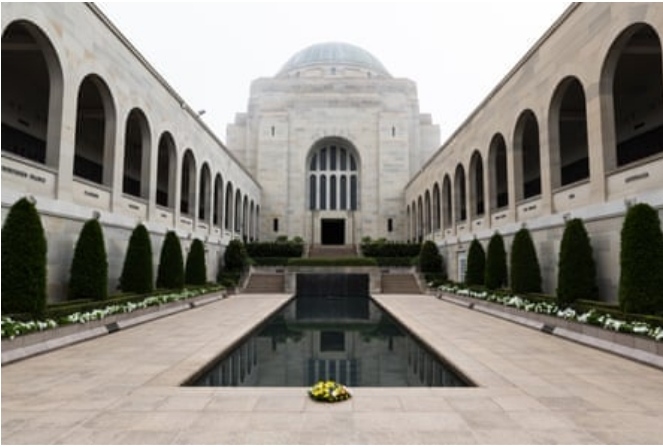

There is little in the war memorial, over which the presence of Ben Roberts-Smith VC looms so large, that details such stories.

Why? Because the simple trope of Anzac mythology is heroism, whereas the brutal reality of war fighting is complex and ugly.

An inquiry into allegations of war crimes committed by a small number of elite troops in Afghanistan is expected to report imminently. Can the regiments survive the fallout?

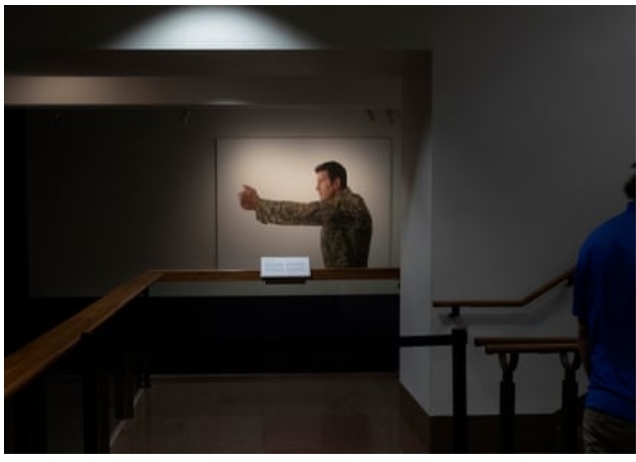

In the heart of the Australian War Memorial hang twin portraits of Ben Roberts-Smith, the most decorated soldier of his time and now its most controversial former special forces warrior.

The first of Michael Zavros’s paintings is modestly sized, dignified in composition. Roberts-Smith, 41, stands in full military uniform, gazing intently, tunic breast filled with medals including his Victoria Cross, Australia’s highest honour.

It pales beside the other painting, Pistol grip, a monumental 1.6 by 2.2-metre portrait presenting the imposing fighter in special forces fatigues, arms extended in combat pose, hands gripping an invisible handgun, finger on the trigger.

Zavros recalled on the AWM website that upon asking Roberts-Smith to adopt a fighting stance, “He went to this whole other mode. He was suddenly this other creature and I immediately saw all these other things. It showed me what he is capable of … it was just there in this flash.”

Just as this larger-than-life image of Roberts-Smith looms over the war memorial, the nation’s secular shrine to Anzac, so, too, do investigations into him and other exceptional soldiers cast ominous shadows over Australia’s special forces, including the Special Air Service, the regiment the VC winner served in until 2013 including during six tours of Afghanistan in as many years.

Since 2016 Paul Brereton, the Australian defence force inspector general, has been conducting an inquiry into allegations of war crimes by a small number of special forces troops in Afghanistan. Brereton – who is reported to have interviewed some 250 former and serving special forces soldiers – is due to imminently report to the federal government.

The government is managing expectations ahead of the release of the Brereton report, warning that it will make for “uncomfortable reading” and could lead to significant structural reform of the special forces.

The defence minister, Linda Reynolds, said the regiments had undertaken “a significant amount of self-reflection on how some of these reported circumstances could have happened, and what needs to happen structurally and culturally to make sure that these events do not happen again”.

A first step towards an expected major restructure has already been taken with the appointment of former commando Paul Kenny as the new special operations commander – a role usually filled by an ex-SAS officer.

Roberts-Smith, now employed as a manager in Queensland for Kerry Stokes’s Seven Network, features in the inspector general’s investigations.

It has been reported Roberts-Smith is being investigated by Australian Federal Police in relation to alleged war crimes in Afghanistan.

Roberts-Smith has vehemently denied the allegations, reportedly claiming his anonymous accusers were motivated by professional jealousy and personal vendettas.

He is also suing former Fairfax newspapers over a series of 2018 articles that he claims defamed him because they portrayed him as someone who “broke the moral and legal rules of military engagement”.

He has previously rejected the allegations of misconduct as malicious and deeply troubling.

Roberts-Smith’s defamation lawyer, Mark O’Brien, told the Guardian: “My client’s position has not changed. Nothing more to add.”

While Roberts-Smith is the highest profile member of Australian special forces in question, allegations of unnecessarily brutal behaviour by other serving and former SAS and commando soldiers in Afghanistan are also being investigated – including for summarily executing, and otherwise abusing, unarmed suspected militants and civilians.

The SAS cap badge

The alleged misconduct – which includes SAS members flying the US Confederate flag (with its racist/white supremacist connotations) while on operation – has been exposed in a series of reports over several years by ABC and Nine newspapers journalists.

The government may be inclined to keep the inquiry’s findings secret. But it will face immense pressure to release the Brereton report which, by its very necessity, implies the need for dramatic reform of the special forces, which include the SAS and two commando regiments.

It is, in the words of one source close to the SAS, “potentially existential” for the regiment based on the British Special Air Service, with which it shares the motto “Who Dares Wins” and the winged dagger emblem.

Indeed, some former and serving members of the SAS believe the Brereton inquiry and the police investigations could inspire a special forces restructure, with a focus on the SAS.

Sources insist it could even result in the SAS headquarters being moved to the east coast from Swanbourne outside Perth, where it has been since the 1957 establishment of its first company – far from the gaze of Special Operations Command at Bungendore, a continent’s width away just outside Canberra. Some say it might even result in an even more radical restructure – even a renaming – of the regiment.

The politicians will decide. And Anzac (central to which is the unqualified political support of its temple, the war memorial) has always had a way of engendering unmatched bipartisan consensus.

While individual soldiers are likely to face military and/or civilian charges, both the Brereton inquiry and the police investigations are set to expose serious systemic deficiencies in special forces – especially SAS – chains of command and structure. Questions are already being raised about the unnecessarily high number of rotations some soldiers and officers have undertaken and continue to undertake, and the willingness of successive governments to deploy large numbers of SAS and commando troops to remote US-led wars where regular infantry troops would have sufficed.

So, how did the Australian special forces – and especially the revered SAS – end up in this potentially existential crisis?

‘Heat of combat under the fog of war’

The unpalatable reality of how Australia’s most skilled soldiers have sometimes conducted themselves, from the Boer war to contemporary operations in Afghanistan, has always contradicted the well-cultivated myth of the white-hatted Aussie-Anzac “digger”.

Australian War Memorial : the remarkable rise and rise of the nation’s secular shrine

No element of our military has been more mythologised, praised or mystified than the SAS. This helps explain why, as investigations into alleged special forces war crimes in Afghanistan culminate, the guardians of Anzac myth have criticised so rancorously those exposing such purported grave misconduct.

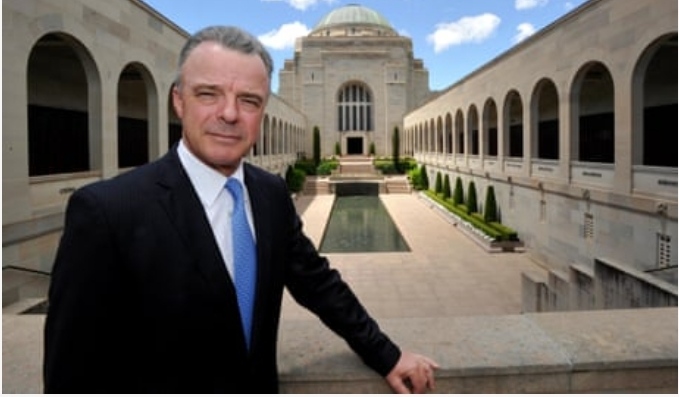

The former war memorial director and defence minister Brendan Nelson, the one-time prime minister Tony Abbott and Stokes – Roberts-Smith’s employer, chair of the memorial’s council and a generous bankroller of AWM exhibitions, who has purchased and donated numerous Victoria Cross medals to the institution – have all supported with deeds and words Roberts-Smith and the SAS in these times of controversy.

Abbott told the Australian newspaper people should be cautious to “judge soldiers operating in the heat of combat under the fog of war by the same standards that we would judge civilians”.

The Anzac skull that tells a shocking and tragic story of battlefield violence

Nelson strongly backed Roberts-Smith, insisting some allegations by journalists about him were an attempt to “tear down our heroes”.

“I am very concerned that if the media pursuit of Ben Roberts-Smith and others continues … we run the risk of becoming a people unworthy of such sacrifice,” he said.

He insisted he didn’t “doubt that what you and I might think, in the cold, hard light of day, that bad things have happened. War is a messy business.

“But as far as I am concerned, unless there have been the most egregious breaches of laws of armed conflict, we should leave it all alone.”

Stokes has supported Roberts-Smith’s long, costly defamation action against Nine newspapers, which has included the engagement of a public relations firm whose own award-winning investigative journalist has dissected the journalistic methodology behind the allegations against the VC winner.

The SAS is revered. But despite the views of some prominent boosters who seem to suggest its alleged misdeeds would best remain shrouded in the fog of war, it is not sacrosanct or beyond reproach.

Exemplifying what can happen when elements of an elite unit go bad is the 1993 “Somalia affair” during which rogue members of Canada’s Airborne Regiment unlawfully killed people while deployed in Somalia. The regiment was abolished.

The adjectives “secretive” and “elite” have always preceded most mentions of the SAS, revered globally as “the best of the best” since its first deployment to Borneo during the “confrontasi” with Indonesia in 1965.

Based on the British SAS and with its genesis in the combat experiences of Australia’s world war two M and Z special units, the independent commando companies and the Coastwatchers, the Australian SAS was designed to carry out long-range covert intelligence, reconnaissance and strike operations in small teams, often behind enemy lines. It also has a major domestic counter-terrorism function.

The SAS has enjoyed a standout reputation for ingenuity, ruthless efficiency, bravery and discipline for its operations in Borneo, Vietnam, Somalia, Timor-Leste, Iraq and Afghanistan – and on numerous peacekeeping deployments.

Reflecting its international reputation, the then commander of the US Marine Corp, Jim Mattis, who fought alongside the SAS in Afghanistan from 2001, wrote to the regimental commander, Gus Gilmore, “We Marines would happily storm hell itself with your troops on our right flank.”

‘Sickened, disgusted and really very angry’

Serving and former special forces soldiers are part of an exclusive brethren. Present and past soldiers don’t much talk about what they’ve done – except to each other. Many remain in close contact and continue to have insight into current operations and command efficacy.

One former senior SAS member said he had first heard allegations about serious misconduct in 2009 or 2010.

“Unfortunately, it has been known for a very long time that these allegations were around,” he said. “Everyone with any association with the regiment has heard about them and questions were being raised long before any of this made the media.

“So, with BRS you have to remember that Betty Windsor has pinned it on this guy’s chest [the Queen’s representative, then governor general Quentin Bryce, presented the Victoria Cross to Roberts-Smith in 2011].

If it’s got to be un-pinned the shame to the regiment will be significant … many are mindful of what happened to the [Canadian] Airborne. It’s possible that the regiment could be restructured or more as a consequence of all of this.”

Governor general Quentin Bryce congratulates Corporal Benjamin Roberts-Smith after awarding him the Victoria Cross at an investiture ceremony in Swanbourne, outside Perth, in January 2011.

Jim Truscott is a former special forces officer who served in the SAS and commando regiments. He says regimental alumnae are “sickened, disgusted and really very angry that this very long delay in the release of the report has been allowed to happen”.

“What would appear to have happened is a breakdown in the chain of command,” says Truscott, 64. “And while on the surface it might seem like an individual or individuals have done something wrong, or potentially done something wrong, the system should have known about it.

“And the system should have known about it very quickly and something should have been done about it, right there and then. And the fact that this has taken … many years to bubble up is an anathema to me.”

Truscott questions if the traditional routine procedure of the “hot debrief” was carried out after all SAS patrols and combat operations in Afghanistan in the relevant period – the decade from about 2005.

“That was so important because what that would immediately do is identify deficiencies. It wasn’t just to glean intelligence … it was to expose if you stuffed up. How are you going to stop the stuff-up from happening again, you know?”

Truscott agrees one possibility is that alleged bad behaviour was known about at senior levels – and perhaps even in government – but nothing was done about it.

“And if that’s the case how far up the chair of command was it hidden? Was it an act of commission or omission? We don’t know. All I’m saying is that the debriefing procedure almost certainly has broken down because this thing should’ve been fixed right at the start.

“The fact no one has done anything about it is a travesty. Perhaps the fault lies in the chain of command, not with individuals. If indeed something wrong has happened.”

In 2001 the SAS was deployed in a highly politicised military operation – the seizing of the MV Tampa, a Norwegian freighter.

The ship carrying hundreds of asylum seekers, rescued from a stranded fishing boat in the Indian Ocean, was attempting to bring them to Australia. The SAS, on the order of the then prime minister, John Howard, seized the vessel – an illustration, on the eve of a federal election, that his government was serious about border control.

The scandal now engulfing Australia’s special forces has an equally, though perhaps less obvious, political genesis.

Since the first gulf war in 1990 through to this century’s repeated operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, Australian special forces have been the answer when the US has called for Australian boots on the ground.

The SAS is in a constant high state of readiness (one of the commando regiments, in contrast, comprises, in part, reservists) and its personnel are Australia’s most highly trained soldiers, their efficiency and lethality unparalleled.

Australian prime ministers from both major parties have operated on a premise they would experience greater electoral pain associated with high battlefield fatalities if they deployed regular infantry instead of special forces, especially SAS. The special forces are not easily killed.

But a combination of high rotation (some SAS members and commandos deployed up to eight times over periods of several years), leadership shortcomings at regimental headquarters and the over-deployment of senior commanders who ought to have remained on base is alleged by some to have led to the erosion of the SAS’s disciplinary culture.

The SAS ethos is founded on independent thinking, rigorous self-discipline and post enemy-contact debriefing where, rank regardless, men would openly discuss – and criticise without repercussion – suboptimal operational aspects.

There is little adherence to the strictures of formal military custom; first names are used without deference to rank, the rules on hair (including facial hair), uniform and kit are relaxed.

An Australian infantry soldier on exercise in July 2019.

It is possible, sources say, regimental recruits have mistaken a laissez-faire approach to military protocol as licence for individual ill-discipline that is antithetical to traditional regimental self-regulation.

Sources say SAS command has been “diluted” by the promotion of too many officers to other roles outside the regiment.

Too many warrant officers, meanwhile, have been promoted to officers from within the ranks, resulting in a diminution of the non-commissioned officers corps and potential misunderstanding among newer personnel of traditional unit culture.

In a high-rotation environment in Afghanistan, the SAS and commando regiments also sometimes found themselves effectively “competing for work”.

“I’ve served in both [SAS and commando] units and it’s a travesty that such tribalism has arisen,” Truscott says. “It’s just possible … that the tribalism was so great that it was like ultra-competition in sport, you know? When elite sports people get to that level, competition is so fierce to stay in front that bad things happen.

“You have an alpha-type personality prevailing through that regiment. It needs to be very carefully controlled. What we are seeing and hearing right now possibly points to a dramatic failure of individual self-discipline and command.”

A former SAS officer says, “Blame is easy to attribute to tactical elements involved in the most complex combat environment [in Afghanistan] that Australians have faced in decades. Nonetheless, the regiment has much to answer for– a lack of leadership, foresight, immaturity and just plain common sense has led to this deplorable state of events.

All that at a local level – but exacerbated by more serious problems at senior levels inclusive of successive governments of both persuasions that have cheerfully prostituted our country to the requests of the US and to a lesser degree a motley collection of allies referred to as ‘the coalition of the willing’ – all that at the self-import of playing on the international stage.”

John Blaxland, professor of international security and intelligence studies at Australian National University and a former army intelligence officer, says it is “imperative we get to the truth about what happened”.

“Australians have been justifiably proud of their defence force exactly because they set and maintain exemplary standards,” Blaxland says. “For the part of society tasked and mandated to conduct lethal acts, the absolute highest standards have to be set, maintained and seen to be maintained. The moral authority of the ADF is on the line.

“Beyond this, the worst aspects need to be seen in the context of a long war, with insufficiently defined objectives, where we, as a nation, demanded too much of too few – notably our special forces. We over-relied on them, sending them time and time again.

Is it any wonder that, with unclear strategic objectives set for Australia’s Afghanistan mission and shifting operational plans, year in and year out in the same bloody province, that somehow some of the special forces lost the bearings on their moral compass? We as a society need to be held to account for this and not just the special forces members involved. We allowed this to happen.”

Blaxland identifies an “understandable emotional pull” for public figures invested in supporting the Australian military, in particular the special forces, but says “now is not the time to unquestioningly defend any and all their actions”.

“Extreme human behaviour, involving the killing of unarmed and detained individuals, flies in the face of the ethics and values instilled in our society and upheld, with few exceptions, by the ADF. To be sure, our adversary did such things and much worse.

They set a very low bar. But we expect our soldiers to act differently, as ambassadors for a liberal open democratic society, prepared to use lethal force, but only when necessary, when authorised and in a manner proportional to the circumstances, without overkill.”

Much of the cultural and political backlash to Nine’s and the ABC’s investigatons into the special forces are freighted with implied suggestions that elite soldiers are somehow above the law and that transgressions ought to be overlooked.

In his 2005 book, The Amazing SAS, the bestselling author and former News Corp defence correspondent Ian McPhedran warned of the risks of over-deploying the regiment.

The challenge of ensuring justice where national heroes are involved, he says, “rests with the politicians who send them to war and the generals who are ultimately responsible for their behaviour”.

Chief of the Australian defence force General Angus Campbell in January 2020.

“Too often with our defence force we have seen mid-ranking officers or diggers take the fall for the systemic failures of those at the top. This is a key factor in the current situation,” McPhedran says.

“It is these same politicians and generals who will decide what the public will be allowed to know [about the Brereton report].

“I would caution those blindly defending the special forces and their high-profile heroes to tread warily given the video evidence of egregious war crimes that has come to light. It has nothing to do with tearing down heroes as there is simply no excuse for cold-blooded murder under any circumstances. It is now clear that such crimes were committed by Australian soldiers more than once in Afghanistan.”

Defence did not specifically address a series of Guardian Australia questions relating to the conduct, chain-of-command issues and potential restructure of Australian special forces raised in this article.

“The Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force (IGADF) is conducting an Inquiry into rumours and allegations relating to the conduct of Australia’s Special Operations Task Group in Afghanistan over the period 2005 to 2016,” a defence spokesperson said.

“On completion, the IGADF [inspector general] will release the Inquiry report to the Chief of the Defence Force, who will consider its findings and determine appropriate actions.

“Until this time and in order to protect the integrity and independence of the Inquiry, and the reputation of individuals involved, it is not appropriate for Defence to comment further.”

Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, circa 1900