Belt and Road Initiative – Strategic Goals – Now A Debt Trap – Security Implications India

Belt and Road Initiative – Strategic Goals – Now A Debt Trap – Security Implications India.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an ambitious program to connect China with Asia, Africa and Europe via land and maritime networks along six corridors with the aim of improving regional integration, increasing trade and stimulating economic growth. The name was coined in 2013 by China’s President Xi Jinping, who drew inspiration from the concept of the Silk Road established during the Han Dynasty 2,000 years ago – an ancient network of trade routes that connected China to the Mediterranean via Eurasia for centuries. The BRI has also been referred to in the past as ‘One Belt One Road’.

Ancient Silk Route

The BRI comprises a Silk Road Economic Belt – a trans-continental passage that links China with south east Asia, south Asia, Central Asia, Russia and Europe by land – and a 21st century Maritime Silk Road, a sea route connecting China’s coastal regions with south east and south Asia, the South Pacific, the Middle East and Eastern Africa, all the way to Europe.

Maritime Silk Road.

The initiative apparently sees five major priorities, policy coordination; infrastructure connectivity; unimpeded trade; financial integration; and connecting people. The entire program is expected to involve over US$1 trillion in investments, largely in infrastructure development for ports, roads, railways and airports, as well as power plants and telecommunications networks. The geographical scope is constantly expanding. So far it covers over 70 countries, accounting for about 65 per cent of the world’s population and around one-third of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The real goal for Beijing is to promote regional connections and economic integration, thereby expanding China’s economic and political influence.

Countries which signed cooperation documents related to the Belt and Road Initiative. China’s Economic and Strategic Model

China’s economic growth has begun to slow. Their entire Chinese economic model has been based on mass producing cheap imitations of western products and flooding the foreign markets. Often the quality and reliability was an issue. Lowly paid Chinese labour was pulled out of villages, trained to manufacture on low technology products, then packed like sardines into over-crowded factories in shanty towns. such cheap products were then exported across the world. Their target was mostly the lower middle class and the poor who wanted products that looked like the ones used by rich, and thus gave them social status. Soon the world started realising that many products were sub-standard and had issues related to reliability and personal health safety. In due course, cash rich China started doing research and making better quality products. Finding export markets for its produce is the most critical economic requirement. So emerged the idea of BRI which was less to support a poor country to develop its infrastructure, but more a model to create connectivity to perspective markets. Cash rich Chinese government banks were asked to give relatively cheap loans to these countries. In most cases the countries will not be able to pay debt and would indirectly become indebted to China. In many cases they would give important strategic assets such as ports to China on long lease. China would also get a foot hold in the countries they invest in, something akin to what East India Companydid when they firsts set foot in India in 1600s. Other than the normal marketing of Chinese produce, China found it convenient to use surplus Chinese steel and cement production. Also Chinese have positioned large number of armed police personnel in these countries in the garb of securing their assets.

Chinese Centrally Coordinated Mass production.The Geographical Pivot of History – Sir Halford John Mackinder Theory

According to Mackinder, theory published in 1904, the Earth’s land surface was divisible into three zones. The World-Island, comprising the interlinked continents of Europe, Asia and Africa. This was the largest, most populous, and richest of all possible land combinations. The second was the offshore islands, including the British Isles and the islands of Japan. And the third, the outlying islands, including the continents of North and South America, and Oceania. The Heartland lay at the centre of the world island, stretching from the Volga to the Yangtze and from the Himalayas to the Arctic. Mackinder’s Heartland was the area then ruled by the Soviet/Russian Empire. Any power which controlled the World-Island would control well over 50% of the world’s resources. The West European powers had therefore combined, to prevent Russian expansion. The Russian Empire remained huge but socially, politically and technologically backward. One of BRI’s implicit targets is to get access and try control the “World Island”.

Integrating Western China

BRI’s goals include internal state-building and stabilisation of ethnic unrest for its vast inland western regions such as Xinjiang and Yunnan, linking these less developed regions, with increased flows of international trade facilitating closer economic integration with China’s inland core. China sees the countries around its west weakened after the Soviet dissolution. China thinks it is right time to increase influence. As USA pulls out of Afghanistan, and is muscle flexing with Iran, China would like to move in closer with them using BRI projects as bait.

Western China and Neighbourhood. BRI Land Corridors

The New Eurasian Land Bridge, runs from Western China to Western Russia through Kazakhstan, and includes the Silk Road Railway through China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany. The China-Mongolia-Russia Corridor will run from Northern China to the Russian Far East. The China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor will run from Western China to Turkey. The China–Indochina Peninsula Corridor, will run from Southern China to Singapore. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) aims to rapidly modernize Pakistan’s transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and economy. On 13 November 2016, CPEC became partly operational when Chinese cargo was transported overland to Gwadar Port for onward maritime shipment to Africa and West Asia.

BRI Land Corridors21st Century Maritime Silk Road

The “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” is the sea route ‘corridor.’ It is an initiative aimed at investing and fostering collaboration in Southeast Asia, Oceania and Africa through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area.

Among the G7 industrial country Italy has been a partner in the development of the project since March 2019. Trade along the Silk Road could soon account for almost 40% of total world trade, with a large part being by sea. The land route of the Silk Road also appears to remain a niche project in terms of transport volume in the future. In the maritime silk road, which is already the route for more than half of all containers in the world, deepwater ports are being expanded, logistical hubs are being built and new traffic routes are being created in the hinterland. The maritime silk road runs with its connections from the Chinese coast to the south via Hanoi to Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpurthrough the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo towards the southern tip of India via Male, the capital of the Maldives, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then through the Red Sea via the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central Europe and the North Sea.

As a result, Poland, the Baltic States, Northern Europe and Central Europe are also connected to the maritime silk road and logistically linked to East Africa, India and China via the Adriatic ports and Piraeus. All in all, the ship connections for container transports between Asia and Europe will be reorganized. In contrast to the longer East Asian traffic via north-west Europe, the southern sea route through the Suez Canal towards the junction Trieste shortens the goods transport by at least four days. In connection with the Silk Road project, China is also trying to network worldwide research activities, for its own benefit.

The Arctic or Ice Silk Road

In addition to the Maritime Silk Road, Russia and China are reported to have agreed jointly to build an ‘Ice Silk Road’ along the Northern Sea Route in the Arctic, along a maritime route which Russia considers to be part of its internal waters. Chinese and Russian companies are seeking cooperation on oil and gas exploration in the area.

Super Electric Power Grid

The super grid project aims to develop six ultra high voltage electricity grids across China, north-east Asia, Southeast Asia, south Asia, central Asia and west Asia. The wind power resources of central Asia would form one component of this grid.

Types of BRI Participants and Motivation

Some of the major participants are the relatively poor developing nations who thing that the BRI initiative will help them build good quality infrastructure and improve the living conditions of their people and give a fillip to their economy. the second group of participants are those who think that this infrastructure would get them market access to China and other countries. However one of the world’s largest future market like India has not chosen to participate.

China’s Political Stakes – Quantum of Debt

President Xi Jinping considers BRI his personal baby and invested his entire political standing on its success. The scale and magnitude of the BRI project requires it to be controlled at the highest level in the government, and a special committee has been formed to oversee it. Will the huge debt be the reason of its ultimate demise is what many are questioning. Amanda Lee writes in South China Morning Post, that according to an estimate by the Institute of International Finance (IIF), since 2013, China has agreed to US$690 billion in overseas investments and construction contracts in more than 105 countries. And by narrowing that focus down to 72 countries involved in BRI projects, the IIF also estimated that China has funneled a total of US$280 billion into 44 countries that are either not rated or do not have an investment-grade rating assigned by Fitch Ratings, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s. In the first quarter of 2020, the value of belt and road projects, including projects with Chinese involvement, exceeded US$4 trillion for the first time. Among these, 1,590 projects – valued at US$1.9 trillion – were BRI projects, while 1,574 other projects with a combined value of US$2.1 trillion were classified as projects with Chinese involvement. In addition there are many projects with Chinese involvement but not officially included in the category BRI, though they serve the same purpose.

BRI Risk Assessment.

The World Bank estimated last year that around US$500 billion was invested in belt and road projects in 50 developing countries between 2013 and 2018. Of that amount, about US$300 billion was estimated to have been financed via public and publicly guaranteed debt. BRI accounted for very significant 13.5 per cent of China’s overall foreign investment in 2019, according to the IIF. China is now the world’s largest creditor to developing countries, with a significant portion for BRI. Washington has called China’s belt and road lending a “debt trap”, saddling countries with debt that they will not be able to repay. China accounts for more than 25 per cent of the total external debt of countries eligible for the G20’s debt-suspension scheme, making China the single-largest bilateral creditor. In this group, Chinese loans to Djibouti, Ethiopia, Laos, the Maldives and Tajikistan are rated as having a “high” risk of debt distress, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Quantum of Investment.Extending International Influence

The BRI is a way to extend Chinese influence. While China attempts to mask any strategic dimensions of the BRI, China has already invested billions of dollars in several South Asian countries like Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan to improve their basic infrastructure, with implications for China’s trade regime as well as its military influence. China has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sources of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into India – it was the 17th largest in 2016, up from the 28th rank in 2014 and 35th in 2011, according to India’s official ranking of FDI inflows.

Leading to China as Super Power 2049

The stated objectives are “to construct aunified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, ending up in an innovative pattern with capital inflows, talent pool, and technology database.” The Chinese government calls the initiative “a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future“. Some observers see it as a plan for Chinese world domination for a China-centered global trading network. The project has a targeted completion date of 2049, which coincides with the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. The initial focus has been infrastructure investment, education, construction materials, railway and highway, automobile, real estate, power grid, and iron and steel.

The project builds on the old trade routes that once connected China to the west, Marco Polo’s and Ibn Battuta’s Silk Road in the north and the maritime expedition routes of Admiral Zheng He in the south. Development of the Renminbi as a currency of international transactions, development of the infrastructures of Asian countries, strengthening diplomatic relations whilst reducing dependency on the US and creating new markets for Chinese products, exporting surplus industrial capacity, and integrating commodities-rich countries more closely into the Chinese economy are all objectives of the BRI. Clearly implicit in it is a desire to replace USA as the future super power. The project aims to push Chinese influence. It is “The Hundred Year Marathon” as the famous book by Michael Pillsbury says.

Bulk of the debt is coming from China’s three largest state-owned banks.China has also created sovereign wealth funds such as the Silk Road Fund. International financial institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank are also being coaxed by China to dish out loans to many BRI participating countries. Chinese investments in developing countries have raised questions about whether such projects can ever generate enough money to pay off the debt. The writing is on the wall. Beijing is thus looking at the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative, which offers relief for 77 developing nations’ debt repayments this year – on a case-by-case basis. China is also ensuring that these loans are offered with no specific mention of “belt and road”, so as to remain clean in case of defaults. According to open source data, over 50 per cent of the projects are owned by government agencies in recipient countries, 30 per cent by private sector, and 20 per cent are public-private ventures.

The Health Silk RoadCoronavirus Impact on BRI

Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, China’s Communist Party (CCP) has quickly tried to turn this crisis into a geo-economic opportunity, swiftly moving the attention from being the source of the virus to the one offering solutions. In the process, Beijing has been employing soft power tools such as mask diplomacy. Seizing the initiative in a leaderless Covid-19 world. The economic impact of Coronavirus has resulted in Chinese lenders wanting to reassess the lending and Beijing’s initiative to reduce the high national debt load and risky lending, has caused serious difficulties to recipient nations. Also Coronavirus has hit BRI due delays in supplies of materials and availability of workers. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that about 20 per cent of BRI projects had been “seriously affected”. Some analysts have said that the pandemic, coupled with slow domestic growth, may force China to scale back some of its belt and road projects.

Debt Game Plan and Sustainability

According to Carmen Reinhart, the World Bank’s chief economist, 60% of the lending from Chinese banks are to developing countries where sovereign loans are negotiated bilaterally, and in secret. Loans are backed by collateral such as rights to a mine, a port or money. Critics use the term debt trap diplomacy to claim China intentionally extends excessive credit to another debtor country with the alleged intention of extracting economic or political concessions from the debtor country when it becomes unable to honor its debt obligations (often asset-based lending, with assets including infrastructure). The conditions of the loans are often not made public and the loaned money is typically used to pay contractors from the creditor country. For China itself, a report from Fitch Ratings doubts Chinese banks’ ability to control risks, as they do not have a good record of allocating resources efficiently at home, which may lead to new asset-quality problems for Chinese banks that most funding is likely to originate from. It has been suggested by some scholars that an evolving BRI and its financing needs to transcend the “debt-trap”. This concerns the networked nature of financial centers and the vital role of advanced business services (e.g. law and accounting) that bring agents and sites into view (such as law firms, financial regulators, and offshore centers) that are generally less visible in geopolitical analysis, but vital in the financing of BRI.

The COVID-19 pandemic has stopped work on some projects, while some have been scrapped; focus has been brought on projects that were already of questionable economic viability before the pandemic. Many of the loans agreed upon are in or nearing technical default, as many debtor countries reliant on exporting commodities have seen a slump in demand for them. Some debtor countries have started to negotiate to defer payments falling due. In particular, the African continent that has been targeted by China owes an estimated $145 billion, much of which involves BRI projects, with $8bn falling due in 2020. Many leaders on the continent are demanding debt forgiveness, and The Economist forecasts a wave of defaults on these loans.

BRI – Corruption and Other Issues

BRI has also attracted criticism for perceived a lack of transparency, corruption, environmental impact, legal issues and labour problems. The East Coast Rail Link, an infrastructure project to connect the South China Sea at the Thai border in the east with the strategic shipping routes of the Strait of Malacca in the west, was suspended in 2018by the then newly elected Malaysian prime minister, Mahathir Mohammad, following his pledge to cut national debt and to renegotiate or cancel what he called “unfair” Chinese mega-projects approved by his predecessor, Najib Razak. After several round of talks, China and Malaysia agreed in April 2019 to proceed with the infrastructure project at a lower cost of 44 billion ringgit (US$10.3 billion) – about a third less than the initial price tag of 65.5 billion ringgit. London-based research firm Chatham House said in a March report, examining Chinese investments and the Belt and Road Initiative in Sri Lanka, that there was a need for both countries to consider the financial feasibility, security and disclosure in such projects to promote public trust.

Below the Belt and Road Corruption and Illicit Dealings in China’s Global InfrastructureSeeking Collaborative Support

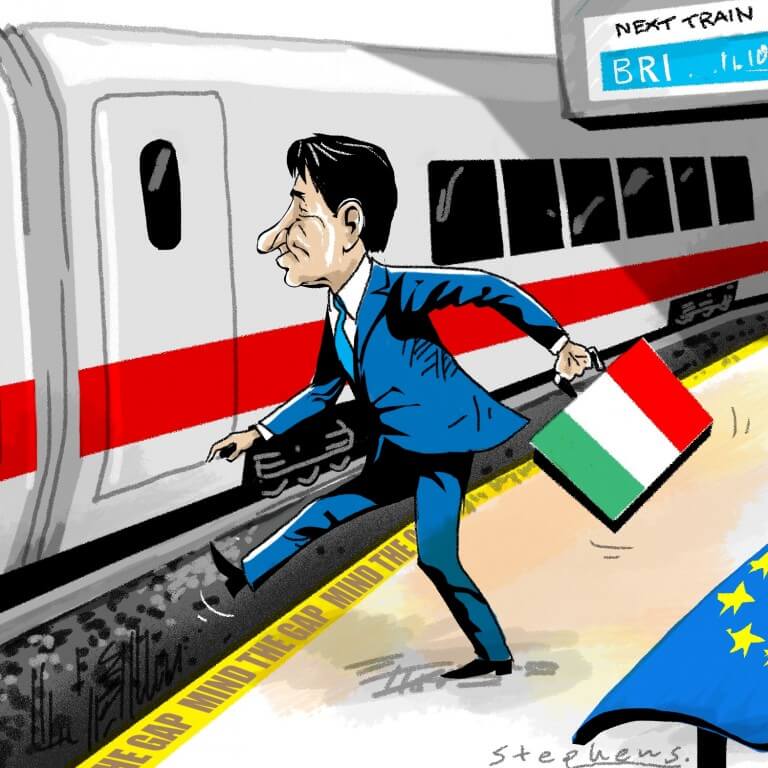

China has tried to get many countries on board to make the project look all inclusive. Singapore does not need massive external financing or technical assistance for domestic infrastructure building but repeatedly endorsed the BRI and cooperated in related projects in a quest for global relevance and to strengthen economic ties with BRI recipients. The Philippines historically has been closely tied to the United States, China has sought its support for the BRI in terms of the quest for dominance in the South China Sea. In April 2019 and during the second Arab Forum on Reform and Development, China engaged in an array of partnerships called “Build the Belt and Road, Share Development and Prosperity” with 18 Arab countries. The general stand of African countries sees BRI as a tremendous opportunity for independence from the foreign aid and influence. Greece, Croatia and 14 other eastern Europe countries are already dealing with China within the framework of the BRI. In March 2019, Italy was the first member of the G7 nations to join the Chinese Initiative.

Debt-laden Italy joins China’s BRI.Serious Opposition to BRI

The United States proposes an initiative called the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy” (FOIP). US officials have articulated the strategy as having three pillars – security, economics, and governance. At the beginning of June 2019, there has been a redefinition of the general definitions of “free” and “open” into four stated principles – respect for sovereignty and independence; peaceful resolution of disputes; free, fair, and reciprocal trade; and adherence to international rules and norms. India have repeatedly objected to the BRI, specifically because they believe the CPEC project ignores New Delhi’s essential concerns on sovereignty and territorial integrity. Vietnam historically has been at odds with China. Vietnam has been indecisiveabout support or opposition to BRI. South Korea has tried to develop the “Eurasia Initiative” (EAI) as its own vision for an east–west connection. While Italy and Greece have joined the Belt and Road Initiative, European leaders have voiced ambivalent opinions. Angela Merkel declared that the BRI “must lead to a certain reciprocity, and we are still wrangling over that bit.” In January 2019 Macron said: “the ancient Silk Roads were never just Chinese … New roads cannot go just one way.” European Commission Chief Jean-Claude Juncker and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe signed an infrastructure agreement in Brussels in September 2019 to counter China’s BRI and link Europe and Asia to coordinate infrastructure, transport and digital projects. The Australian home affairs minister, described BRI as “a propaganda initiative from China” that brings an “enormous amount of foreign interference.”

BCIM. Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor

BCIM which runs from southern China to Myanmar and was initially officially classified as “closely related to the BRI “. Since 2019, BCIM has been dropped from the list of covered projects due to India’s refusal to participate in the BRI.

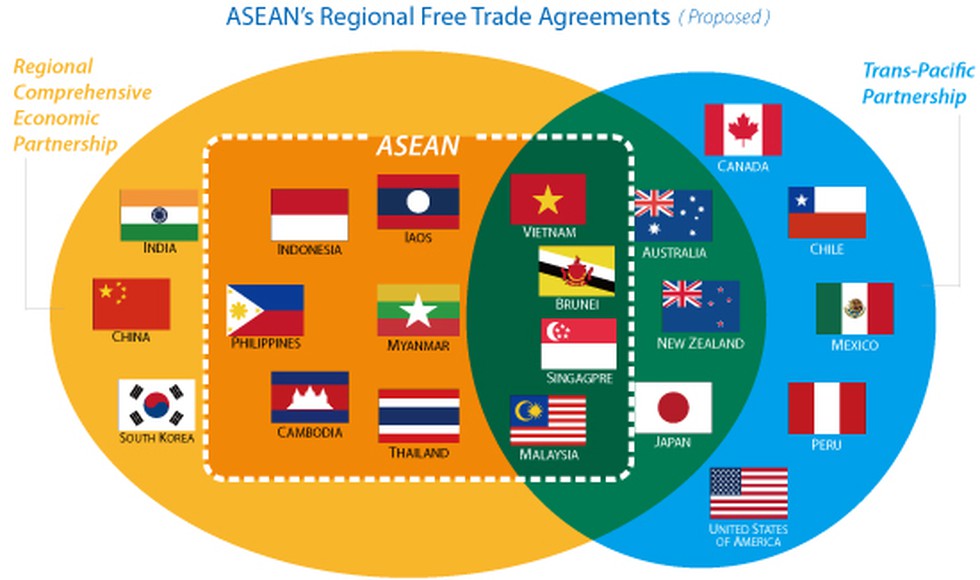

India and RCEP

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a proposed free trade agreement in the Indo-Pacific region between the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), namely Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, and five of ASEAN’s FTA partners—Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea. India, which is also ASEAN’s FTA partner, opted out of RCEP in November 2019. Without India, the 15 negotiating parties account for 30% of the world’s population and just under 30% of the world’s GDP. India runs a large trade deficit with RCEP countries and was looking for specific protection for its industry and farmers from a surge in imports, especially from China. India has trade deficits with 11 of the 15 other RCEP members, many of them sizable. Taking that into account, at the start of negotiations, India had demanded a three-tiered structure for phasing out its tariffs for different groups of countries. For example, India would have provided an initial tariff reduction on 65 percent of goods from members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), with reductions on another 15 percent phased in over a 10-year period. For countries such as Japan and South Korea, with which India already had trade agreements, the reduction would be on 62.5 percent of items. The rest of RCEP members, including China, which doesn’t currently have a free trade agreement with India, would have received a reduction on 42.5 percent.

India and CPEC

CPEC not only passes through Indian territory of Baltistan Gilgit, it also passes through PoK. Heavy Chinese security presence, over one Division (10,000 troops) in the pretext of guarding the corridor has implications. Pakistan becomes more indebted to China. If it cannot pay back debt, they may back in sovereignty, allowing China greater political and security control. This has already happened with a very long term lease of the strategic Gwadar port. All this has security implications for India, and creates conditions favourable to a two front war. Also in hope of Chinese backing, Pakistan can become somewhat over confident and may take some fool hardy steps on the border in Jammu and Kashmir. Though could also step up terror attacks.

CPECChina’s “Inroads” – Security Implications India

Adequate timelines have been set to achieve targets, such as completing the mechanisation and full modernisation of the PLA by 2020, emerging as a socialist modernized country by 2035, having a world-class army and the eventual attainment of super power status around the middle of the century. India is immediately concerned with some aspects of the BRI. Success of BRI takes China closer to becoming a super power and it then would increase hegemony in the region. Of major concern is the CPEC in Pakistan which not only passes through disputed with India Gilgit-Baltistan region, but it brings China and Pakistan strategically closer. Corridor also passes through Baluchistan which has a strong independence movement. Also it brings Chinese boots on the ground in Pakistan. Currently it is estimated that nearly 10,000 Chinese troops are in Pakistan in the garb of securing CPEC projects. This also increases the prospects of a two-front war with India. China’s road infrastructure projects in Nepal and Myanmar are of concern to India as they tend to impact India’s influence in the region. The maritime silk route passing through Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka and going through some other ports in the Indian ocean has implications for India. China intends to cover all routes to Africa and middle east Asia. Chinese investments in Iran are already affecting the Iranian interest in Chabahar Port. China’s interests around India are less economic and more security related. India with world’s largest population and old civilisation could be the only country that can slow the pace China’s world dominance.

Options India

Different approaches have been suggested for India to counter China’s strategic BRI. Some have suggested that India could derive greater benefit from joining it. Most are of the view that we need counters to BRI through home-grown Indian initiatives. India’s approach could be bilateral, and unlike China’s with no geo-political strings or arms twisting involved. India could work with other countries in the region who are affected by the Chinese hegemony and belligerence. Meanwhile, US President Donald Trump has been making attempts to convince India to join its ambitious plan to counter China’s ‘Silk Route’ program of port and highway constructions. The US, Japan and Australia unveiled the ‘Blue Dot’ infrastructure network, ostensibly to certify and promote infrastructure development, but in reality, it was to take on China’s BRI. The Western alternative has been in the making for some time as nations have voiced alarm at the cheque-book diplomacy of China through its BRI projects and their security ramifications.

The US launched the “Blue Dot” pointing out that American direct investment into Asia had topped $1.6 trillion and that “our numbers will only get bigger”. The Blue Dot could be backed with funding by Japan’s JICA and America’s newly founded International Development Finance Corporation and Ausaid, not to mention a host of global development finance windows backed by the West. China’s overseas projects funded by debt from its own infrastructure banks are now viewed with trepidation, by both recipient countries for the potential debt trap that these projects could push them into as well as by nations like the US and India who see them as potential international security bases from which the People’s Liberation Army and Navy could operate. India itself has been struggling to complete its own bits of the Asian highway program that would link its Northeast with Myanmar and Thailand, even as it finds it tough to compete with China in Africa with smaller road, port and railway projects. India’s problem is not just a funds crunch that the Americans and Japanese could help solve, but also a capacity issue where its builders and railway men have as yet just not been able to compete with China’s efficiency and huge construction capacity. India should take steps to address these issues. For India has a significant domestic market and unlike China, it is not dependent so heavily on exports. Yet becoming an exporting nation is important for overall economic development. The Debt trapped BRI is likely to implode at some point. India must build efficient internal manufacturing strength by evolving cheaper high quality solutions. India is already concentrating a great deal on its infrastructure projects including road, rail and waterway projects. The same need to be accelerated. On BRI, it is best to wait and watch.