Down on the Biden economy …… Down Down Down

By James K. Galbraith

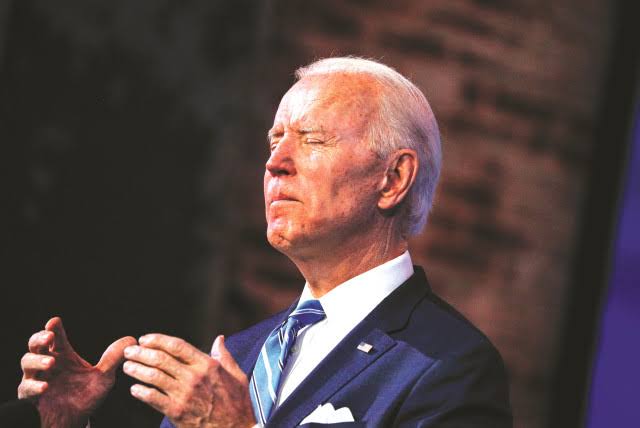

In a recent CNN interview, Paul Krugman of The New York Times finds it hard to understand why ordinary American voters do not share his euphoric view of US President Joe Biden’s goldilocks economy – which appears to be neither hot nor cold. Inflation is falling, unemployment remains low, the economy is growing, and stock market valuations are high. So why, Krugman asks, do voters give Biden’s economy a lousy 36 percent approval rating?

Journalist Glenn Greenwald sees class bias in Krugman’s wonderment: as though Krugman were just another pampered rentier with ample cash, real estate, stocks, and bonds. But this is most unfair. Though I have not been to Krugman’s home, I have seen his ultra-modest office at the City University of New York. He’s certainly done well, but I suspect his plebeian tastes have changed little since his junior faculty days at Yale, when I was a graduate student there.

Unlike unemployment, inflation does affect everyone. But what matters to working people is not the monthly or yearly price change taken alone. What matters is the effect on purchasing power and living standards over time.

No, Krugman’s problem is not too much money. It’s the obsolescence of his ideas. He and I came of age, professionally, during Jimmy Carter’s presidency. Republicans, gunning for Carter, availed themselves of the “misery index,” a measure comprising the sum of the unemployment and inflation rates in a given month or year. As a polemical device, the index was devastating, especially in 1980, when Carter’s credit controls caused a short recession, just after the Iranian Revolution’s shock to oil prices. Ronald Reagan rode to the presidency on that horse.

Today, with inflation and unemployment both running between three and four percent, the misery index is low. Back in the 1970s, those in power would have been thrilled. Mainstream economists would have been perplexed, and that hasn’t changed. They were in thrall to something called the Phillips curve – or worse, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment. To this day, some of them still can’t figure out why low unemployment doesn’t cause high inflation. That is why they marvel when the misery index is low – as Krugman does today.

The misery index was never more than a headline number. Dig beneath the surface, and one finds that its two components are not as relevant to ordinary people as the pundits appear to think. Even when the unemployment rate is relatively high, it has never – apart from the Great Depression or the pandemic shock – directly affected more than a small share of the workforce at any given time. People don’t like recessions, but even in bad times, most people keep their jobs.

Unlike unemployment, inflation does affect everyone. But what matters to working people is not the monthly or yearly price change taken alone. What matters is the effect on purchasing power and living standards over time. Whether these are rising or falling depends on the relationship of prices to wages. When wage growth exceeds price increases, times are generally good. When it doesn’t, they aren’t.

It is here that Biden has a problem. During his presidency, living standards have not risen. From early 2021 to mid-2023, prices have increased more than wages, implying that real (inflation-adjusted) hourly wages and real weekly earnings have fallen, on average. Not by much, but they have fallen. Worse, the average figure probably masks a larger fall, in real terms, for families that started out below the average. And given how income distributions work, there are always many more families earning less than the average than there are who earn more.

American households used to be able to offset stagnant real earnings by adding workers and jobs per household. Although those extra jobs usually were not very good, the process of extending work to women and young people helped families maintain their living standards despite the vast decline in high-wage manufacturing jobs. That was true, to a large degree, in the late 1980s and in the 1990s when many women, young people, and minorities entered the workforce.

But this process has petered out. Though the employment-to-population ratio is up a bit since early 2021, it is still below where it was in 2019. Meanwhile, with the end of pandemic relief policies, the US savings rate has dropped from a robust 20.4 percent of earnings in early 2021 to an anaemic 3.5 percent. Krugman sees that number as an indication that people are spending confidently, but it is much more likely a sign of stress.

No wonder Biden’s economic approval rating is so low. It will likely remain there until American voters start to see better results in their own pockets. Most people are not moved by pundits babbling about how great things are. Krugman and cable news are not going to change people’s perceptions, especially if they suspect – rightly – that many rich Americans are doing much better than they are.

In this context, and with another election coming up, it seems unwise to tell American workers that they have never had it so good. In fact, as a political matter, such arguments have never worked. Perhaps Krugman, who went to work for Reagan back in 1983, has forgotten the devastating question that his old boss posed during a 1980 debate against Carter: “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?”