From sniffer dogs to sewage testing, scientists are finding new ways to detect COVID-19

Right now if we want to know how many people have COVID-19, we have one primary tactic: individual testing.

It’s resource-intensive, inconvenient — and hamstrung by the notion that everyone will have symptoms and act on them.

So with the World Health Organisation warning there may never be a “silver bullet” for COVID-19, scientists are investigating more creative tactics to keep tabs on the virus.

Enter dogs, drones and sewage testing.

Let’s take a look at how Australian researchers are exploring these less traditional tracing systems and how close we are to implementing them.

Canine disease detectives

Freya is being re-trained to detect COVID-19 in the UK. Here she is correctly identifying a positive sample of malaria.(Getty: Leon Neal)

In just a couple of months, the first Australian detection dogs will be fully trained in how to detect the odour of COVID-19.

Dogs’ powerful sense of smell has already been used to sniff out cancer and Parkinson’s disease. Initial research conducted in France shows they can also reliably recognise someone with COVID-19.

They do this by smelling what’s known as COVID-19 Volatile Olfactory Compounds (VOCs), emitted through human sweat. VOCs are produced by your body all the time but their smell changes ever so slightly if you are positive for COVID-19.

And don’t worry, you don’t have to be sweaty, or even that close, for the dogs to pick up on it.

Anne-Lise Chaber, a veterinarian and expert in disease detection at the University of Adelaide, said some dogs have shown 100 per cent accuracy.

“Say someone is sitting and the dog is put next to them, the dog will sit if they are positive,” she said.

“Importantly, you don’t even need to have any symptoms for them to smell you and this is critical as we know many people with COVID-19 have no symptoms.”

A labrador is trained to smell COVID-19 at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

The study from the National Veterinary School in Alfort, France suggested sniffer dogs could be an excellent tool for this virus because they rarely miss positive cases and return a low rate of false positives.

So far, breeds like German shepherds and labradors have shown the most success but research is ongoing about which breeds are better than others.

Dr Chaber says her team is waiting on sweat samples from positive patients in Australian hospitals before they start training with dogs in Victoria, SA and NSW.

“We are preparing everything and will start very, very soon.”

Dogs who have already been trained in smell detection, like firearm dogs, take about six to eight weeks to train for COVID-19 detection while “green” dogs with no prior experience take a few months.

Dr Chaber envisions sniffer dogs being used in airports and aged care homes across Australia. She says they would be a great option to screen health care workers on a daily basis.

In the United Arab Emirates, COVID-19 detection dogs have already been deployed in airports and hospitals.

All that is flushed

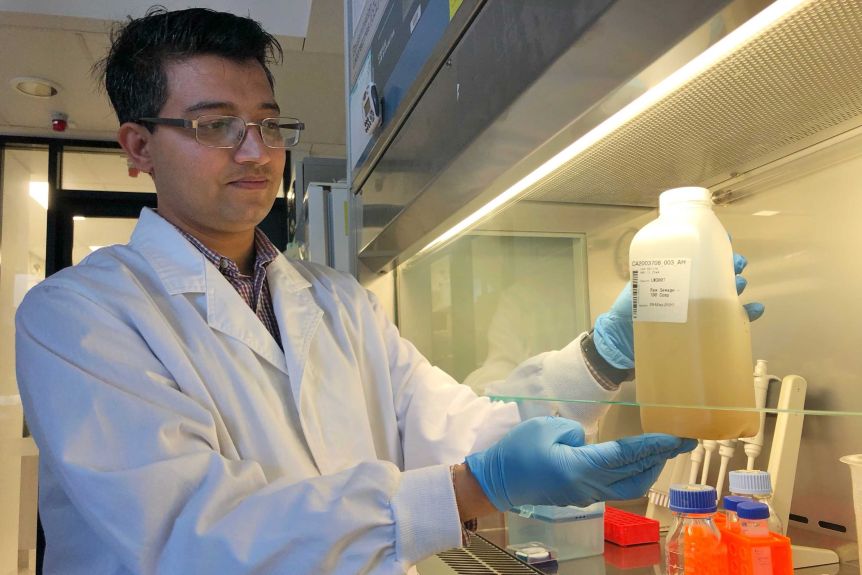

A laboratory technician in Canberra tests a sample of sewage for traces of COVID-19 in July.(ABC News: Ian Cutmore)

Every time you use a toilet for a number two, you are technically helping health authorities find out where COVID-19 is.

Research from the Netherlands found people infected with COVID-19 shed viral material in their faeces and Australia is already starting to tap into that data flowing through our toilets.

It’s cheap and convenient — and pathogens can appear in stools within just three days of infection, which is far earlier than symptoms generally appear.

If you’re wondering why a respiratory disease would show up in this way, scientists say it’s just another example of COVID-19 not behaving like a simple respiratory virus.

The gastrointestinal system is considered an alternative route of infection as the virus goes looking for its favourite cell receptors. This means that up to half of all infected individuals shed virus through their faeces.

Many parts of Australia are doing their own sampling and analysis including Victoria, Queensland, ACT, SA, WA.

Just last week NSW alerted the community to the presence of COVID-19 in sewage from the Perisher Valley.

Wastewater systems are each state’s responsibility and there is no national scheme to date, but Water Research Australia is leading a nation-wide program which feeds back data to health authorities.

There are two major pitfalls of this kind of testing: it doesn’t tell us how many positive cases there are in an area (just that there is at least one) and it may pick up pathogens from someone who is actually recovered but still shedding.

For example, Australian researchers who recently analysed wastewater from a flight found COVID-19 in the sewage, but subsequent nasal swabs of passengers returned no positive results.

So this kind of testing is best used as an early-warning system to identify emerging outbreaks and help inform decisions about restrictions.

The CSIRO, which is leading research in this area, says sewage testing even has the potential to give results on a suburb-by-suburb scale.

Surveillance from above

If you don’t want to think too much about the sewers, turn your eyes to the sky: ‘pandemic drones’ might also join the fight in the future — although in this case, there are quite a few obstacles still to overcome.

Researchers at the University of South Australia are developing software so drones can monitor temperature, heart and respiratory rates as well as detect people sneezing and coughing.

It’s not easy work and many of the public aren’t particularly comfortable with the idea, says team leader Professor Javaan Chahl.

“It’s pretty hard to develop this kind of signal processing. The major issue is continuous movement … and changes in light levels.

“We’ve had a team of six people working five days a week for a couple of months to get it working.”

The plan would be to move any collected observations to a secure cloud and then have health authorities process that information.

Professor Chahl says the software isn’t trying to recognise individual people, just to spot tell-tale signs of the virus.

So could we see COVID-19 drones over our heads anytime soon?

“It’s a question of what will people tolerate. The technology is working but the ethical, legal framework for how you do it is not in place,” Professor Chahl says.

“It seems people are unhappy with the idea of deploying this … and we don’t want to be bad guys.”

The research team’s industry partner, Draganfly (a US drone tech company), is working closely with the US and Canadian Governments but Professor Chahl says not many conversations have taken place yet in Australia.

“That’s because up until a few weeks ago, when the second spike in Australia really became obvious, we didn’t have a crisis of the same scale.”

Drone monitoring is also difficult to use in conjunction with many health mandates, like lockdowns (because there is no one out in public to screen) or face masks (which make detection of symptoms difficult).

“Although we have this working, the question is what to do next with it,” says Professor Chahl.