Global media, politics behind Liberation War

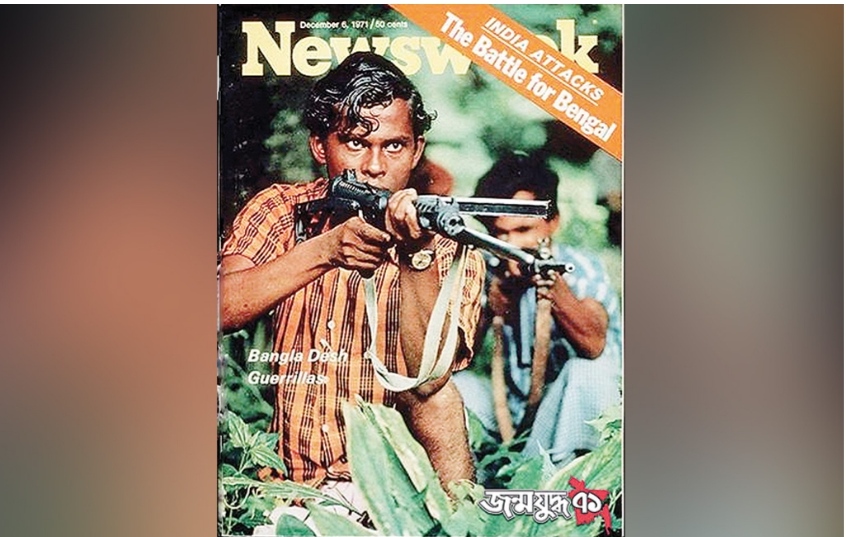

A Newsweek magazine cover on 1971 Liberation War Courtesy

Awami League chief Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared the independence of Bangladesh just before the operation was launched and was arrested

The 1971 Liberation War was the result of a long-cherished dream of the Bengalis in then East Pakistan to taste freedom. It took them two decades to get the People’s Republic of Bangladesh by getting rid of the Pakistani occupation forces.

Dubbed the most crucial period in the birth of Bangladesh, the war saw large-scale atrocities – a genocide that claimed over three million lives, the exodus of 10 million refugees, internal migration of 30 million people and massive destruction of properties – in only nine months. The war broke out just before midnight on March 25, 1971, when the Pakistani army launched a crackdown called “Operation Searchlight” against the Bengali civilians, students, intellectuals and armed personnel, who were demanding that the military junta accept the results of the first democratic elections in Pakistan in 1970 won by the Awami League.

Awami League chief Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared the independence of Bangladesh just before the operation was launched and was arrested.

The Pakistan army engaged in a systematic genocide and atrocities of Bangali civilians, particularly nationalists, intellectuals, youth and religious minorities. During the Liberation War, broadcasting station “Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra” played a crucial role in inspiring the guerrilla fighters and supporters of freedom.

While the freedom fighters fought the Pakistani occupation forces on the battlefields, the artists of the radio station joined another kind of war by keeping the hope of freedom alive among millions.

Notably, the role the international media played during the war is priceless. The London Times, the Sunday Times, The Guardian, The Sunday Observer, The Daily Mirror and The Daily Telegraph were helping in disseminating the news of the genocide and expediting cooperation among the international community to support Bangladesh.

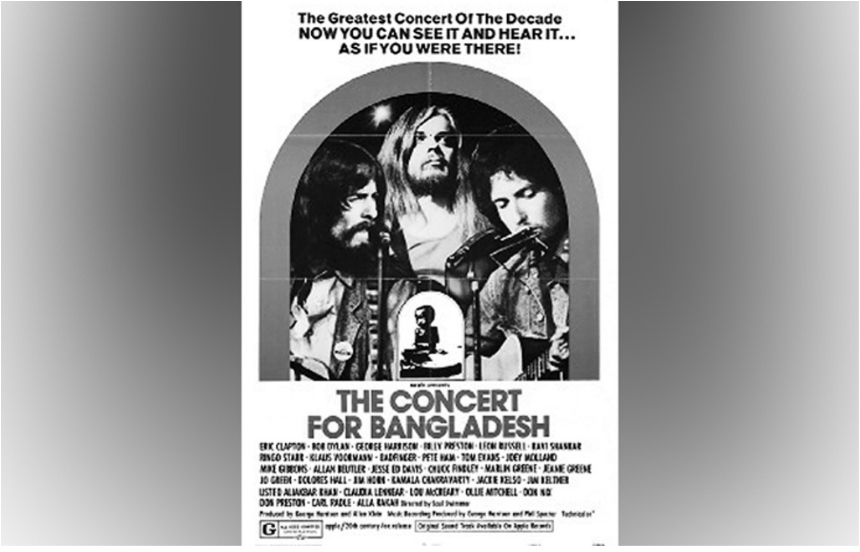

The story does not stop there; some artists, too, shared their sympathy for the subjugated people of the newly-born country. The concert for Bangladesh, which garnered much international awareness, was organised by Pandit Ravi Shankar and George Harrison in New York in August 1971. It was the first-ever benefit concert of such a magnitude and featured a super-group of performers that included Harrison, fellow ex-Beatle Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Leon Russel and the band Badfinger. In addition, Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan, both of whom had ancestral roots in Bangladesh, performed an opening set of Indian classical music. Shankar said: “In one day, the whole world knew the name of Bangladesh.”

The poster of The Concert for Bangladesh | Courtesy

International politics

The two superpowers, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the US, which dominated a largely bipolar world until the mid-1980s, played a significant role in the Liberation War. Shockingly, the UN took no action to stop the genocide in Bangladesh. The people of Bangladesh fought for their liberation at the height of the cold war. Among the five permanent members of the Security Council, the US and China directly supported Pakistan, the Soviet Union stood for Bangladesh, while the UK and France, despite showing sympathy for Bangladesh, could not openly challenge the US, and hence, abstained from voting. This deep division among the permanent members of the UN Security Council completely paralysed the Security Council.

India played a significant role in favour of Bangladesh. When Pakistan declared war against India on December 3, 1971, India directly entered the Liberation War. It followed the Pakistani pre-emptive airstrikes in northern India. On December 16, the allied forces of Bangladesh and India defeated Pakistan in the East.

The role of Soviet Russia

The response of the Soviet Union was conditioned by the general Soviet policy with regard to Asia in the 1960s. It was a policy of growing involvement, initially undertaken to contain US influence in Asia, but increasingly directed at stemming the diplomatic and military as well as ideological advance of China which at that time was emerging as the Soviet Union’s principal rival in the Third World.

The Soviet Union’s close ties with India were vital in shaping the Soviet response towards the Liberation War. The relatively high priority given by the Soviet policymakers was the consequence of their perception of the contemporary world and Asia, and the proper Soviet role in both the world and Asian dimensions as a great power. Thus, behind all that happened in the sub-continent over the 1971 Bangladesh struggle “was a power struggle between China and the Soviet Union and a strategic conflict between Moscow and Washington.” In South Asia during December 1971, the Soviet Union seemed to have gained most from this three-cornered fight.

US stance

The US played a more complex and somewhat negative role in the war. Nevertheless, it should be noted that American society’s response was one of positive support, contradicting the state’s negative role. In the pluralist and open society of the US, influential and articulate segments stood solidly behind the cause of Bangladesh. As the crisis developed, the American response went through several discernible phases.

The first phase of quiet non-involvement began on March 25 and lasted roughly until July 8, 1971. During this phase, the US posture was “neutral” and it described the problem in Bangladesh as Pakistan’s “internal matter.”

The second phase started with the secret trip by President Nixon’s National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger to China on July 9-10, 1971. This marked the real beginnings of Sino-US detente and led indirectly to the formalisation of the Indo-Soviet alliance by a treaty in August. During this phase, which lasted until September, the US pursued diplomacy of restraint, counselling India to desist from armed conflict with Pakistan and privately pressing Pakistan to thrash out a “political settlement” of the East Pakistan issue.

During the third phase, lasting from September until December 3, when the Indo-Pakistan war over Bangladesh broke out, the US attempted to promote a constructive political dialogue between the Pakistani military government and the Bengali nationalist leaders in India, but in vain.

The fourth phase covered the period of the Indo-Pak war. During the 14-day sub-continental war, the US-backed Pakistan and blamed India for the escalation of hostilities, and tried through the UN and other means to bring about a ceasefire and “save West Pakistan” from possible Indian attempts to destroy it militarily.

President Nixon ordered a task force of eight naval ships, led by the nuclear aircraft carrier Enterprise, to sail into the Bay of Bengal in a “show of force.” In response, On December 13, Russia dispatched a nuclear-armed flotilla, the 10th Operative Battle Group (Pacific Fleet) from Vladivostok. Russia deployed two task groups; in total two cruisers, two destroyers, six submarines, and support vessels. A group of Il-38 ASW aircraft from the Aden airbase in Yemen provided support.

How international media acted

The Liberation War was fought not only by the brave Mukti Bahini within Bangladesh but also supported through the coverage it received in the international media and artists. Journalists brought home to the people of the world the stories of the trials and sacrifices of the heroic people of Bangladesh, and the tribulations they were facing under the insensitive and brutal military administration of the occupying armed forces of Pakistan.

On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani military forcibly confined all foreign reporters to the Hotel Intercontinental (currently the Rupashi Bangla) in Dhaka, the night the military launched its genocide campaign. The reporters, however, saw tank and artillery attacks on civilians through the windows.

Two days later, as Dhaka burned, the reporters were expelled from the country – their notes and tapes were confiscated. One of the expelled reporters was Sidney Schanberg of the New York Times. He would return to Dhaka in June 1971 to report on the massacres in towns and villages. He would again be expelled by the Pakistan military at the end of June.

Two foreign reporters escaped the roundup on March 25. One of them was Simon Dring of the Daily Telegraph. He evaded capture by hiding on the roof of the Hotel Intercontinental. Dring managed to extensively tour Dhaka the next day and witness first-hand the slaughter that was taking place. Days later he left East Pakistan with his notes. On March 30, 1971, the daily published his front-page story of the slaughter in Dhaka that the army perpetrated in the name of “God and a united Pakistan.”

In April 1971, the Pakistan army flew in eight reporters from West Pakistan for guided tours with the military. Their mission was to tell the story of normalcy. The reporters went back to West Pakistan after their tour and dutifully, filed stories declaring all was normal in East Pakistan. However, one of the reporters had a crisis of conscience. This reporter was Anthony Mascarenhas, the assistant editor of the West Pakistani newspaper The Morning News.

On May 18, 1971, Mascarenhas flew to London and walked into the offices of The Sunday Times offering to write the true story of what he had witnessed in East Pakistan. Upon agreement from The Sunday Times, he went back to Pakistan to retrieve his family. On June 13, with Mascarenhas and his family safely out of Pakistan, The Sunday Times published a front-page and centre page story titled “Genocide.” It was the first detailed eyewitness account of the genocide published in a western newspaper.

In June 1971, under pressure and in need of economic assistance, Pakistan allowed a World Bank team to visit East Pakistan. The team reported back that East Pakistan lay in ruins. One member of the team reported that Kushtia looked “like a World War II German town having undergone strategic bombing attacks” as a result of the Pakistani army’s “punitive action” on the town. He also reported that the army “terrorises the population, particularly aiming at the Hindus and suspected members of the Awami League.” The then World Bank president, Robert McNamara, suppressed the public release of the report. It was leaked to the New York Times.

Despite the Pakistani military’s best efforts to hush up the truth about their genocide campaign against Bangalis, reports filtered out of East Pakistan to the outside world – thanks in part to the efforts of determined foreign reporters. Following are the foreign newspaper reports from the beginning of the genocide in March 1971 to its end. They chronicle the bloody birth of Bangladesh.

Source: Dhaka Tribune