Has a ‘gold rush’ mindset blinded Australian businesses pursuing ‘mercurial’ China market?

By

Daniel Mercer and Jon Daly

Shanghai, where signed contracts “are just the start of negotiations”.

It was in the mid-2000s during a regular meeting with a client that Bob Cronin realised he’d grossly underestimated the challenges of doing business in China.

Key points:

- A veteran trader says Australian exporters have ignored sovereign risk in dealing with China

- Federal Labor says “frenzied” and “irresponsible” language about war has to end

- There are claims China is “running out” of Australian industries to hit with sanctions

They were heady days in the bilateral relationship between Canberra and Beijing when the sky seemed the limit for enterprising Australians in the Middle Kingdom.

Yet the veteran newspaperman got a harsh reality check not long into his stint editing the Shanghai Daily, the English language Chinese journal then part-owned by Australian billionaire media proprietor Kerry Stokes.

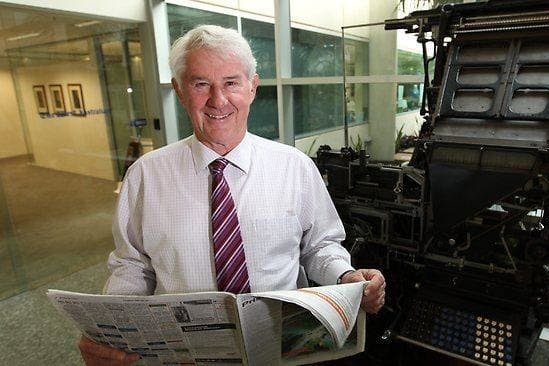

“We had an advertising contract with a company,” Mr Cronin, a former editor-in-chief of The West Australian, said.

“The deal was that they agreed to pay us x dollars a month.

“In return for that, they had the right to sell advertising in the Shanghai Daily.

Former Shanghai Daily editor Bob Cronin says Australian businesses often “blunder” into Chinese dealings.

“So you say, ‘You have to pay us $100,000 a month … if you sell $150,000 of advertising in the paper you make $50,000 … if you sell $80,000 of advertising, you lose $20,000’.

“That was the deal. That was the contract.

“And after about six months they came back and said: ‘Advertising is much harder than we thought and so we need to change the contract’.”

Despite efforts to rebuff the request, Mr Cronin said he was soon giving in to the demands when it became obvious that attempts to enforce the contract would be futile.

“It was during all that unpleasantness that someone said to me: ‘You’ve got to understand, in China, that the signing of the contract is the start of the negotiations’.”

China dream a ‘dangerous mindset’

While just a snapshot of the challenges facing Australian businessmen and women in China, experts say it highlights the pitfalls that can exist when dealing with our biggest trading partner.

Nick Hunt helped establish several Australian businesses in China.

Nick Hunt is a WA-based trader who helped set up the Chinese operations of some of Australia’s biggest agribusinesses, including ASX-listed Elders and Nufarm, as well as those owned by billionaire Andrew Forrest.

After spending much of the past 30 years living and working in North Asia, he said he’d come to the view that many Australian businesses had been blinded by greed and “reckless indifference” in their pursuit of the China “gold rush”.

“I think the dream, if we’ll call it that, has always been a dangerous mindset to have,” Mr Hunt said.

“Sovereign risk in dealing with China, in my view, has always been the biggest issue in dealing with China.

“China is a mercurial market to deal with and a risky market to deal with.

“We should have known there would be ups and downs in the relationship.

“I think that a lot of exporters have been blind to the harsh, cold realpolitik of dealing with China.”

Difficulties in trading with China have been thrust into the spotlight again this month on the first anniversary of Beijing’s strike against Australian barley producers.

Diplomatic relations between Canberra and Beijing have been sliding steadily in recent years.

Risks laid bare in trade fallout

The imposition of 80 per cent tariffs last May set off an alleged campaign of economic coercion that included hits to beef producers, winemakers, coal miners and lobster fishers.

But a year on, trade experts have cast doubt on the effectiveness of Beijing’s tactics amid claims that affected industries have largely offset any losses by finding new markets.

Regardless, shadow trade minister Madeleine King said the fallout between Canberra and Beijing had come at a real cost for many Australian businesses and families.

Shadow trade minister Madeleine King says Australia needs a “clear eyed” strategy for China.

Ms King cited the example of lobster fishers, many of whom faced going to the wall after China’s decision to suspend trade sent prices crashing.

She said while federal Labor opposed China’s actions and supported many of the decisions taken by the Morrison Government on national security grounds, such as excluding Huawei from the 5G roll-out, the Coalition had got the balance wrong.

“We’ve seen the ramping up of discussions around security interests,” Ms King said.

“And that’s fine in the context of a more outward looking and more aggressive China.

“But, equally, it’s the economy, stupid.

“We’ve got to have a clear mind around our economy as well and how that interacts with security interests.”

Calls to end ‘frenzied’ language

What’s more, Ms King called for an end to “frenzied” and “irresponsible” rhetoric from politicians and senior officials towards China.

“What we see is a strange pile-on of the language,” she said.

“There’s a difference between being responsible and irresponsible in terms of freedom of speech and I think seeking to whip up anti-China sentiment for base political purposes should stop in this country.”

The value of Australia’s iron ore trade to China has never been greater.

Even as targeted industries divert their goods to other markets, the value of China to Australia’s bottom line has been laid bare in the past fortnight.

This month, Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg revealed a major improvement to the nation’s finances partly on the back of higher iron ore prices, while it emerged this week WA was set to post a world-beating $5 billion surplus for 2020-21, courtesy of a royalty windfall.

China ‘running out of trade targets’

Perth USAsia Centre research director Jeff Wilson said there was little doubting the consequences that would flow if Australia’s iron ore trade with China was disrupted.

But Mr Wilson said that Beijing’s “self-interest in leaving iron and gas alone” meant Australia would be in a relatively strong position for the foreseeable future.

“The fact that China is now sanctioning very small products — tens of millions of dollars of a fruit here or there – is a function of the fact that all the big things … have already been subject to sanction,” Mr Wilson said.

“And so my prediction would be that this has probably reached its logical conclusion, simply because there are no large targets left to hit.

“China has run out of ammunition in a trade war with Australia.”