India – China Disengagement : Implications And Road Ahead

By

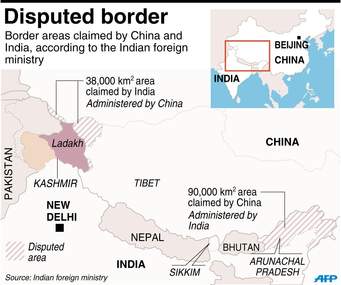

China illegally occupied approximately 38,000 sq Km in the Union Territory of Ladakh, mainly during the 1962 conflict. In addition, under the so-called Sino-Pakistan ‘boundary – of 1963, Pakistan illegally ceded 5,180 sq km of Indian territory in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir to China. Thus, China is in illegal occupation of more than 43,000 sq km of Indian territory. China also claims approximately 90,000 sq km of Indian territory in the eastern sector of India – China boundary in Arunachal Pradesh. India has never accepted this ‘illegal occupation’ of our territory or the ‘unjustified claims’. India’s consistent stand has been that while bilateral ties can develop in parallel with discussions on resolving the boundary issue, any serious disturbance in peace and tranquillity along the LAC is bound to have adverse implications for the direction of overall relationship. The Chinese side is well aware of our position. The boundary between India and China is not demarcated on ground and is defined by Line of Actual Control (LAC) in which both the countries have different perceptions regarding the alignment. More often than not, patrols of either country’s army have intruded into each other’s territory and at times clashed with each other physically.

Chinese Intrusion

In Apr 2020, China marched into areas of Indian territory to unilaterally change the status quo along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in its favour, exploiting its advantage to move first in the garb of a military exercise. The Chinese had mobilised a large number of troops and armaments along the LAC as well as in the depth areas. In Depsang and north of Pangong Tso lake, the Chinese military built several bunkers and other structures in these areas. The Chinese had blocked all Indian patrols beyond Finger 4 till Finger 8, triggering strong reaction from the Indian Army. It expected that India would accept nominal disengagement, while Chinese troops would continue to be sitting in Depsang, Finger 8 to Finger 4 and some other areas. A gross miscalculation indeed.

Indian Reaction

India responded quickly, displaying its national resolve to deal with the emerging situation proactively. Our armed forces too had made adequate and effective counter deployments in these areas to ensure that India’s security interests were fully protected. On 14 Jun 2020, while the disengagement process was going on in Galwan valley, the troops of the two armies clashed with each other with sticks and rods that led to the death of 20 Indian soldiers and probably 45 Chinese soldiers(unconfirmed). A sad incident indeed. The Indian army displayed its grit and determination to take on the Chinese army’s unilateral attempt to change the LAC and honoured its brave soldiers with gallantry awards sending a clear message that Chinese action was taken as an act of war.

In end August 2020, our armed forces had responded to the challenges posed by the unilateral action of the Chinese army and occupied strategic positions on Kailash Range, south of Pangong Tso Lake, before the Chinese could take advantage of the area. A small exchange of fire took place between the two armies, sending a stern message to the Chinese army that India will not tolerate unilateral change in status quo of the LAC and that it can also act proactively to occupy the strategic dominating heights. With the pre-emptive occupation of Kailash range by the Indian army, the Chinese deployments on the south of Pangong Tso had become very vulnerable.

Both the armies built up their strength to nearly 50,000 troops and continued in eye ball to eye ball contact for the entire winters. The Indian armed forces deployed their Airforce, tanks, mechanised Infantry, guns, surveillance systems to keep a check on the Chinese troops. Similar build-up of forces also continued on the Chinese side. The stalemate continued till Feb 2021, with both armies in eye ball to eye ball contact, without firing a single shot. The continued stalemate was not in the interest of the Chinese armed forces which always presented itself as invincible. Therefore, the Chinese initiated a disengagement agreement to break the stalemate.

China- India Disengagement Agreement

Earlier eight rounds of military and diplomatic level talks between the two countries had not yielded any fruitful results as both the parties had stuck to their respective positions. India insisted that all troops be moved to pre-April 2020 positions, while China insisted move back to pre- August 2020 positions.

With the level of trust deficit between the two countries, Chinese know that any pull back without a mutual agreement can lead to Indians occupying some important features vacated by them. After the ninth round of military level talks between India and China, a consensus was reached between the two countries to break the stalemate and de-escalate the situation along the borders in Pangong Tso lake area. Thus, the Indo -China disengagement pact was concluded.

Under the India-China disengagement pact in eastern Ladakh, the Chinese army will pull back its troops from Finger 4 to Finger 8 in the northern bank of Pangong lake. Reciprocally, Indian troops will be based at their permanent post near Finger 3. The areas between Finger 3 and Finger 8 will become a no patrolling zone till further resolution is reached by both sides. Similar action would be taken in the south bank of Pangong lake by both sides. This means that Indian troops will vacate number of strategic heights at the southern bank of Pangong lake in Kailash range and structures that had been built by both sides since April 2020 will be removed. These are mutual and reciprocal steps being taken by both sides to restore the pre-April 2020 positions. Later similar actions to de-escalate the situation would also be undertaken in other areas of conflict.

Implications

Firstly, Defence Minister, Rajnath’s speech in the parliament disclosing the disengagement agreement with China, clearly indicates that Indian politicians are no more afraid to openly slam China for its occupation of Indian territory and occupation of Tibet. Indian Government’s decision to honour those killed in Galwan clash with gallantry awards imply that India considers Ladakh incursions as an act of war. This time Government of India has not only portrayed China as aggressor but has also clearly brought out that China is in illegal occupation of Tibet and Ladakh.

Secondly, after Doklam, Galwan and Naku La skirmish in Sikkim, the rest of the world has seen that Chinese are not that invincible as they like to think of themselves. A determined India has the capability and capacity to stop their expansionist tendencies. India has achieved its political aim where it has proved to the world that China cannot impose hegemony over India by intruding into its territory and prevent infrastructure development on the Indian side which threaten Aksai Chin/ other areas. Both sides continue to develop the infrastructure in their perceived side of the LAC.

Thirdly, China has shown the world that India is not in a position to clear the Chinese intrusions and so has India shown that its occupation of Kailash Range cannot be challenged by China. China is wary of even a limited war lest the untested PLA suffers a set a setback. Even if India is able to force a stalemate, it would be a setback for superior China. Hence, China will prefer to retain the gains made by it without too many concessions.

Fourthly, it is clear that neither side seems to prefer war. Despite face-to-face deployment of troops, no casualties have taken place since the Galwan valley incident in Jun 2020. The last exchange of fire took place in early September, after India secured Kailash Range. On 20 Jan 2021, Chinese again attempted ingress in Naku La, in Sikkim, which was challenged and successfully thwarted by the Indian troops after a small skirmish.

Fifthly, India was taken by surprise when the Chinese intruded and occupied the territory in Depsang plains and north of Pangong Tso. India’s image as an emerging power was severely dented. However, it recovered the lost ground when it was able to beat China in occupation of Kailash range in end Aug 2020. India’s political aim is to restore pre-April 2020 positions and demarcate the LAC to prevent such illegal occupation by the Chinese in future. India does not have the military capability and the force level to cause a military defeat to China. The strength of the attacker vis-à-vis defender in such high-altitude terrain is 1:12. Neither China nor India can muster such strength to force its decision. Hence, talks are the only way forward to resolve the outstanding issues.

Sixthly, while the start of disengagement involves the troops in contact on the front lines in Ladakh, there remain close to 100,000 troops from the PLA and the Indian Army that were deployed behind the front lines as reserves in case fighting broke out. It is likely that these would only be withdrawn after successful disengagement by the troops in contact. It is estimated that it may take approximately a month to disengage systematically after verification at various stages. It is true that both the countries do not want a repeat of Galwan incident.

Road Ahead

The present disengagement agreement covers only the Pangong Tso Lake sector in the central Ladakh, but makes no mention of Depsang sector, near Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) in Northern Ladakh, where PLA troops have crossed the LAC and established themselves 15-18 km inside the territory that India has always claimed and patrolled. Since April, the PLA has blocked Indian troops from accessing patrolling points 10,11, 12,12A and 13 on the LAC. Indian army regards Depsang as a critical sector, since controlling this would provide the PLA with a springboard to capture DBO, cut off India from the Karakoram Pass, and progress operations towards India’s vital Siachen Glacier sector. Besides Depsang, the disengagement agreement is also silent on the Gogra/Hot Springs sector, where Indian army believes China has encroached Indian territory. It is hoped that disengagement will also take place in these areas subsequently, once the level of trust between the two counties improves.

The 1959 claim line is already well demarcated and so are the buffer zones that lie between it and the existing LAC. Is it possible to find a face-saving conflict resolution for both parties to claim victory and mend the fractured relationship? Finding a diplomatic solution with buffer zones in the intrusion areas where neither side will deploy/patrol/develop infrastructure along with mutually accepted demarcation of the LAC and the buffer zones should be acceptable to both sides. However, caution will have to be taken to prevent any breach of trust common in such situations.

India should not lower its guard and should discretely watch the implementation process on ground. Trust deficit with China will continue for a long time. Even after the troops have withdrawn to pre-April 2020 positions, strong surveillance devices must be deployed to watch the suspicious activities of China along the LAC as well as in depth areas. India should continue to be prepared for ‘two front war’ as a worst-case scenario and continue capacity building accordingly. The modernisation of the armed forces and infrastructure development should continue to take the centre stage, along with economic prosperity. The talks should continue with cautious approach, as a preferred option.

Conclusion

One of the biggest fallouts of the whole Chinese action has been the realisation that China, not Pakistan, constitutes the main threat to India. An entire Indian Strike Corps, along with other formations, has been redirected to LAC as deterrent to Chinese policy along Line of Actual Control. Chinese political aim has always been to have China centric Asia, and forcing Indian subordination is a necessity to achieve it. This aim could not be achieved, despite adventurism in Ladakh. China’s strategic aim was to provide depth to its National Highway to Karakoram Pass and China- Pakistan Economic corridor (CPEC), redraw the LAC as per their perception. This aim appears to have been partially achieved so far. Chinese aim of preventing Indian infrastructure development hasn’t been achieved. Nevertheless, the deal is a good one. It shows that India’s strategy to stand up to China worked.