Iraq’s answer to the pyramids

The Ziggurat of Ur is a 4,100-year-old massive, tiered shrine lined with giant staircases (Credit: Geena Truman)

By Geena Truman

Egypt may have the Pyramids of Giza, but Iraq has the Ziggurat of Ur – an incredibly well-preserved engineering achievement that towers over the ruins of an important ancient city.

Around 4,000 years ago, this pale, hard-packed spit of Iraqi desert was the centre of civilisation. Today the ruins of the great city of Ur, once an administrative capital of Mesopotamia, now sit in a barren wasteland near Iraq’s most notorious prison.

In the shadow of the towering prison fences, Abo Ashraf, the self-proclaimed caretaker of the archaeological site, and a handful of tourists are the only signs of life for miles.

At the end of a long wooden walkway, an impressive ziggurat is nearly all that remains of the ancient Sumerian metropolis.

To get here, I’d been packed into the backseat of a taxi hurtling through the desert for hours, until I began to see the city’s famed monument looming in the distance: the Ziggurat of Ur, a 4,100-year-old massive, tiered shrine lined with giant staircases. A tall chain link fence barricading the entrance and a paved parking lot were the only hints of the modern world.

The very first ziggurats pre-date the Egyptian pyramids, and a few remains can still be found in modern-day Iraq and Iran. They are as imposing as their Egyptian counterparts and also served religious purposes, but they differed in a few ways: ziggurats had several terraced levels as opposed to the pyramids’ flat walls, they didn’t have interior chambers and they had temples at the top rather than tombs inside.

“A ziggurat is a sacred building, essentially a temple on a platform with a staircase,” said Maddalena Rumor, an Ancient Near-East specialist at Case Western Reserve University in the US.

“The earliest temples show simple constructions of one-room shrines on a slight platform.

Over time, temples and platforms were repeatedly reconstructed and expanded, growing in complexity and size, reaching their most perfect shape in the multi-level Ziggurat [of Ur].”The Ziggurat of Ur was built a bit later (about 680 years after the first pyramids), but it is renowned because it is one of the best-preserved, and also because of its location in Ur, which holds a prominent place in history books.

According to Rumor, Mesopotamia was the origin of artificial irrigation: the people of Ur cut canals and ditches to regulate the flow of water and irrigate land further from the Euphrates River banks.

Ur is also believed to be the birthplace of biblical Abraham and, as Ashraf explained while he walked us through the ruined walls of the city, the home of the first code of law, the Code of Ur-Nammu, written around 2100 BCE – 400 years before Babylonia’s better-known Code of Hammurabi.

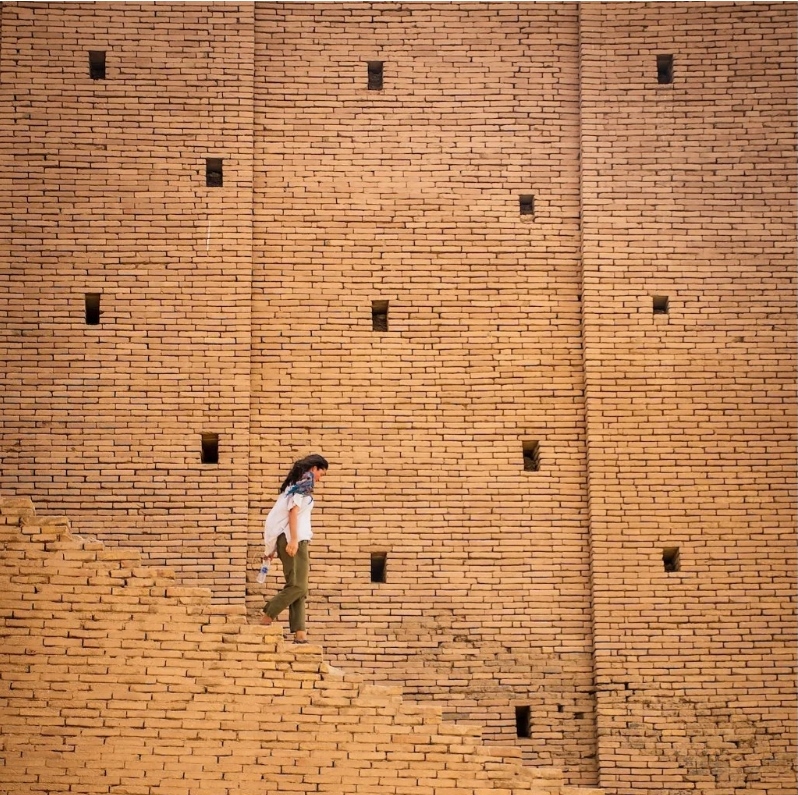

The Sumerians bored hundreds of square holes into the outer walls to allow the internal mud-brick core to stay dry (Credit: Geena Truman)”

In Mesopotamia, every city was believed to have been founded and built as the residence of a god/goddess… who acted as its protector and political authority,” Rumor said.

In Ur, that was Nanna the moon god – for whom the ziggurat was constructed as an earthly home and temple. “The cult of Nanna developed very early around the lower course of the Euphrates (at the centre of which was Ur) in connection with the herding of cows and the cycles of nature that increased the herd,” she said.

The structure’s lower tiers remain today, though the temple and upper terraces at the top have been lost. To figure out what they looked like, specialists have used all kinds of technology and ancient writings (from historians like Herodotus, as well as the Bible).

In her 2016 paper, A Ziggurat and the Moon, Amelia Sparavigna, an archaeological imaging specialist with the Polytechnic University of Turin, wrote, “[Ziggurats] were pyramidal structures with a flat top, with a core made up of sun-baked bricks, covered by fired bricks.

The facings were often glazed in different colours…”.Based on remnants found at the site, it has been generally agreed that the Ziggurat of Ur held a cerulean temple sitting atop two massive mud-brick tiers.

The base alone consisted of more than 720,000 meticulously stacked mud bricks, weighing up to 15 kg each. Reflecting Sumerian knowledge of the lunar and solar cycles, each of the ziggurat’s four corners pointed in a cardinal direction as exact as a compass, and a grand staircase to the upper levels was oriented toward the summer solstice sunrise.

I could see the remains of this great achievement as Ashraf led me and the other few tourists to the main staircase. He knows the site well: he moved here with his father 38 years ago to assist with archaeological digs, and his family home lies just steps from the entrance.

Once I reached the summit, I could imagine the ancient kingdom sprawling out in every direction thousands of years ago.

Each of the ziggurat’s four corners pointed in a cardinal direction, and a grand staircase was oriented toward the summer solstice sunrise (Credit: Geena Truman)

King Ur-Nammu laid the ziggurat’s first brick in 2100 BCE, and construction was later completed by his son King Shulgi, by which time the city was the flourishing capital of Mesopotamia.

But by the 6th Century BCE, the ziggurat was in ruins thanks to the desert’s extreme heat and harsh sand. King Nabonidus of Babylonia set to work restoring it around 550 BCE, but instead of re-creating the original three tiers, he built seven, aligning with other grandiose Babylonian structures of the time, such as the Etemenanki ziggurat, which some believe was the famed tower of Babel.

The bulk of the ziggurat remains intact today largely due to three ingenious innovations by the original Sumerian engineers.First was ventilation. As with other ziggurats, this one was constructed with a core of mud bricks surrounded by an exterior of sun-baked bricks.

And since that core retained moisture that could have led to the overall degradation of the structure, the Sumerians bored hundreds of square holes into the outer walls to allow for quick evaporation.

Rumor explained that without this detail, “the mud-brick interiors could soften during heavy rains, and eventually bulge or collapse”.

Second, the walls were built at a slight slant. This allowed water to flow down the ziggurat’s sides, preventing pooling on the upper levels; the angle made the structure appear larger from a distance, intimidating the empire’s enemies.

Lastly, the temple on top was built with fully baked mud bricks held together by bitumen. This naturally occurring tar staved off water seepage into the unbaked core.

Despite these achievements, by the 6th Century CE, the once-thriving metropolis had metaphorically and physically dried up. The Euphrates River had changed its course, leaving the city without water and therefore uninhabitable.

Ur and the ziggurat were abandoned and subsequently buried beneath a mountain of sand by wind and time.It wasn’t until 1850 that the remains of the ziggurat were found again; later, in the 1920s, British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley led an in-depth excavation of the monument, uncovering what was left of the structure and digging up gold daggers, carved statues, delicate lyres and intricate headdresses from surrounding graves.

But as Ashraf noted, “With only 30% of the site excavated, much more remains to be discovered.”

Ur is believed to be the birthplace of biblical Abraham and the home of the first code of law

Even so, the ziggurat is important enough to have been used as a pawn in modern wartimes.

During the Gulf War in 1991, Saddam Hussein parked two of his MiG fighter jets alongside it, in hopes that the historical site would keep the United States and other foreign nations from attacking his planes.

Unfortunately, the ziggurat still suffered minor damage.

In 2021, Iraq opened its doors to an array of Western countries, and tourism has been emerging slowly (though many governments still advise against travel here).

Janet Newenham, an Irish travel journalist and owner of Janet’s Journeys, visited Iraq shortly after the visa-on-arrival programme launched. Since then, she has led several group tours to the region.

“On our first trip in July 2021, we saw not one other tourist,” she said. “By the time my April 2022 trip came around, we would often meet small groups of adventurous tourists… we never saw more than four or five other tourists at a time though.

Yet nearly every day, Ashraf braves the heat to help tourists understand the importance of the ziggurat. He said he taught himself English by “studying the dictionary” and when most of his foreign visitors were Japanese, he set to work learning snippets of Japanese as well.

As I carefully climbed the grand staircase leading to the flat upper floor, I could still see bits of bitumen between the broken bricks. I also spotted a small, inscribed brick that recognises Saddam Hussein for his partial reconstruction of the monument in 1980.

The upper terraces and the colourful temple have long been destroyed and lost to time.

But across the nearly flat expanse of desert, I could see small mounds scattered throughout the area waiting to be excavated, no doubt hiding a world of treasures yet to be discovered.