Nepal Must Promote Its Unique Niche For Climbing Mt Everest

Raunab Singh Khatri and Rastraraj Bhandari

The southeast summit ridge on the Nepal side of Mt Everest last year, with another border eight-thousander Mt Makalu, and the world’s third highest mountain Mt Kangchenjunga in the distance. Photo JANGBU SHERPA

In 2018 on the 120th anniversary of Peking University, a grand reception was held to celebrate the ascent of Qomolungma by its mountaineering team. With less than two years of training, an amateur team had scaled the world’s highest mountain on the border between Nepal and China.

Wang Yongfeng, vice-chairman of the China Mountaineering Association, “exploring new frontier of China’s amateur mountaineering and outdoor activities”, speculating about the rise of amateur mountaineering.

A year later, China released a tv series Blowing in the Wind on university mountaineering to encourage more expeditions in the coming years, not to mention the growing tourism prospects from the Chinese side of the Himalaya in Tibet.

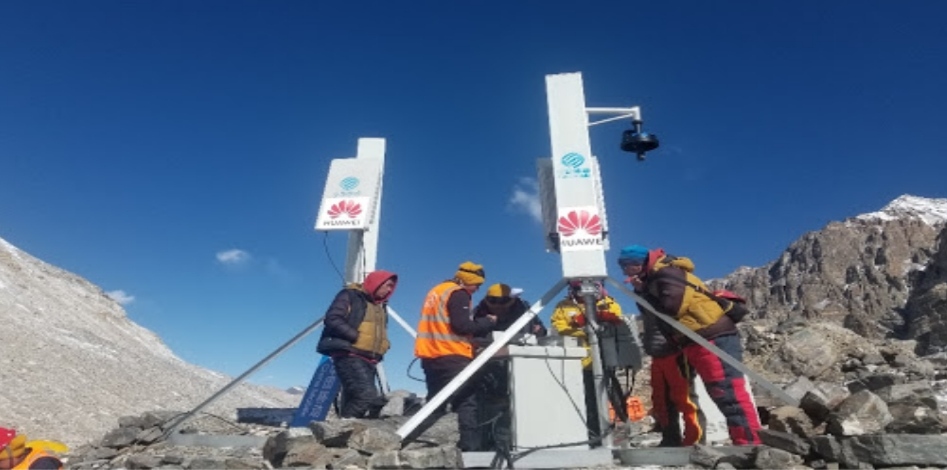

The recent installation of five 5G telecommunication base stations below Mt Everest, one of them at the height of 6,500m at advanced base camp on the north slope of Mt Everest, is an effort to boost communication between mountaineers and organise speedy relief efforts. It is seen as yet another evidence to suggest the vision of a ‘progressive Everest’ China has for its side of the mountain.

Workers putting up a 5G base station at a height of 6,500m above sea level on the north slope of Mt Everest.

The narrative on the southern Sagarmatha side of the mountain in Nepal is different. Ever since it was first climbed in 1953 by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay of the British John Hunt expedition four years after Nepal opened up to the western world, Everest has been synonymously associated with Nepal’s mountain tourism.

Climbing fees and expedition expenditure on Mt Everest of as much as $8 million a year have provided a big source of revenue earnings for Nepal. Climbing from the Nepal side was closed in 2014 after an avalanche killed 16 Nepali climbers on the Khumbu Icefall, and in 2015 after 18 people were killed in another avalanche at Base Camp after the earthquake.

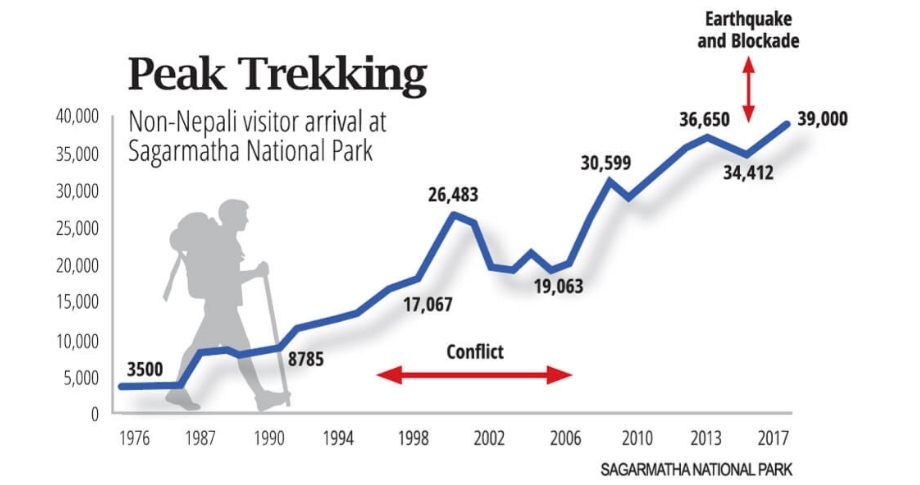

Figures from 2016 show that trekking in Everest rose by over 9,000 visitors, contributing to significant employment generation and economic recovery for the local community. Climbing fees are $11,000 per non-Nepali mountaineer for expeditions from the Nepal side, and $8,000 from the Chinese side. But scaling Mt Everest from Nepal has been attractive to climbers because of more reliable access to the mountain, laxer regulations on the number of climbers, alongside the cultural experience of living and breathing with the local people.

However, in recent years, Everest expeditions from the Nepal side also became famous for the wrong reasons. A photograph of the traffic jam on the summit ridge of Mt Everest taken by Nirmal Purja went viral in spring 2019, although other Nepali climbers argued that the media misrepresented and exaggerated what was going on in the mountain.

However, in recent years, Everest expeditions from the Nepal side also became famous for the wrong reasons. A photograph of the traffic jam on the summit ridge of Mt Everest taken by Nirmal Purja went viral in spring 2019, although other Nepali climbers argued that the media misrepresented and exaggerated what was going on in the mountain.

In 2019, Nepal issued 381 permits to climb Everest, out of which 11 mountaineers died– making it one of the deadliest climbing seasons. According to Alan Arnette, long-time Everest blogger, incompetent and inexperienced people in-charge of commercial expeditions were a major cause. Lack of regulation has made Mt Everest climbing from the Nepal side more crowded and risker than it should be.

There is no cap on the maximum number of permits to climb Mt Everest, and the narrow weather window in late May led to dangerous overcrowding in some seasons. After worldwide criticism, Nepal issued a new regulation last year requiring Everest climbers to have previously climbed at least one peak inside Nepal over 6,500m, and guide companies to have at least three years of experience in organizing high-altitude treks.

The efficacy of this new rule could not be tested this year because all spring expeditions on Everest and all other mountains were canceled in March due to the coronavirus pandemic. However, China has taken advantage of the closure to have its own sole expedition from the north side to re-measure the exact altitude of Mt Everest using its own GPS satellite.

China has also completed an asphalt highway leading right into the North Base Camp on the Rungbuk Glacier in Tibet at 5,150m, giving expeditions from the north side an edge in terms of accessibility. Expeditions from the Nepal side have to fly to Lukla, and conduct a 10-day acclimatisation trek from the south side.

The Chinese have removed the remains of all dead climbers they could find from the north mountain, have fixed ropes all the way to the summit, and have also managed the garbage. Now, the installation of 5G technology adds to the growing evidence of China’s interest to improve connectivity in order to promote mountaineering and tourism on the north side of the mountain.

Ren Zhengfei, the founder of Huawei, when asked about why install 5G in a place with very few people, replied: “… But there may be an Internet that can save the climbers life.”

In the early 2000s, the difficulty in acquiring Chinese climbing permits was a factor that shifted the climbing business to Nepal. With its better infrastructure, and if permits are more forthcoming, it is only a question of time before more expeditions migrate to the north.

The lesson for the Nepal government is to step up its promotion efforts, and address issues like overcrowding, commercialisation, safety, and a more nuanced permit system. The advantage for the Nepal side is that the approaches to the mountain are within Sagarmatha National Park with no road access, much more varied topography, rich biodiversity, and cultural assets.

Nepal has a niche market for trekking and mountaineering which have not been fully exploited. There are alternative tourist attractions such as promoting astro-tourism for stargazers drawn to the night sky.

The Khumbu is not just the Everest trail, there are less travelled valleys like Thame, the Kongma, Cho La, Renjo three-passes trek, Gokyo, and even traverses like the Tasi Lapcha pass from Rolwaling which have now become less treacherous because of climate change.

These new routes would diversify the destination, provide a much-needed scenic and culturally-rich alternatives to the well-trodden Base Camp Trek, and encourage repeat visitors.

Increased competition from China and the looming threat of climate change in the Nepal Himalaya are a given. The question is how Nepal can promote its unique selling points and ensure that the local economy benefits more from mountain tourism. The COVID-19 lockdown is a perfect time to let the mountains heal, give time for the trails to rest, and identify Nepal’s niche so we can return to a better normal.