‘New Secret No. 5656’: The document that lifts the lid on life inside a Chinese re-education camp

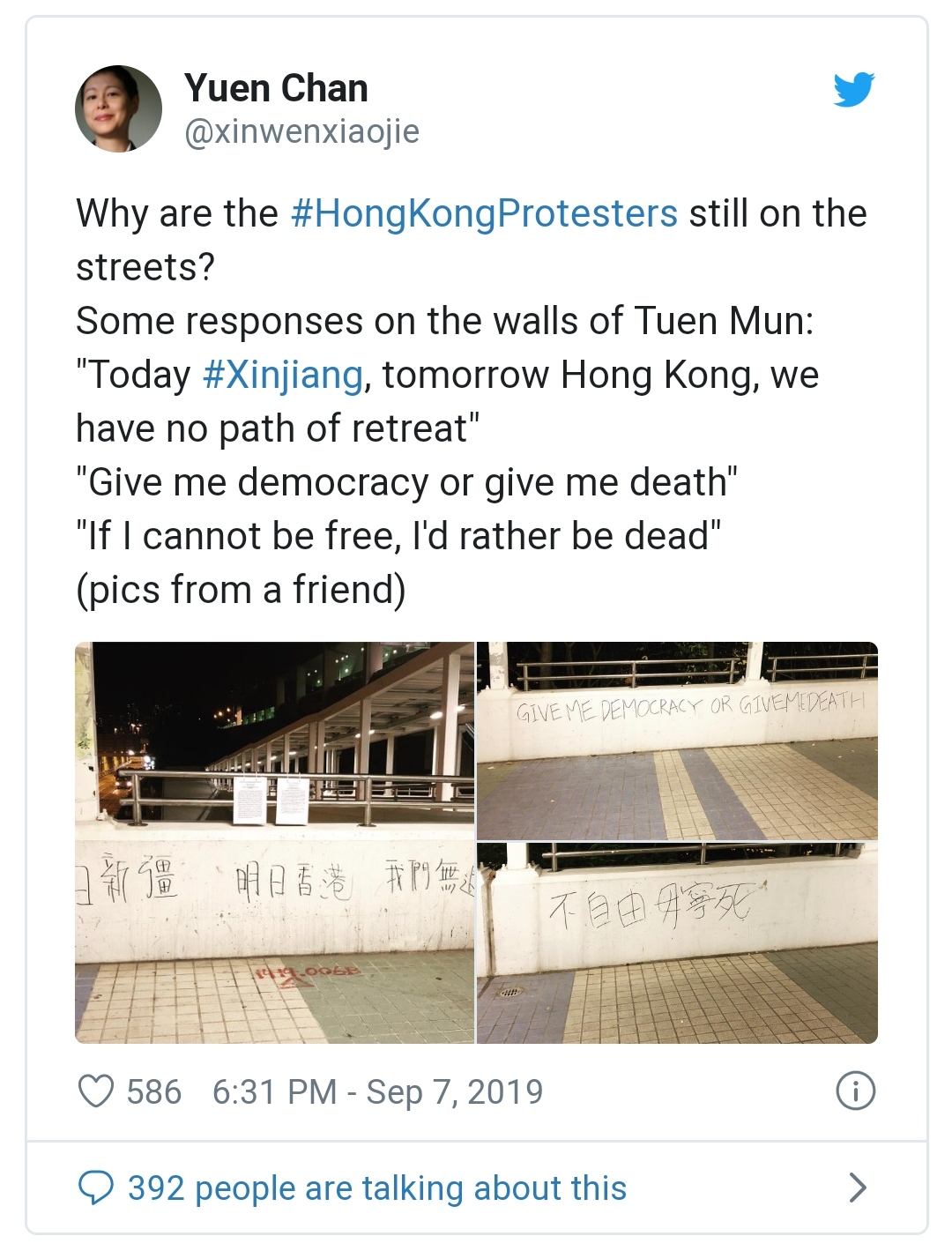

On a pedestrian overpass in Hong Kong’s battle-scarred township of Tuen Mun, a protester scrawled a slogan which speaks to the predicament facing the mutinous residents of the Chinese enclave.

“Today #Xinjiang, tomorrow Hong Kong, we have no path of retreat,” the characters read.

“Give me democracy or give me death,” it continues in English, using one of the slogans than sprang to prominence during the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations.

They know what’s coming because 3,000km to their north-west the very template for Hong Kong’s potential subjugation is being fine-tuned.

The autonomous region of far-flung Xinjiang is more easily hidden from prying eyes than the cosmopolitan special administrative zone of Hong Kong.

But recalcitrants like the Tuen Mun graffitist know that eventually there will be a reckoning — even if it takes another generation.

First it was Tibet, then Xinjiang’s turn. Hong Kong fears it is next.

Now, after two leaks in two weeks of confidential Chinese government documents, there’s a clearer view of what’s happening on the ground in Xinjiang.

A fortnight ago, the New York Times published 400 pages of internal party documents, including the text of a confidential speech made by China’s President Xi Jinping in 2014 exhorting authorities to unleash the “organs of dictatorship” on the region.

The documents equate the mindset of the people of Xinjiang to that of a “virus” as if were an infection in need of a cure.

And on Monday, ABC News in conjunction with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and 16 other international media partners, revealed another 23 pages of secret documents detailing Xinjiang’s descent into dystopia.

New Secret No. 5656

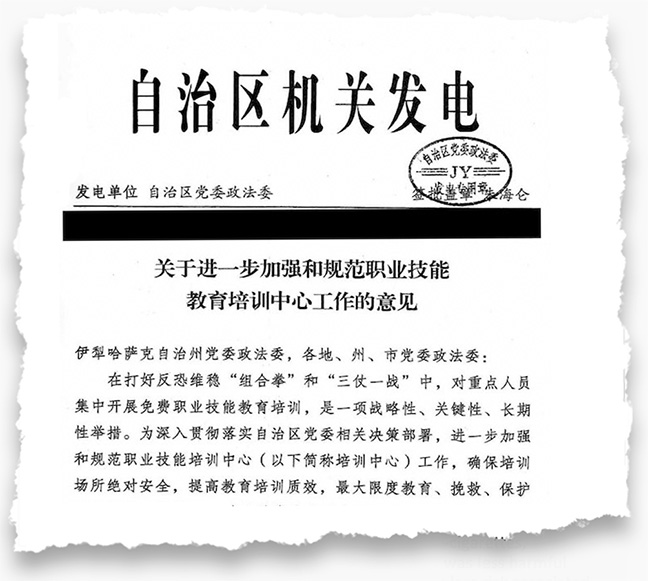

Among the most disturbing details are those found in the nine-page “telegram” that was one of the documents in the “China Cables” leak obtained by ABC News.

Issued by the Communist Party’s Xinjiang political and legal affairs commission, it was stamped: “New Secret No. 5656”.

The document dates from 2017, exactly the time when the mass arrests of Muslims from ethnic minority groups were taking place and scores of re-education camps began cropping up around the province as part of the government “anti-extremification” drive.

The campaign has seen more than a million members of Xinjiang’s Muslim minorities rounded up and put through the re-education system.

China has denied these claims and says that Muslims — mainly those from the 10-million-strong Uyghur community — are simply undergoing training and that the camps are vocational training centres where personal freedoms are guaranteed.

But Secret No. 5656 blows that cover to smithereens.

It’s a 25-point list of dos and don’ts — an instruction manual for how to run a camp where inmates’ lives are controlled to the nth degree.

Titled “Opinions on further strengthening and standardising vocational skills education and training centres”, the document goes into minute detail about security practices, using the language of high-security prisons.

While the memorandum speaks of “students,” it spells out the need to “prevent escapes” and that all doors must be “double-locked and must be locked immediately after being opened and closed”.

The Chinese phrase for “double-locked” is understood to refer to a system where there are two locks and a different person has the key to each lock.

With two people required to unlock a door, a would-be escapee needs to overpower two people. With two keyholders, each one vets the other.

In Xinjiang, even the gatekeepers can’t be trusted.

That’s what’s also known as the “two-man rule” or the “no lone zone” — the type of failsafe system used in places such as nuclear missile facilities.

And all this security for students in a vocational training centre.

The bricks and mortar of repression

Secret No. 5656 is also peppered with spatial instructions to ensure “perfect peripheral isolation”, to maintain “internal separation”, to avoid “blind spots” and to observe “protective defences”, as if every inmate was a suicide bomber in waiting.

But these instructions describe facilities for men and women whose only indiscretion may have been to fast before dawn, to wear a headdress or beard, to own a compass or tent or to refuse to hand over their phone to be scanned.

We know that because five years ago Chinese authorities In Xinjiang published a list of 75 “suspicious activities” which contained examples as benign as these.

Secret No. 5656 deals mainly with the bricks and mortar of repression. It is complemented by a digital component which has been described as the “central nervous system” of the surveillance state.

Those who trip the wire are red-flagged by this network, which collects and processes large amounts of data using machine learning and artificial intelligence.

James Mulvenon, who runs the intelligence program for a leading US defence contractor, says this model of policing predicts where laws might be broken as well as identifying those who might break them.

“And then they are pre-emptively going after those people using that data before they’ve even had a chance to actually commit the crime.”

Meaning that among those in the camps, there are some whose only crime is to have been flagged by an algorithm as someone who might be about to break the law.

Samantha Hoffman, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, describes this as “the language of state terror”.

“Part of the fear that this instils is that you don’t know when you’re not ok. One day you’re fine and the next day you’re not,” she says.

“If you don’t know that you’re on a blacklist of some sort, that can be even more powerful than if you do. That’s how state terror works.”

Changing hearts and minds

Which is why Secret No. 5656 is also a manual on how to forcibly bring about cultural and habitual change.

In part, it reflects the long-held view from Beijing that Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang need the civilising influence of Chinese customs and culture.

But it also projects the broader aim of “behaviour management” designed to hardwire people to accept “civility and courtesy, compliance and obedience, and unity and friendship behaviours and habits”.

For the people of Hong Kong, there’s a familiar ring to the rhetoric and warnings now coming from Beijing.

After protesters tossed petrol bombs at police stations in August, Chinese officials described the escalating violence as showing “signs of terrorism”.

In October, the People’s Daily described Hong Kong’s education system as a “disease”, blaming compulsory liberal studies classes where students are taught critical thinking for the “poisoning it has brought on to the youth’s minds”.

Terrorism, viruses, disease, poison. Hong Kong and Xinjiang are at opposite ends of greater China with vastly different cultures and beliefs, but in Beijing’s eyes, the threat is one and the same.

For the people of Hong Kong, the Xinjiang document leak is not some faraway abstraction that is someone else’s concern. It’s a glimpse into what could happen in their own, near future.