Parts of India becoming Quite hot for humans

A signatory to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, India has pledged to cuts its carbon emissions by 2030 by 35% below 2005 levels.

Last month, the Government announced plans to add 500 gigawatts of renewable energy to the country’s power grid by 2030. By that year, renewable energy should account for at least 40% of India’s installed power capacity. The country is also planting forests to help mop up carbon emissions.

Climate Action Tracker, a site that analyzes countries’ progress, says India is making good headway but could do more by reducing its reliance on coal power stations.

A report by India’s Central Electricity Authority released this week found that coal power could still account for half of India’s power generation in 2030, despite the country’s investments in solar.

It will be better for the CLIMATE ACTION TRACKER to get after the USA and the Europeans who have ravaged the planet for last few 300 years to admit India in the Nuclear Supplier Group forthwith. Then India can accelerate its plan to generate more power through nuclear reactors. Otherwise India will keep using Coal without doubt.

The NSG group should know that Indian nuclear weapon programme will keep advancing by leap and bounds irrespective of the fact that it becomes a member of the NSG or not. The MTCR imposed on India earlier could do nothing to stop India from becoming a missile power.

Coming back to climatic changes, heat waves in India usually take place between March and July and abate once the monsoon rains arrive. But in recent years these hot spells have become more intense, more frequent and longer. However such happenings are not cofined to India alone. Both USA and Europe are worst sufferers in this regard and unlike Indians they are not used to such heat.

The Western Researchers think that India is among the countries expected to get affected by the impacts of climate crisis, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) say that even if the world succeeds in cutting carbon emissions, limiting the predicted rise in average global temperatures, parts of India will become so hot they will test the limits of human survivability.

“The future of heat waves is looking worse even with significant mitigation of climate change, and much worse without mitigation,” said Elfatih Eltahir, a professor of hydrology and climate at MIT.

In case MIT is so worried about Indians, it should first ask USA to reduce its Carbon emissions 50 % without further delay. Then it should help India to obtain most of its power from renewable sources. Otherwise they need not worry, we Indians know how to take care of ourselves.

Last year, there were 484 official heat waves across India, up from 21 in 2010. During that period, more than 5,000 people died. This year’s figures show little respite.

In June, Delhi hit temperatures of 48 degrees Celsius, the highest ever recorded in that month. Churu in Rajasthan nearly broke the country’s heat record with a high of 50.6 Celsius. Bihar, closed all schools, colleges and coaching centers for five days after severe heat killed more than 100 people.

The closures were accompanied by warnings to stay indoors during the hottest part of the day, an unrealistic order for millions of people who needed to work outdoors to earn money. And forecasters believe it’s only going to get worse.

“In a nutshell, future heatwaves are likely to engulf in the whole of India,” said AK Sahai and Sushmita Joseph, of the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, in Pune in an email.

India’s situation is certainly not unique. Many places around the world have endured heat waves so far this year, including parts of Spain, China, Nepal and Zimbabwe.

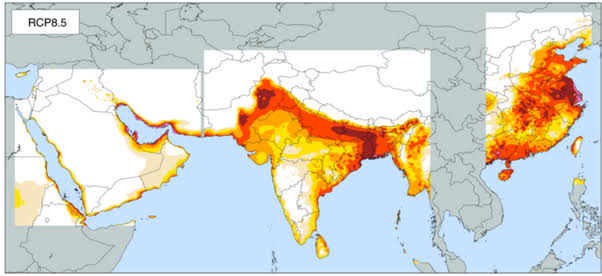

To examine the question of future survivability of heat waves in South Asia, MIT researchers looked at two scenarios presented by the IPCC: The first is that global average surface temperatures will rise by 4.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

The second is the more optimistic prediction of an average increase of 2.25 degrees Celsius. Both exceed the Paris Agreement target to keep the global average temperature rise by 2100 to below 2 degrees Celsius.

Under the more optimistic prediction, researchers found that no parts of South Asia would exceed the limits of survivability by the year 2100.

However, it was a different story under the hotter scenario, which assumes global emissions continue on their current path.

In that case, researchers found that the limits of survivability would be exceeded in a few locations in India’s Chota Nagpur Plateau, in the northeast of the country, and Bangladesh.

And they would come close to being exceeded in most of South Asia, including the fertile Ganges River valley, India’s northeast and eastern coast, northern Sri Lanka, and the Indus Valley. of Pakistan. Survivability was based on what is called “wet bulb temperature” — a combined metric of humidity and the outside temperature.

When the wet bulb reaches 35°C it becomes impossible for humans to cool their bodies through sweating, hence it indicates the survival temperature for humans. A few hours of exposure to these wet bulb conditions leads to death, even for the fittest of humans.

Though these research are highly motivated and can be easily challenged, India is already developing a robust nationwide Heat Action Plan.

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) is working with state health departments to create an early warning system that would notify millions of people by text message about ways to stay cool, when heat waves hit.

power. Given the more frequent heat waves and dire future predictions, capping a rise in global temperatures could very well turn out to be not India’s but Europe’s and America’s most important challenge in decades ahead.