Secret Massacre of Indigenous Tasmanians By The Britishers almost 200 years Ago

By

Rachel Edwards

Dated : 29 Dec 2020 (IST)

McNally’s diary is the only account by an “ordinary soldier” of life in the penal colonies, says Professor Sharpe.

A soldier’s diary disintegrating in Ireland’s national library has revealed disturbing evidence of an undocumented massacre of Aboriginal people in Tasmania in the colony’s early years.

The diary belonged to Private Robert McNally, posted to Van Diemen’s Land in the 1820s, and records in gritty detail colonial life and encounters with settlers and a notorious bushranger.

But it’s his account of his part in the cover up a massacre of men and women on March 21, 1827, near Campbell Town in the Northern Midlands, that stunned University of Tasmania history professor Pam Sharpe.

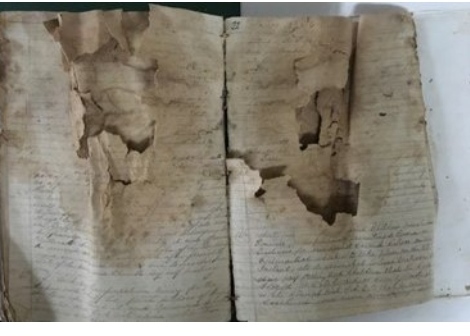

Searching the National Library of Ireland catalogue for documents about settlers, Professor Sharpe found a note referring to “two volumes in bad condition” of a soldier’s writings.

The National Library of Ireland is restoring Robert McNally’s diaries.

Unearthed, the diaries were identified as the work of McNally, an Irishman who served in Ireland, India, Sydney and Van Diemen’s Land, Professor Sharpe told ABC Radio Hobart.

Professor Sharpe said she approached the find with low expectations, but that soon changed when she got her hands on the first of two notebooks.

“I didn’t hold out much hope that it would be interesting, but I opened it and it was absolutely fascinating,” she said.

What she read prompted Professor Sharpe to divert her research funding to have the handwritten entries digitised. Efforts are underway to conserve what remains of a second McNally volume in poor condition.

“It is extremely unusual, very valuable, and completely worth diverting my research to investigate because some of these things aren’t on the record about Van Diemen’s Land,” Professor Sharpe said.

Campbell Town today, near the scene of a chilling episode recorded by McNally.

She said the diaries recounted McNally’s time with the infantry from 1815 to 1836.

“He gets to Van Diemen’s Land around about the time that Governor [George] Arthur comes — 1825. He’s here for three years,” Professor Sharpe said.

“The critical thing is that it’s the only diary of an ordinary soldier that anyone has found for colonial Australia.”

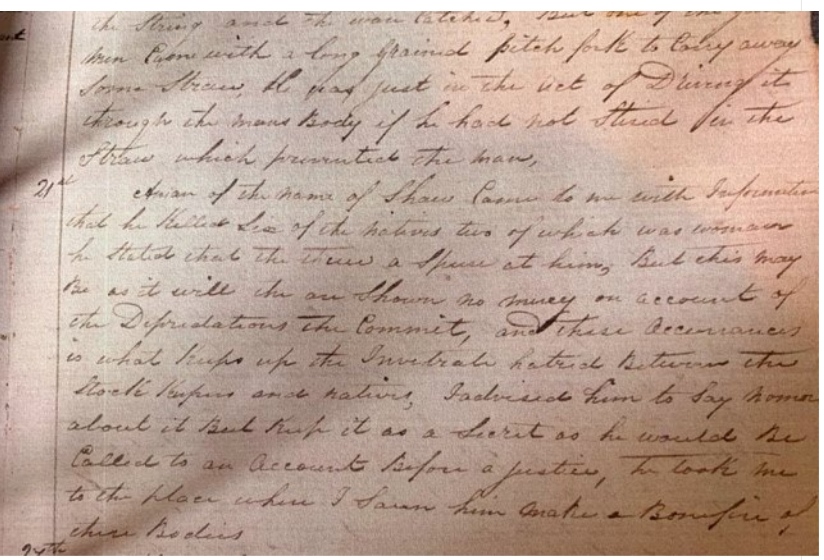

Professor Sharpe said she was disturbed to read McNally’s account of the aftermath of a deadly confrontation between a livestock handler named Shaw and local Indigenous people on the Sutherland Estate.

“McNally doesn’t actually see any Aboriginal people for the first few months, but then he is involved in some alarming episodes,” she said.

“He was called to [the scene of] a massacre that my researchers and I can’t find any other evidence of.”

McNally wrote:

“A man of the name of Shaw came to me with information that he had killed six of the natives, two of which was woman.

“I advised him to say no more about it but keep it as a secret as he would be called to an account before a justice. He took me to the place where I saw him make a bonfire of these bodies.”

Robert McNally has written about witnessing a horrific massacre of Aboriginal people.

A lot of violence perpetrated against Aboriginal people happened in remote areas of Van Diemen’s Land and many incidents were not recorded, Professor Sharpe said.

“It is horrific, absolutely awful, but unfortunately it is probably the story of what happened to a lot of Aboriginal people in the 1820s,” she said

The University of Newcastle’s Professor Lyndall Ryan, who created an online map of massacres in Australia, said there were lots of massacres that never came to light.

“Most of them were carried out in secret. If you were caught, you would be hanged,” Professor Ryan said.

Heather Sculthorpe, chief executive of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, said any new information would need to be substantiated.

“It will be exciting if there is new information, but we do need it to be historically verified,” she said.

“There has been a lot of work done on the history of Tasmania, but of course there is more to be found.

“The way that colonials would have written about massacres would have been hidden.”

Professor Sharpe said she had only had four hours to examine the McNally diary before returning home to Hobart. She hadn’t even seen the second volume, because it was covered in mould and deemed too fragile.

But the research continues.

“After a lot of effort, and the involvement of the Irish ambassador to Australia, the National Library of Ireland is now conserving [the second volume],” Professor Sharpe said.

“It is undergoing an enormous restoration process in the Marsh’s Library in Dublin, where they’re experts on 18th century paper conservation.”

Private Robert McNally recounts coming eye to eye with Matthew Brady, centre, who was known as the gentleman convict.

According to his diary, McNally witnessed another famous event in Tasmania’s history.

Matthew Brady was known as the “gentleman bushranger” and one of his most audacious actions was the capture of the entire township of Sorell, near Hobart, in November 1825.

His “gentlemanly”attributes included rarely robbing women and fine manners while stealing from men.

Professor Pam Sharpe says she was surprised to find the level of detail in the diaries.

“To start with [McNally is] chasing Matthew Brady, who more or less held the whole island to ransom,” Professor Sharpe said.

“I mean, Brady and his gang are running rampant.

“Robert is part of the military force trying to capture him and they have an eyeball-to-eyeball encounter at Sorell jail and Brady gets away yet again.

“That’s quite a famous episode, so it’s just fantastic to have a very close and detailed account of this.”

Professor Sharpe said the McNally diary also documented the minutiae of colonial life.

“There is a lot of everyday detail, including what they wore, what they do all the time and all the drinking they do, which is immense,” she said.

“He recounts his liaisons with women. We have a lot of quite explicit detail of his affairs, which I hadn’t expected of an early 19th century journal.

“He really struggles with forming relationships with women.”

Professor Sharpe said McNally was born in the 1790s and died in 1874 in Ireland.

She said she had strong indications the diary was McNally’s own work and not that of an amanuensis, or person employed to take dictation or copy other people’s experiences, which was common at the time.

She said the library conservator had established the diary was very early 19th century handmade paper.

International effort underway to restore a piece of Tasmanian history

“We’ve been able to fact check against military records, newspaper reports and so far, Robert McNally is where he says he is,” Professor Sharpe said.

“We know that writers of military memoirs sometimes put themselves into the spotlight, as Albert Facey did in A Fortunate Life when he gives a description of the beginning of Gallipoli, when we know he wasn’t there.

“In the McNally diaries there is quite a famous incident in Ireland called the Churchtown Burnings and Robert says he is nearby but not actually there.

“This gives us confidence that, when he gives himself a central role in the Sorell jail hold-up by Matthew Brady a few years later, he was actually there, and he did what he describes.”

Robert Hogan is working as a research assistant on the diaries, and has found Private McNally’s service record in the British National Archives.

“The information he gives in the journal is consistent with military history,” Mr Hogan said.

“I found that he joined the 96th Regiment in 1816 and when they disbanded in 1818 he moved immediately to join the 40th Regiment.

“His length of service in each place is consistent with what he says in his diaries.”