Serious Issue (The planet’s plastic problem) : Why we need a global plastics treaty?

A global plastics treaty is urgently required to limit plastic’s contribution to climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. But this will not be easy to arrive at.

Black-bellied Whistling-Ducks stand on a log as plastic bottles and trash float on the the El Cerron Grande reservoir in Potonico, El Salvador September 8, 2022. REUTERS/Jose Cabezas

Plastic waste is everywhere, from the peak of Mount Everest to the floor of the Pacific Ocean, inside the bodies of animals and birds, and in human blood and breast milk.

On Tuesday (April 23), thousands of negotiators and observers from 175 countries arrived in Ottawa, Canada, to begin talks regarding the very first global treaty to curb plastics pollution. Scheduled to run till April 29, this is the fourth round of negotiations since 2022, when the UN Environmental Assembly agreed to develop a legally binding treaty on plastics pollution by the end of 2024. The final round will take place in November this year, in South Korea.

Experts believe that the proposed treaty will be the most important environmental accord since the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, in which nations agreed to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Here is what you need to know.

Why is a global plastics treaty needed?

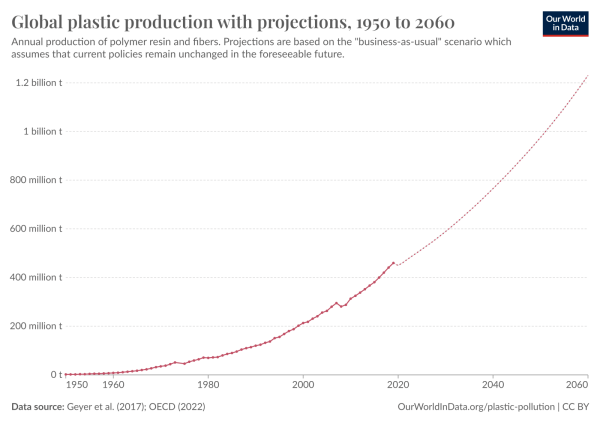

Since the 1950s, plastic production across the world has skyrocketed. It increased from just 2 million tonnes in 1950 to more than 450 million tonnes in 2019. If left unchecked, the production is slated to double by 2050, and triple by 2060.

Even just in the last two decades, global plastic production has doubled. (Credit: Our World in Data)

Even just in the last two decades, global plastic production has doubled. (Credit: Our World in Data)

Although plastic is a cheap and versatile material, with a wide variety of applications, its widespread use has led to a crisis. As plastic takes anywhere from 20 to 500 years to decompose, and less than 10% has been recycled till now, nearly 6 billion tonnes now pollute the planet, according to a 2023 study published by The Lancet. About 400 million tonnes of plastic waste is generated annually, a figure expected to jump by 62% between 2024 and 2050.

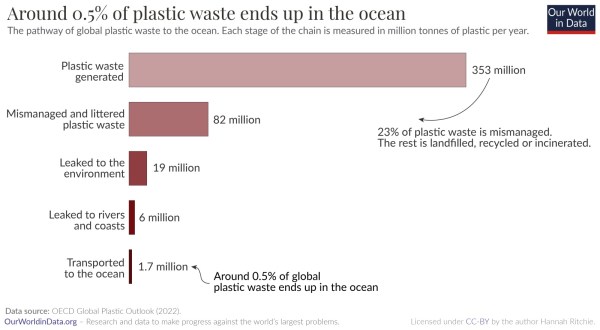

Much of this plastic waste leaks into the environment, especially into rivers and oceans, where it breaks down into smaller particles (microplastic or nanoplastic). These contain more than 16,000 chemicals which can harm ecosystems and living organisms, including humans — the chemicals are known to disturb the body’s hormone systems, cause cancer, diabetes, reproductive disorders, etc.

As shown in the chart, much of the plastic waste is leaked to the environment; a further fraction makes its way to the ocean. (Credit: Our World in Data)

As shown in the chart, much of the plastic waste is leaked to the environment; a further fraction makes its way to the ocean. (Credit: Our World in Data)

Plastic production and disposal are also contributing to climate change. According to a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in 2019, plastics generated 1.8 billion tonnes of GHG emissions — 3.4% of global emissions. Roughly 90% of these emissions come from plastic production, which uses fossil fuels as raw material. If current trends continue, emissions from the production could grow 20% by 2050, a recent report from the United States’ Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory said.

What can the treaty entail?

While none of the treaty’s details have currently been finalised, experts believe that it can go beyond just putting a cap on plastic production in UN member states.

The treaty can theoretically lay out guidelines on how rich nations should help poorer ones meet their plastic reduction target.

It may also ban “particular types of plastic, plastic products, and chemical additives used in plastics, and set legally binding targets for recycling and recycled content used in consumer goods,” according to a report by the Grist magazine.

The treaty can mandate the testing of certain chemicals in plastics.

It can also have some details on just transition for waste pickers and workers in developing countries who depend on the plastic industry for a living.

What are the roadblocks to the treaty?

Such an ambitious agreement, however, is far from guaranteed. Some of the biggest oil and gas-producing countries, as well as fossil fuel and chemical industry groups are trying to narrow the scope of the treaty to focus just on plastic waste and recycling.

Treaty negotiations, so far, have been deeply polarising. Since the first round of talks in Uruguay in November 2022, oil-producing nations like Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Iran have opposed plastic production caps, and are using myriad delay tactics (like arguing over procedural matters) to derail constructive dialogues.

For instance, countries are yet to decide if the plastics treaty would be agreed upon by consensus or through a majority vote, according to a report published in the journal Nature. Consensus would mean that a single country could veto the treaty, and prevent it from getting passed.

On the other end, there is a coalition of around 65 nations — known as the “High-Ambition Coalition” — which seeks to tackle plastic production. The coalition, which includes African nations and most of the European Union, also wants to end plastic pollution by 2040, phase out “problematic” single-use plastics, and ban certain chemical additives that could carry health risks.

The US has not joined the HAC. While it has said it wants to end plastic pollution by 2040, unlike the HAC, it advocates that countries should take voluntary steps to end plastic pollution. “The underlying reason why the US is not ambitious is we are a fossil gas country,” US Senator Jeff Merkley (Democrat from Oregon) told the Associated Press.

Fossil fuel and chemical corporations are also working to water down the treaty, and have sent a record number of lobbyists to the negotiations in Ottawa. According to a recent analysis by the Centre for International Environmental Law (CIEL), 196 such lobbyists registered for the talks, a 37% increase from the 143 lobbyists registered in the previous round of the negotiations in Kenya last November.

“99% of plastics are derived from fossil fuels, and the fossil fuel industry continues to clutch plastics and petrochemicals as a lifeline. The chemical and fossil fuel industries oppose cuts to plastic production, falsely claiming that the plastics crisis is not a plastic problem, but a waste problem,” the analysis said.

It is due to such roadblocks that the previous three rounds of negotiations have failed to make significant progress regarding the treaty.