Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean in Antiquity

By

Prof Sudharshan Seneviratne

Sri Lanka will be the designated Chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) from 2023 to 2025. The 23rd meeting of the IORA Council of Ministers is held today The Committee of Senior Officials were held from 9-10 October 2023.

A land known by many a name to the World Systems located to the East and West of this island, its history is essentially a story of trans-oceanic connectivity. It is a story of how this island came to evolve its unique personality due to the convergence of multiple streams of people, cultures, languages, religions, ethnicities and technologies. It also represents a vibrant dynamic of authentic multiple histories of the Sri Lankan mosaic. The historical saga of Sri Lanka, an island situated in a pivotal position in the Indian Ocean Rim, could not be inscribed otherwise in the annals of history and most certainly not without the story of the sea – a story of nurtured reciprocity as one of the most valued ‘ports of call’ in antiquity.

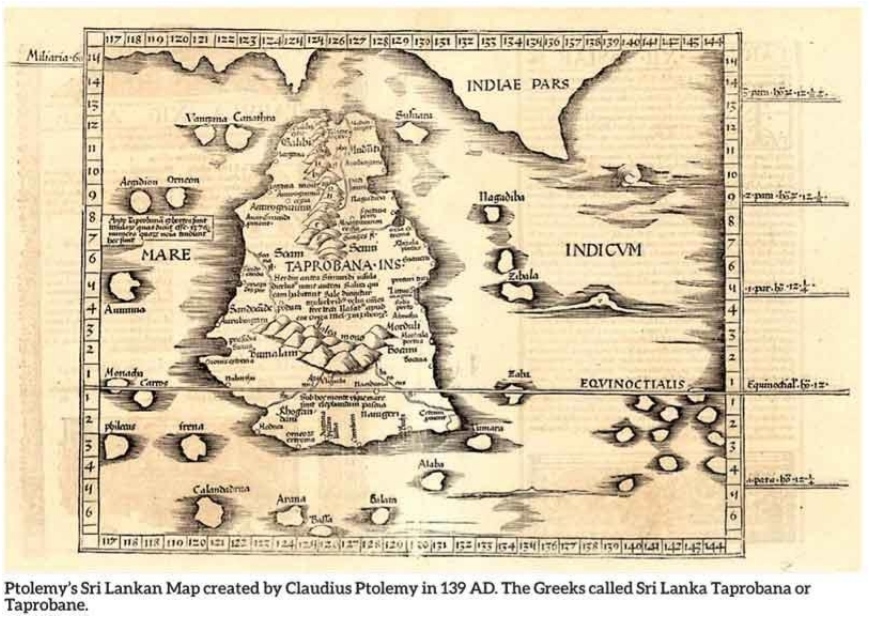

The island of Sri Lanka is also known in history by different names, including Tambapanni, Lanka, Taprobane, Serendib, Ceilo, Ceylon and eventually Sri Lanka or the ‘Resplendent Island”. Legends and historical annals note peopling of Sri Lanka associated with the ocean or those who traversed the ocean arriving at the shores of this island.

It was the Indian Ocean that nurtured the personality of Sri Lanka and shaped its landscape and cultural scape since pre-historic times. It is also the Indian Ocean, which binds us to the larger oceanic scape and the communities of the Indian Ocean rim with a common thread. The ocean is also the greatest repository that gifted the line of communication and resources. The cultural timeline of our connectivity with the

Indian Ocean goes back to pre-4000 BCE. The earliest common term known for this ocean is Samudra, as recited in the Rig Vedic hymns (C.1500 BCE). It is also known to have a Western and Eastern ocean.

The earliest texts mention oceanic seafaring luxury trade (‘From every side, O Soma, for our profit, pour thou forth four seas filled with a thousand-fold riches.” RV 9.33.6). The ocean craft in Sanskrit Vedic literature is known as Nau (neva in Sinhala).

Seafaring provided connectivity to multiple kingdoms, cultures and civilizations that thrived over time and space during the pre-modern period of the Indian Ocean Rim. Sri Lanka was a prime recipient of this Indian oceanic connectivity. Our relationship with the ocean is an interdependent factor which is mainly due to the centrality of our location in the Indian Ocean and the commonality shared by its resident communities.

Antiquity of Connectivity

Legends, chronicles and material evidence place Sri Lanka as a recipient culture located in the centre of the Indian Ocean.

The antiquity of this convergence dates to the pre-historic period when people, floral and faunal evidence indicate migration to Sri Lanka from the Indian sub-continent, South East Asia and East Africa. Pre-historic Austronesian engagement connected East Africa via South Asia and beyond. Legend has it that the pre-historic community, the Naga, were a seafaring community associated with trade and gems.

In the world of antiquity, Sri Lanka possessed a nautical history involving ships, navigation and seafaring by its island community dating to C. 1000 BCE. By the 4th Century BCE, even before the discovery of the monsoon by Hippalus, Sri Lanka was connected with South East Asia, East India and the Bay of Bengal, trading mainly on precious metals, elephants, spices and pearls.

The Bay of Bengal formed a sub-region in the Indian Ocean having its dynamic in the history of trade and commerce. By the early 4th Century BCE, this island was primarily a production-distribution portal within the Rim and reached even to the Mediterranean and the Far East.

The discovery of large quantities of Mediterranean, East African, South Asian and West Asian imported luxury ceramic ware and beads including coins and foreign notices (from the Mediterranean to the Far East) confirms the status of Sri Lanka as a major trading hub through long-distance trade linked to multiple lands.

Trading portals were located at convenient coastal sites suitable for safe anchorage (dating to the 10th Cent. BCE). In addition to events documented in the Mahavamsa and Jataka narratives, the most accurate and extensive travel catalogues perhaps are found in the cartographic evidence of Ptolemy’s Taprobane and the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a diary of a ship captain travelling between the Red Sea and India. Both mention Sri Lanka as an important travel destination for commerce, its emporiums and traded items including place names of the island.

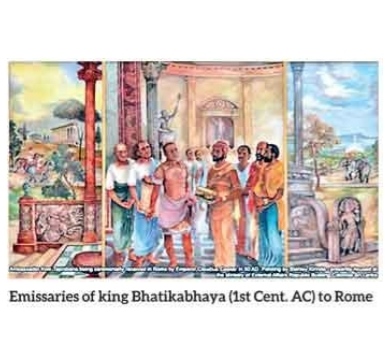

It is not a coincidence that during the same period (according to notices of Pliny) and the Mahavamsa emissaries of King Bhatikabhaya (1st Cent. AC), the first diplomatic mission (headed by traders), arrived in Rome during the reign of Emperor Claudius Caesar.

A second delegation from Sri Lanka arrived in Rome during the time of Emperor Julian (Circa A.D. 375). The latter period coincides with the reign of Mahasena, the age of great agrarian production, the construction of mega reservoirs and monasteries (Jetavana) and the intense expansion of foreign trade with the establishment of cosmopolitan Port Cities.

The commercial vortex connecting the Indian Ocean Rim had developed a complex system by the Middle Historic period (post 3rd Cent AC). This period witnessed intense commercial activities reaching out to India, South East, Far East and West Asia.

There are notices that Buddhist monks and nuns accompanied merchants to their travel destinations. Monasteries housing Sri Lankan monks were established during the 3rd Century AC in Nagarjunakonda (Andhra) and the Gupta period in north India.

The Mahavamsa also records the existence of residences housing foreign merchants. The discovery of a Nestorian cross at the citadel of Anuradhapura is a testimony to the presence of West Asian traders’ residence at Anuradhapura.

Connectivity and outreach were possible due to advanced nautical technology dating to the pre-Christian period. It was a qualitative development beyond the outrigger canoe or teppam.

The advanced development of this vessel is depicted on coins and inscriptions as single-mast and double-mast vessels that traversed the Bay of Bengal and South Asia. Interestingly enough, it was also the famous spice and gem trail that

Connectivity and outreach were possible due to advanced nautical technology dating to the pre-Christian period. It was a qualitative development beyond the outrigger canoe or teppam.

The advanced development of this vessel is depicted on coins and inscriptions as single-mast and double-mast vessels that traversed the Bay of Bengal and South Asia.

Interestingly enough, it was also the famous spice and gem trail that connected Sri Lanka with the Arab traders of West Asia. Merchants, from this period and region, made their way to Sri Lanka through three trade routes: the Indian to the North, the traders to the East, and the Arab to the West. It is from this vantage point that we need to understand the movement of communities to Sri Lanka, especially from West Asia in the Middle Historic period.

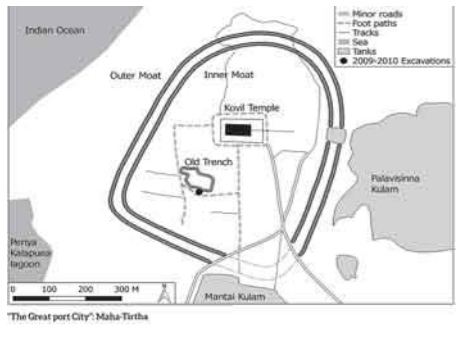

The very centrality of Sri Lanka was endowed with the location of large portals of cosmopolitan port cities. Godavaya (southeast Sri Lanka) and Maha-Tirta (northwest Sri Lanka) are classic examples. Mahatirta boasts of double moats covering 50 ha., with occupational levels dating from C. 3rd Century BCE to the 13th Cent AD. Excavations during several seasons yielded rice, pepper, cloves and everyday cereal foods, industrial remains, West Asian, Roman and Far Eastern ceramics, a range of coins and imported beads. It was the primary entrepot and the main hub of connectivity to the West and the East.

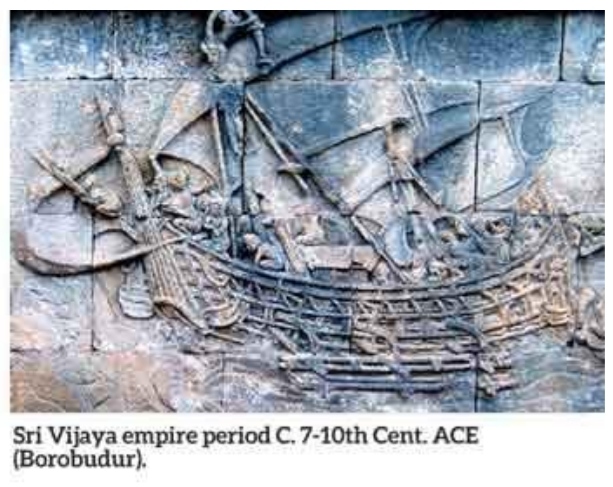

During the period after the 9th Century AD, an intense connection with South India and South East Asia developed. The oceanic enterprise was largely inspired by the Cola Empire (South India) and the Sri Vijaya Empire (South East Asia).

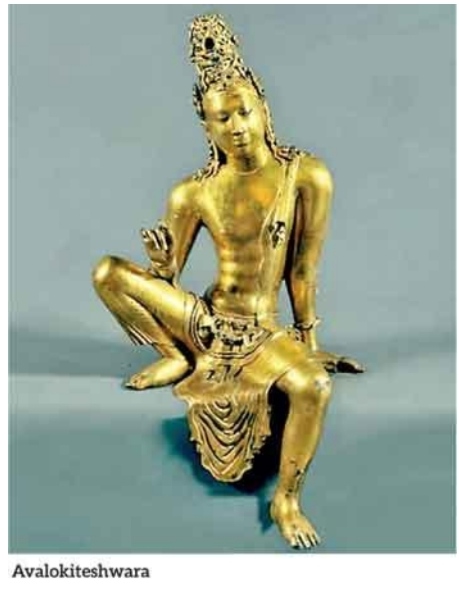

Similarly, particular Buddhist icons such as Avalokiteshwara and Tara extending from Nepal via Bengal through India and Sri Lanka to South East Asia were a movement associated with trade.

During this period nautical technology was at its zenith. The armada assembled in Eastern Sri Lanka by King Parakramabahu for his invasions of South India and ancient Burma coincides with this development.

The presence of West Asian merchants attracted by the spices and gems, is noted by Ibn Battuta (1330) and was seemingly located at port cities in Western and South Sri Lanka such as Chilaw.

Sri Lanka owing to its central strategic location within the Indian Ocean Rim, was a land of convergence for over thirty thousand years. Through these years Sri Lanka evolved into an island society representing a vivid ethno-cultural mosaic to complement the natural beauty of its landscapes and its incredible bio-diversity.

Thus, it presents a cross-culturally pollinated land of convergence within the Ocean Rim. Its cultural mosaic is blended with assimilative external and indigenous elements of commonalities and diversity.

The ocean history is synonymous with the history of this island. The arrival of colonial powers in the 15th Century to the Indian Ocean was a natural attraction to this richly endowed region of great wealth.

Source : Daily Mirror