Taiwan and lessons that can be learned from the Ukraine conflict

By

Robert Dujarric

U.S. President Joe Biden’s recent surprise visit to Ukraine has placed added pressure on Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to follow in the footsteps of the other Group of Seven leaders. Antagonism between China and the United States is rising — the latest episode focusing on alleged spy balloons — while Washington has been increasingly open in its backing for Taiwan.

So a year after the start of the Russian assault on Ukraine, we see war and tensions on both sides of Eurasia, with the possibility of a Chinese attack on Taiwan.

When Vladimir Putin tried to destroy Ukraine, most European Union states and the United Kingdom sided with Kyiv. Their combined economies are around 10 times larger than Russia’s and are technologically superior. They have more than 300 million more inhabitants than Russia. Russia’s national income is comparable to Italy’s, but its male life expectancy is at least 12 years shorter.

Yet, if the United States had not armed and funded Ukraine, the European response would have been inaudible. Europe welcomed millions of Ukrainian refugees and has given much economic and (some) military aid. But, Washington runs the coalition while supplying the bulk of the weapons and intelligence reaching Ukrainians. The Biden administration should have done a lot more but, without the United States, Ukraine would have faced Russia alone.

The reasons are simple. First, in exchange for the United States assuming a greater share of the burden, the allies accept U.S. leadership. Although imperfect, this deal has underpinned Western security and prosperity for more than 75 years.

Second, the EU has been an enormous success. But, in matters of war and peace, national governments unfortunately remain dominant, crippling unified European action.

Third, Europe’s largest power, Germany, is still partially paralyzed by its past. The cataclysmic end of Prussian-German primacy in Europe in 1945 regrettably makes German politicians and voters allergic to the logic of the philosopher of war, Carl von Clausewitz.

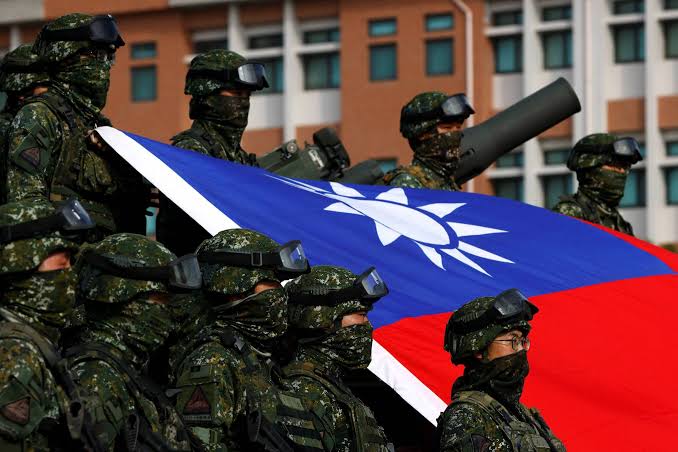

Turning to Asia, if China were to attempt to annex Taiwan, the island’s response is key. If Ukranians had not risen to the occasion, no amount of foreign weapons and money would have saved them. The same applies to Taiwan.

A second critical aspect will be Washington’s response. Will the U.S. just seek to back Taiwan indirectly or will it engage Chinese forces directly? No U.S. ally will do more than the Americans.

Much has been written about “Japan’s shift to war footing,” to quote a recent headline. But Japanese Cabinets still remain petrified about taking military action. Many foreign experts’ Japanese interlocutors come from a minority of (moderately) hawkish Japanese, giving foreigners the mistaken idea that Japan’s society is more martial than it really is. Japan, like Germany, wants to put behind it its brief, and by end of the war equally calamitous and criminal, adventure as a great power.

Chinese incursions into what Japan calls its territorial waters near the Senkaku Islands, which China calls Diaoyu, illustrates this point.

Other countries would have resorted to kinetic action to uphold their sovereignty, but Tokyo limits itself to lame statements (not necessarily wrong, but indicative of its mindset).

The Japanese evacuation of Afghanistan made it possible to airlift 15 Afghans (compared to 390 for South Korea and 15,000 for the United Kingdom).

Despite technology, no country can strengthen its armed services without putting more young men and women in uniform. In Japan the number of births fell by about half in four decades and there are few immigrants. How the country will find these new soldiers, sailors and airmen is a mystery. In the end, Japan will, at best, be a (possibly reluctant) follower of a U.S.-led coalition to defend Taiwan, especially if it involves fighting the People’s Liberation Army (and severing economic ties).

Another challenge will be forging a coalition. Due to the hub-and-spoke U.S. alliances and partnerships, relations between U.S. partners in Asia and Oceania are feeble, and, in the case of Tokyo and Seoul, marred by the so-called history issues arising from Japanese colonial rule. A lack of economic and political ties, and the tyranny of distance (Canberra is as far from Tokyo as Helsinki is) further keeps U.S. allies separate. “The Quad” and other security agreements between Japan and Australia do not alter this reality.

Moreover, the EU, despite its incomplete nature, can put in place sanctions, fund assistance and offers a constant forum for leaders, their ministers and officials to meet frequently. Nothing of the sort exists in Asia, further increasing the need for a U.S. initiative to lead the response to defend Taiwan.

The parameters will be different. The risks of the fighting spilling out of Ukraine into EU-NATO space have always been minor. In case Chinese President Xi Jinping attempts to annex Taiwan, the stakes of confronting Beijing will be much higher for Japan and other U.S. partners than facing Moscow is for Europeans.

This will make them more concerned about challenging China. At the same time, U.S. allies in Asia will see a Chinese invasion as a much greater threat to their core interests than most EU states west of Poland did when Putin attacked, pushing them into a more confrontational stance. No one can tell how governments will resolve these contrasting concerns.

The exact nature of a Sino-Taiwanese conflict is by definition unpredictable. But the events unfolding in Central Europe demonstrate that the response by Taiwan and of the United States will be a very important factor.