The Night Raiders : Good Morning Peshawar

Source : Bharat Rakshak

PART ONE

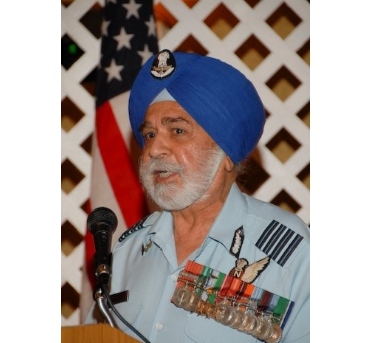

Gp Captain A S Ahluwalia

On September 13th, 50 years back the greatest bomber operation against Pakistan was launched by the Indian Air Force. It had all the drama and melodrama, climax and anti-climax, it was a yes, yes, no, no and then YES! It was the operation with the greatest precision on the part of the Indian Air Force, a top-secret mission, known to very few on the top–the AOC-in-C of the Western Air Command, the then CAS (now Marshal of the Indian Air Force) and a few staff officers working on the planning and execution of the mission.

These were the 4th and 5th Operational Missions for Gp Capt Amrik Singh Ahluwalia, who narrated the story in Chapter 16 of his book Airborne to Chairborne.

The article shares both his thoughts and the actual planning and execution of the mission and the top secrecy from India and a great surprise attack on Pakistan–never, ever, expected by them even in their dreams.

In all people there are two sets of feelings:

One is fear, the other is love.

If there is fear, then we shrink as a person.

But love, wow!

That can move mountains!

-Jorgen Roed (1808 to 1888), Danish painter

And for me it was love—love for my country, love for my air force, and love for flying, love for my people, love for my family and love for myself which just blew away even an iota of fear that may have tried to creep into my mind or my heart.

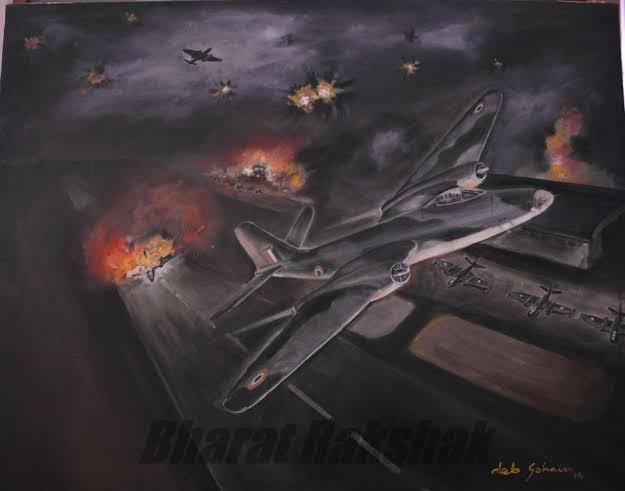

2200 hours, September 13 (was it the unfortunate and unlucky date for some?), 1965. Pitch dark and dismal night, with not a speck of light for miles. The moon was to come awake about two hours later. The “TOP SECRET” mission orders were in my brief case; the flight plan had been prepared for the sortie.

Sitting in the cozy but cramped cockpit of the Canberra bomber aircraft, with a small red shaded lamp throwing its circle of light on the map, I could only think of a long, momentous night full of melodrama, apprehension, and fear. I had something to think of—the duty ahead; others did not even know where they were headed to…………. yet.

My mind catapulted to and recapitulated the day’s events. One pilot and I, the bombardier-cum-navigator, had been called to the Operational Headquarters (Op HQ) in Delhi, for planning and leading an important assignment that night.

Afternoon……we were there and ushered into the Op planning hall; its walls covered with maps of different scales; colored pins were stuck all over, and ribbons crisscrossed. The huge, transparent, glass partition showed the fighter missions already in combat, or proceeding to, or returning from ground attack missions.

After a while, all concerned had assembled—the Chief of the Air Staff (CAS) [the first indication that the mission was positively important], the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) of the Op Command responsible for that sector of operations, the Command Intelligence Officer (CIO), the Wing Commander in charge of Bomber Operations (Bops), and the two of us.

Ahlu, we are approaching the Indus River bend,” came the soft and mellow voice of the pilot over the intercom. “I can see the reflection of the moonlight in the water,” he continued.

He had been flying the courses, speeds and height and turning according to the times, noted on his knee pad during briefing, and just mumbling those figures to me to ensure double check. I was sure that he was also, while flying, deep in his other thoughts.

I went into the glass covered nose, where I was going to be from now on until the bombing run was over. Craning my neck, I could see the clear reflection in the water and, as per our briefing, the pilot automatically started following the river. I rechecked the bombsight and its settings for my target.

“Tango-India to Victor Force….TIs directly overshot 500 yards from center, repeat, 5-0-0 yards overshoot. Out.” That was good considering that the TIs job is the most difficult because he has nothing to go by, and in the light of the flares, which he drops himself, he has to aim for the center point, before the flares go out, and drop the TI bombs.

“That’s the Kohat-Peshawar Road which we just crossed. Just did not see it coming up,” I told the pilot, who had also simultaneously observed what had happened, because of the interruption from Tango-India, and went into a tight turn to the right to follow that road northwards to our target and increasing to max speed simultaneously. I quickly adjusted the bombsight to offset for the error of the TIs.

“Coming to one minute to TOT, standby to pull up…..…….NOW.”

The crisp instructions from me, who was timing now, and the steep pull up to 4,000′ pushed me down in the prone seat with the force of gravity. Before we leveled out, I could see the TI bombs and started “homing” on to them through my bombsight.

As I commenced my bombing run commentary, my pilot had to remain quiet and only keep doing what was being instructed…. “4000 feet….Straight and level….left-left…left-left….steady, steady, steady…. right….right…steady… bomb doors open.”

[Between the crew, repeated practice, brings them to a level when the pitch, the quickness, the speed, and the loudness of the voice giving the directions, indicates the urgency and the requirement desired.]

I could feel the bomb doors opening from the shudder and judder due to the added amount of ‘drag’, and knowing that the pilot has the toughest time in maintaining his speed and direction at this stage, but he must, because it is the most crucial phase of the whole operation.

Knowing he would do his best, I continued my bombing run commentary: “Steady…..steady….steady…steady….steady, steady, steady, steady”.

I was now holding my breath as the TI bombs were coming into the cross (+) of the bomb sight and my ‘steady’ was becoming quicker like my heart beats.

As the cross and the TIs came together, I pressed the bomb release button and shouted, “Bombs gone…..bomb doors closed….climb to flight level 400 [40,000’], course 075.”

I was looking out to see the exploding bombs, which, as per the principle of bombing, would explode when the bombing aircraft is right over the target.

On seeing them explode where I had expected them to, I was happy that the attack had really gone home. As I was watching and giving instructions, the anti-aircraft from the ground opened up sending ‘tracers’ way past above us. We realized that the intelligence information was faulty and these guns could reach up to 7,000′.

To ensure safety of the aircraft and the mission, the pilot immediately broke RT silence: “Victor One to Victor Force, Victor One to Victor Force…bombing run height changed to 8,000′, repeat, 8,000’…all pull up to that height to avoid ack-ack. Out.”

It had taken more than four minutes for the anti-aircraft guns to get going in spite of the fact that Tango India had spent about that much time circling over target, dropping bright flares and then doing the run for the TI bombs, and then came us. It gave us great satisfaction that the surprise that we had planned for and were anticipating had been achieved.

Victor Force could now ‘home’ on to the anti-aircraft tracers to reach the target!! After about ten minutes, when we were nearing “Sierra,” the pilot again broke RT silence: “Victor One to Victor Force…Check. Over.”

“Victor 2, OK”. This was followed by all the others.

What a relief. All safe and well on their way back home! From “Sierra” we headed towards “Charlie”.

As we crossed the foothills and were entering the plains there was a frantic RT call: “Victor Leader this is Victor Seven…I am apparently being pursued by a Starfighter near Banihal…Appears to have fired a missile…taking evasive action…descending. Over.”

“Victor Seven this is Victor One…Roger…Try to keep down into the hills…and watch your fuel. He should not be able to stay long so far from home. Over!”

“Roger…Victor Seven”. After some tense seconds, came again: “Victor Seven to Victor Leader….I think he is gone. Did not have to go down much! Climbing back to height! Over”!

“Roger, Victor Seven. Keep check on fuel. Out”!

It appears that a lone Starfighter, taking a chance so far from home, was able to sight one of us, made a pass, but due to the mountainous terrain, could not succeed to lock on. Luck favors the brave.

Peacefully heading for base after a successful operation is a feeling which cannot be expressed in words. Your mind is overloaded with thoughts—thoughts of your dear ones back home; thoughts that you have not had rest for so long; thoughts of what all could have happened to you; thoughts of what must be happening on the ground to the people on whom you unloaded your bombs; thoughts of how much damage would have been caused; how many would have been killed; how many wounded; what chaos would have followed such a raid; thoughts why such wars; why cannot the whole world live in peace and forsake weapons; thoughts what would happen to our dear ones if similar raid was to take place over us; and so on and so forth the mind went. Then again the mind focused on the mornings happening to tie up with what actually happened over the target.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Having succeeded in ‘selling’ our plan, followed the arguments on the number of aircraft, the bomb loads, the airfields to standby for any emergencies, and many other aspects of an important mission, with emphasis on “Top Secret” being repeated by everyone around.

To the four suggested in the first plan, we suggested sixteen, which was shot down by the AOC-in-C outright, because it meant putting the whole squadron into the air against one target. We agreed, and reduced to twelve. Even that was not acceptable.

They came to eight. It was like bargaining; but what for? None of us probably knew.

Eventually, it was agreed that there will be eight bombers, one target indicator marker and one standby bomber up to “Charlie”.

We suggested each carries two 4,000-pounder bombs with fuses to detonate at 100′ above ground level. We were shot down. Reason—Overkill. It was a quick decision thereafter: four with eight 1,000-pounders each, and four with two 4,000-pounders each, and the standby with eight 1,000-pounders.

“Well, Gentlemen, it has been a good effort, well-planned, well projected, and we are confident that success should be on our side. I wish to re-emphasize that with all the planning we can go haywire, and it can be a catastrophe, if secrecy is in any way compromised.

No one, outside this room is aware of the target. Let it be so until you two,” pointing at me and the pilot, “are ready to actually launch from “Charlie”. Strict RT silence will be maintained until over target—come what may. Bops will inform and tie up with AOC “Charlie” for keeping the airfield on standby without lights from 2000 to 0400 hours tonight and keep a listening watch in the ATC at all times.

Other than being informed of the landing time of the Canberras at “Charlie” and about the radio silence, no other information need be given. He should have all his refueling bowsers filled up and ready on the tarmac. Bops will also inform “Alpha” to keep a dusk to dawn watch for any of our aircraft in emergency.

“Sierra” will not be available. “Able” should standby for the Canberras return in case need be. Good luck, may God Bless you all and Happy landings. Jai Hind!” That was the AOC-in-C’s concluding talk.

I was wondering in admiration, that we worry so much planning one operation; what about him who has to see all the operations through day and night throughout the war, of which we did not know where was the end yet, and accept both success and defeat as it comes, with bouquets and brickbats from the top—both service and civil.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The end of the thoughts of the morning briefing brought me out of my reverie as the pilot asked me how far we were from “Charlie”. Knowing that Pakistan radar must have been tracking us on our return to find out the base from which we had launched the attack on Peshawar, the possibility of a counter attack by PAF ground attack fighters on “Charlie” at “first light” could not be ruled out, so we had decided to immediately refuel and take off for home base as soon as possible.

Two hours and twenty five minutes after the launch from “Charlie” we landed back at that base—0245 hours September 14th, 1965. A quick refueling stop, a most refreshing mug of over-sweetened tea at the tarmac, kind courtesy the BC, and at 0330 hours we were off to our home base where we landed at 0430 hours, when most people, our own families, were snoring away, oblivious of the fact that there must be thousands of their kind already grieving in Peshawar.

It was 32 hours since I came home—the family was unaware where I was, because in those 32 hours I had been to Kanpur, Delhi, Agra, “Charlie”, Peshawar and back to “Charlie” and home. After a quick shower, while I was still moving, I realized that the wakefulness, the fatigue, and above all, the fear of the unknown—all take their toll in some form or the other…..Before I could eat even a few bites of my breakfast, I hit the pillow and was snoring.

Success also has its toll—the second Peshawar raid took place on September 16, 1965, a day after the first, and off I was again to Peshawar, but this time as Tango-India, with the CO of No. 5 Squadron, Wing Commander P.P. Singh.

These were the only two raids against Peshawar, and I had the privilege of being on both—once leading the bomber force, and the second time to mark the target for the bomber force to come.

It was said that a surprise raid at low level even by Canberras to Peshawar was impossible but then how can one forget the words by someone, I do not recollect, saying: “Only he who can see the invisible can do the impossible.”

“Hey! Ahlu. Do you see the runway?” The pilot on the intercom snapped me away from my thoughts. I strained my eyes in the blackness. Did we see the silhouette of a strip below?

“Turn around,” I called back.

Yes, it was “Charlie” airfield, shrouded in a dark mantle of a strictly enforced and extremely effective blackout. A low swoop over the air traffic control tower, three quick flashes of the wing-tip red and green lights, a waggle of the wings—the prearranged signal to total radio-telephony (RT) silence. Two specks of gooseneck flares killed the darkness around them, indicating the beginning and width of the runway. The authorities were expecting us as planned.

Stealthily, we came down in a shallow glide, crossing the threshold indicated by the two flickering flames, ease back gently on the joy-stick, cut throttle, softly touch mother-earth once again, as in thousands of landings before. We taxied behind the “Follow Me” jeep to the assembly area, switched off the two screaming Canberra jet engines and came out into the fresh, cool, clean, and pleasant air of the Punjab September night.

At one minute intervals followed eight more Canberras to embrace this land of the five rivers. Where is the standby tenth? Why was he still circling overhead? Come on…. land. After three unsuccessful endeavors the “Tenth” critically overshot the goose-neck flare markers, touched the runway nearly half-way down at a high speed; the end of the air strip was now rushing towards him; impossible to stop without overrunning the white concrete strip and also the over-run area at the far end.

One thousand yards to go; five hundred yards; four hundred; 3, 2……………. sit on the brakes, s-c-r-e-e-c-h. Watching, I prayed that “Tenth” does not block the runway.

“Ohh, no! What’s he up to?” I shouted to myself. The heavily laden aircraft, with eight 1000-pound bombs in her underbelly, was swinging to the right. The fire and crash crews had swung into action, rushing in the gloom towards the now inert aircraft, facing the opposite direction, blocking 200 yards of vital runway length with its right wing protruding over and blocking part of the width of the runway, and the left undercarriage collapsed, making that much length unusable.

Dame fortune was still on our side. The “Tenth” did not catch fire; its bomb load intact; otherwise, not only the mission would have been in danger of being scuttled but the numerous aircraft on the airfield may have been blown up—imagine the nine of us, waiting on the tarmac, four having two four-thousand-pounders each and the other four with eight one-thousand pounders, blowing up like a chain reaction of fireworks on “Diwali” — the Indian festival of lights!!

Excitement of the crash and fear of the explosions having evaporated, the nine pairs of air-crews huddled together near our aircraft for the preliminary briefing—the “Tenth” crew, having been sent to the medics for a check up.

“I don’t think you boys can take-off on your mission tonight,” that was the Base Commander (BC) giving his conclusion of the crash site. Sure, it was a decision to be taken before the final word….. ‘go’ or ‘abort’.

We asked all eight sets of air-crews to go to the nearby briefing room, secure in all respects and with lights on inside! The lead crew accompanied the BC to the accident site. After visual inspection and few rough measurements, quick calculations were made on the computer. The expected surface temperature and humidity, and the wind direction and speed, at the time of take-off, the usable length of the runway after lining up alongside the right wing-tip of the “Tenth”, the total all-up weight that the aircraft would be carrying, were all taken into account. It was calculated that we should be able to achieve the “unstick” speed and get airborne, but landing back, in case of an emergency after take-off, was out of the question. Care will have to be taken to “sit” on the brakes, open full power, and then let go…….for the takeoff.

The Briefing

Accepting the importance of the mission, the secrecy involved and the calculated risks, we returned to the briefing room. The lead pilot gave instructions about take-off procedure, as decided, emphasizing, with the help of a blackboard, on the line-up, brakes and full power for takeoff before rolling. The goose-neck flares will again be there, but this time to mark the end of the runway. Strict and complete RT silence until the first attack goes into affect over the target. Complete blackout of all aircraft lights—except the use of a torch for map-reading.

“The TI [target-indicator] marker aircraft with flares and two target-marking bombs, call-sign ‘Tango-India’, will commence its take-off roll sharp at Zero-Zero-One-Six hours,” the lead pilot was now giving the order of battle with all of the pilots jotting down on their knee pads.

“Four minutes thereafter, that is, at Zero-Zero-Two-Zero hours, Victor One, which is Ahlu and me, will roll.” The leader paused, looked at all of the other pilots, and pointing at each one, by turn, he continued, “You, Victor Two, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 will commence rolling at one minute intervals thereafter. ‘Tenth’ being out, there will be no standby.”

“Any questions?” he queried.

“What is the target,” asked a young new navigator of Victor Seven.

“All in good time” retorted the leader, “but remember, your flight plan will give the pre-calculated time over target (TOT). Each one of you is to ensure that you clear the target sharp immediately after that time to make way for the other following you.”

“Victor Eight since you will be the last; you can have a vale of a time playing hide-and-seek with the enemy.” Humor had not been lost, and all had a hearty laugh at the expense of Victor Eight. The last is always in the most difficult situation—the enemy having been alerted by then will try their best to catch at least the last.

“A last warning!” concluded the leader, “Do not attempt to use any portion of the 200 yards of the unusable runway for takeoff under any circumstances. And good luck.”

In the meantime all of the nine aircraft were being refueled. All pilots were asked to go to their aircraft and ensure that the refueling stopped only when the tank started to overflow. Every drop was critical; it may mean safe return and landing at “Charlie” or bailing out short of that place because of dry fuel tanks. For the same reason, after refueling, the aircraft were towed by tractors to the take-off point and parked in the order of take-off. While that was going on, I laid down on the briefing table to relax.

I had now been up for almost 20 hours and had not met my family since the morning of the 12th. I was called at short notice from “Sierra” for the operations against Pakistan and had not been inside a Canberra since February of the year.

On arrival at the Op base, I had arranged for my family to stay with a brother officer’s family, and requested the Commanding Officer (CO) for a “handling” sortie. Aircraft hours had to be conserved, so the answer was a curt ‘no’. My first “handling” sortie, after six months of having flown a Canberra, was on September 7th over Sargodha in Pakistan!

“Where are you boys off to, tonight?” It was the Base Commander again who appeared from nowhere and broke my chain of thought.

Normally, a commander of the ‘staging’ or ‘jumping’ base was discreet enough not to ask such questions. “Ask no questions and you will be told no lies”, was a well-adopted principle under these circumstances.

“Well, Sir, even my CO and the Station Commander and the other air-crews are unaware of this,” I very hesitatingly but politely and tactfully evaded the answer, and added, “the remaining air-crew will be informed at the final briefing just before take-off”.

The BC got the message and after some small talk, and cursing having to find his way in the dark, left me with my thoughts. But the thoughts were now replaced with the “plan”.

All the air-crews who were actually flying had re-assembled. The briefing room was now pulsating with low-level tension. After doors were closed and it was ensured no other person except the mission air-crews were present, I opened my briefcase, retrieved the nine flight plan copies, and distributed one to each navigator. I also retrieved the target outline plan from my bag and placed it on the large planning table. All huddled around the table and craned their necks to see the target. Both, the flight plan and the outline plan did not name the target.

“Gentlemen!” I felt my voice croak with excitement, nervousness, tension, and some anticipation of the unknown. “Tonight, we undertake a mission which the enemy considers impossible, and, it will, therefore, be the biggest surprise of this war, which they will ever have, when we show them that nothing is impossible for this ‘elephant with the twisted tail’.” That was a reference to our squadron insignia.

“This is also the reason for the excessive secrecy,” I continued, “and once the target is given out, no one is to leave this area or talk to anyone about it until a successful return from this mission. Use the toilets now, if you wish.” This last remark had a double meaning…….Silence. I could feel the excitement and the tension growing.

“Our target for tonight is PESHAWAR.” I paused for it to sink in and awaited the anticipated reactions.

“Hurrah!” said one.

“Oh! No,” sighed a second.

“Impossible!” concluded a third, still not believing his ears.

“A one-way ticket!!” was the defeatist attitude of another.

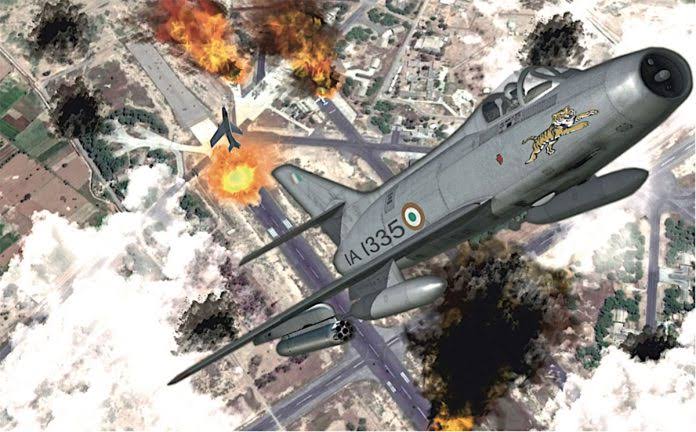

The excitement, the tension, the nervousness, and the fear were everywhere. I could feel and sense what each was thinking. On many occasions this target had been discussed in moot exercises and rejected as “impossible” for the Canberra with her limitations. It was always felt that Canberra could only reach and return from Peshawar by flying at height, definitely not below 20,000 feet; and which would make them vulnerable and virtual “sitting ducks” for the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) Starfighters, with their night-flying and all-weather capabilities, and which were armed with sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missiles. The anxiety and fear of the air-crews was palpable, conspicuous and clearly the same as it was in that afternoon with my pilot and me at Op HQ.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“We plan to attack Peshawar tonight with four Canberras carrying 8×1000 pounders.” The opening announcement of the Bops had come as a shocking surprise to both of us in Op HQ.

“All will fly at about 20,000 feet and use the ‘blind-bombing’ radar to track and bomb the target.” he explained and continued, “We are aware of the risks involved, but those are acceptable. Your squadron is at liberty to select air-crews, but the target must not, and I repeat, must not be disclosed to anyone outside this hall until the time of final take-off for the target. Ahluwalia will prepare the flight plan and hand over to each crew copies of the same only shortly before take-off. Remember, secrecy for the success of this mission is imperative.

Any questions?”

Thank God! The Bops had opened an escape route.

“Sir, what is the exact target in Peshawar?” I queried.

“Everything—the flying control, fuel-dump, bomb-dump, PAF Headquarters, PAF Officers Mess, aircraft, hangars—everything, without any limit,” he proudly emphasized.

“Sir, I understand the success of this mission means a lot to us. But the plan is certain to end in failure even before we reach the target,” – I very courageously countered the Bops plan. I could sense the CAS and the AOC-in-C staring at me, but I dare not look at them at this stage.

“Moreover,” I continued, “the 32 thousand pounds against such vast and varied targets would be against the principle of economy of effort and, even if we do manage to drop them over the targets, the damage is not likely to hurt them much, unless we achieve direct hits, which is highly improbable though not impossible.”

It was now apparent that the Bops had not done his homework and was becoming fidgety. Though he was also a Canberra pilot, but was trained in high-level bombing—both visual and blind. That was his limitation. I was trained in the high-level bombing role in the UK, and in the low-level interdiction role in India. Rather, I was one of the protagonists, proponents and pioneers of evolving, practicing and teaching performance in this role, since I believed, like many others, in the invincibility of the Canberra in this role, particularly, at night.

I pressed home my advantage, “We want to take them by surprise and hit them so that they feel it. The targets are OK, but the hit is neither hard nor is surprise assured. We will be on their radar while still in our own territory, and their Starfighters would be ready for us before we are even anywhere near Peshawar. This will be a suicidal mission for us not a surprise to them.”

Stunned silence greeted me instead of applause. The speed with which I countered the plan—a plan prepared at the “highest” level—a plan being shredded to pieces, surprised both me and my pilot who was watching in awe and amazement…….. and new-found respect. He may be the lead pilot, but as the lead navigator, I had a task to get him to the target at the right time, and as lead bombardier I had a task to deliver the load on the target, at the right place, against all odds, and make every endeavor to come back home……..safely.

“Any plan you have in mind.” It was the CAS. For the first time I looked at him, my palms sweaty.

“No, Sir,” I replied meekly, but went on to hurriedly add, “we were neither aware of the target nor its importance. Given about an hour, a more viable and acceptable plan could be worked out. However, before that we would like to have the defenses at and around Peshawar.”

The CIO recounted the anti-aircraft gun defenses and the location of the base of the Starfighters of which the PAF had only four serviceable and all on Operational Readiness Platform (ORP) round the clock.

“You bought yourself an hour. Go ahead and let us know when you are ready with the plan,” the AOC-in-C decisively ordered and left the hall with the CAS.

The Bops was an old friend, a rank senior to me, though we had always been in different squadrons. Being let down like this, in the presence of the two ‘top brass’ of the IAF, would not be a palatable thing to anyone. At the same time, being pushed into a suicidal mission because of the unfortunate and ill-conceived plan was not my cup of tea.

“No hard feelings, Sir,” said I to the Bops, while settling myself down to plan.

Excerpted from Airborne to Chairborne : Memoirs of a War Veteran – Aviator – Lawyer of the Indian Air Force

Gp Capt Ahluwalia was mentioned in dispatches for his participation in the war. He is currently settled in California, USA.