The slowest train journey in India

Nobody uses the Nilgiri Mountain Railway to get from A to B, but for the sheer joy of riding in a train that passes through 16 tunnels, 250 bridges and 208 serpentine curves.

By Charukesi Ramadurai

The Bollywood movie Dil Se may have opened to a lukewarm response at the Indian box office, but one of the song sequences from the movie remains a favourite melody 25 years on. Chaiyya Chaiyya isn’t just memorable just for its catchy tune, but also because it was shot entirely on top of a moving train. Indian heartthrob Shah Rukh Khan pranced around with a group of backup dancers as the train chugged slowly across lush hilly terrain, past tea plantations and over tall viaducts, steam billowing from the old-fashioned engine.

I, too, have travelled on this very train, although my journey was far more comfortable and less precarious than Khan’s. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway (Nilgiri translates to “blue mountain” after the bluish hue the sun casts on the hills), which locals refer to as NMR or more fondly as the “toy train”, is a delightful example of the cliché about the journey being the destination.

Running though Tamil Nadu State, the train is the slowest in India due to an extremely steep gradient on the route. It takes nearly five hours to cover a distance of 46km, climbing from the town of Mettupalayam at the foothills of the Nilgiris up to the hill town of Udhagamandalam – amended by British tongues to Ootacamund and then shortened by Indians to Ooty. The downhill ride back cuts an hour, but the journey by road takes just a fraction of that time.

The Nilgiri Mountain Railway connects Metupalayam and Ooty in the southern state of Tamil Nadu

Clearly, nobody uses the NMR to get from A to B, but for the sheer joy of riding in a train that passes through 16 tunnels, 250 bridges and 208 steep curves on the richly biodiverse Western Ghats mountain range, a Unesco World Heritage site.

Armed with a first-class ticket that cost Rs 600 (about £6), I boarded the blue train at Ooty on a chilly morning, eager to experience this quintessential Nilgiris experience. (A second-class ticket is less than half the price, but without the light cushioning on the seats).

When you get into the train, it is like you enter another dimension

D Om Prakash Narayan, senior public relations officer with Southern Railway, which operates the train, told me, “When you get into the train, it is like you enter another dimension.”

I could see what he meant when I boarded the tiny coach. Families with children were crowded around the boxy windows, waiting for the promised views of the Nilgiris. There was a palpable sense of excitement among passengers, with everyone in a holiday mood, cheering and clapping when the train went through dark tunnels.

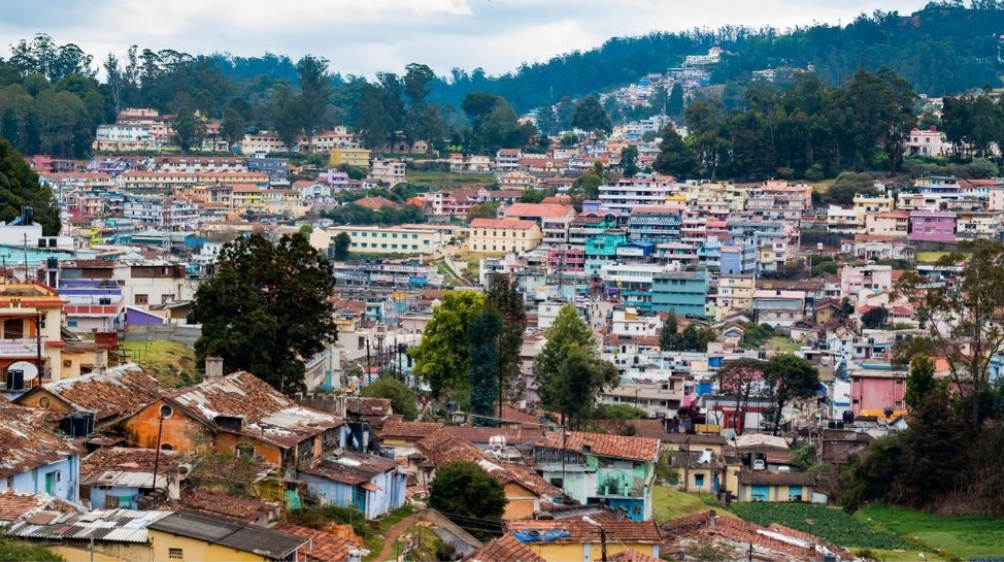

Located at an altitude of 2,240m, Ooty was founded as a summer resort for the British Raj.

Ooty is one of India’s oldest hill stations – these towns at higher elevations were the summer retreats of the British Raj when they needed to escape the stifling heat of the plains – and remains popular among Indian tourists looking for a cool holiday or honeymoon. Today it’s a crowded little town, with vestiges of colonialism hidden within the chaos of urban India. But as we left Ooty behind, reminders of the British Raj began to make an appearance, with station names like Lovedale, Wellington, Adderly and Runnymede.

“It all feels unchanged from the British times, like time has stopped here,” said Sharanya Sitaraman, who recently travelled on this train with her family. “We almost could imagine European ladies with fancy hats getting off the train at these small stations.”

Remnants of the Raj are particularly seen in the colonial design of several old buildings across the Nilgiris: offices, bungalows (some of which are now boutique hotels) and churches. The colonial feel is so evocative that Coonoor station, just an hour down from Ooty, became part of the fictional town of Chandrapore in David Lean’s 1984 film adaptation of EM Forster’s novel, A Passage to India.

We almost could imagine European ladies with fancy hats getting off the train at these small stations

“People on this train still see the same things that people saw more than 100 years ago,” said retired journalist D Radhakrishnan, who reported for decades from the Nilgiris region.

Coonoor station formed the backdrop for David Lean’s movie A Passage to India, based on E M Forster’s novel

Narayan, a railways veteran of more than 30 years, agrees: “Ooty and Coonoor have been exploited for their natural resources in the name of development, and you see this when you travel by road. But when you travel by this train, it feels like nothing has been touched.”

We passed tea plantations with workers bent over the leaves, and waterfalls that had sprung up after the monsoons. I kept leaning out of the window to see the train’s serpentine twists and turns, keeping my eyes peeled for a glimpse of a stray gaur (Indian bison) or elephant in the thickets. There was incessant activity, with people getting off to stretch their legs and take photographs at the various stations on the way (some are for passengers and others are only to refill water for the steam locomotive). The halt at Coonoor was much longer, allowing the train to change from a diesel locomotive (used for the fairly flat ride until now) to steam, for more power on the slopes.

The restful scenery and the gentle rocking of the train lulled me into a state of near somnolence. At one of the water stops, I fuelled up on piping-hot chai and masala vada (spicy fritters) sold by local vendors – quintessential elements of any train trip in India.

Mangalore-based journalist Subha J Rao, who grew up in the plains near Mettupalayam, has similarly relaxing memories of the train trip from her childhood. “We could actually get off and walk along with the train,” she said. “As adults, we now talk of the romance of train travel, but then as kids, we just enjoyed the experience, even with all the soot and smoke from the steam engine.”

Views from the train take in the many tea plantations in the area

The Nilgiri Mountain Railway, along with the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in West Bengal and the Kalka Shimla Railway in Himachal Pradesh up north, are part of Unesco’s Mountain Railways of India World Heritage listing. All of them owe their existence to the British, who built them as a means of convenient travel to cooler climes during the sweltering summers. But Radhakrishnan was quick to point out, “They brought in the railways entirely for their own comfort, not for the good of Indian people. If they could have taken it back with them, they would have.”

Whatever the intentions, creating this route on this treacherous hill terrain was highly challenging. According to Unesco, “This railway, scaling an elevation of 326m to 2,203m, represented the latest technology of the time.” Narayan explained that the gradient in some parts, such as the stretch between Kallar and Coonoor, is so steep that a unique rack and pinion system has to be used. This means an extra rail with sharp teeth in the middle of the tracks (rack) grips the toothed wheel (pinion) on the coach to prevent slipping and sliding. It was devised by the original Swiss engineering team hired by the Brits to design and oversee the construction. This design is found only in a few other Swiss railway lines today, apart from the NMR, and still works to this day.

Work on the rail line began in 1891 and took 17 years to complete, making this the 115th year since the train started. Ooty itself is gearing up to celebrate a milestone anniversary in 2023, as it is exactly 200 years since British official John Sullivan came across this salubrious hamlet in the hills and added it to the increasing list of Raj summer retreats. That means the NMR has been part of Ooty’s heritage for more than half of its existence.

Apart from the NMR, the rack and pinion system is only found only in a few other Swiss railway lines

According to Radhakrishnan, there have been several plans to shut down this train service due to it being uneconomical. But it is such an integral part of Ooty’s tourism sector that these plans get squashed as soon as they are mooted. “Many people come here only for a ride on this train, and it is impossible to think of Ooty without the NMR,” he said.

When we finally pulled into Mettupalayam, four calm and relaxing hours after leaving Ooty, I recalled something that Rao had told me: “Travel on this train is a throwback to gentler times.”

I found it to be an antidote to the stress and strife of everyday life, and as my own mind slowed to match the speed of the train, it was exactly the kind of throwback I needed.

BBC TRAVEL