The terror weapon, USA used twice : Regret, conflict troubled scientists after Los Alamos test

Tensions were running high at the Trinity site in the early morning hours of July 16, 1945 on the outskirts of Alamogordo, in the western U.S. state of New Mexico.

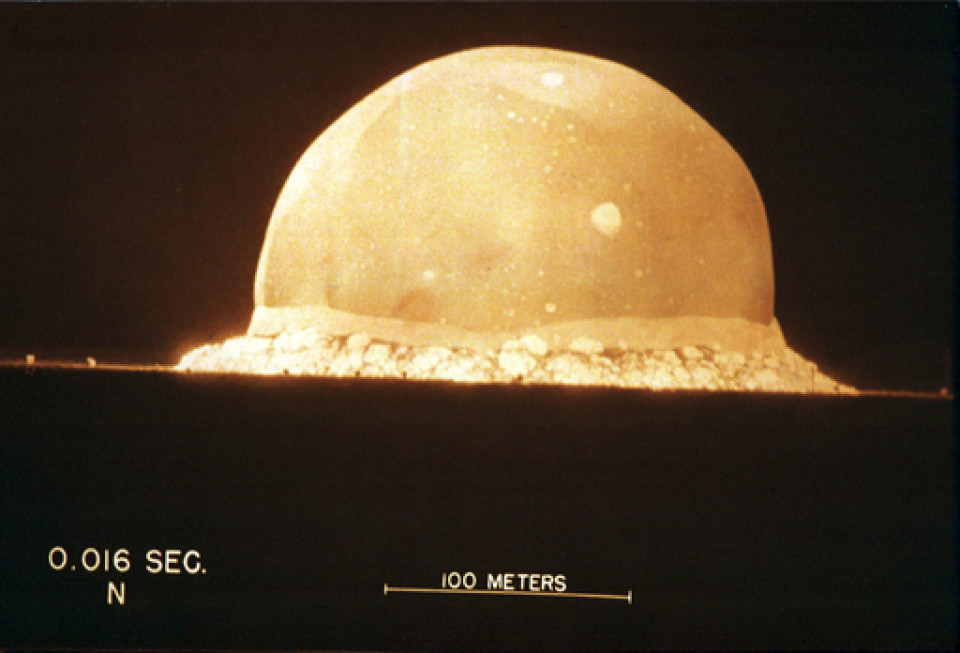

After a thunderstorm delayed the testing of the world’s first nuclear weapon, another “sun” suddenly lit up the night sky — a flash so brilliant it could not be viewed with the naked eye, accompanied by a powerful explosion unleashing radiation that spread out in all directions across the desert landscape.

The first nuclear test in history was a success, thus birthing the dawn of the nuclear age.Looking up at the huge mushroom cloud, Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb” and director of the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos Laboratory, was reminded of a line from Hindu scripture: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”Most scientists involved in the project to develop the atomic bomb marveled at the achievement and applauded the bomb’s tremendous power. But not everyone was elated that day.

At sunrise, when news of the “successful experiment” broke at Los Alamos, jubilant celebrations were held in various locations in the artificial town built in New Mexico for the express purpose of constructing the bomb.

Richard Feynman, at the time a 27-year-old theoretical physicist, recounted an exchange he had with his senior colleague Robert Wilson immediately after the test, sharing the story in a lecture he gave at the University of California three decades later.

Rather than showing his delight with the success of the nuclear test, Wilson was despondent.

After the test, “there was tremendous excitement at Los Alamos,” Feynman said. “Everybody had parties, we all ran around…But one man I remember, Bob Wilson, was just sitting there moping.””I said, ‘What are you moping about?’ He said, ‘It’s a terrible thing that we made.’ I said, ‘But you started it.

You got us into it.'”Indeed, it was Wilson who had recruited Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize in physics after the war, to help develop the atomic bomb with the team at Los Alamos.

According to the lecture transcript, before the Los Alamos Laboratory became fully operational in 1943, Wilson, who was working at Princeton University, visited Feynman in his research room to talk with him about the secret project he was working on.

He explained that he got funding to work on a process to produce enriched uranium to use in an atomic bomb.”He told me about the problem of separating different isotopes of uranium to ultimately make a bomb.

He had a process for separating the isotopes (different from the one ultimately used) that he wanted to try to develop.”There was a 3 p.m. meeting to discuss the process, and Wilson said he would see Feynman there.

Mention of the project, of course, was strictly forbidden, but Feynman, whom Wilson had confided in, immediately responded. “I said, ‘It’s all right that you told me the secret because I’m not going to tell anybody, but I’m not going to do it.’

“But afterword, Feynman said he went back to work on his thesis — “for about three minutes.” He recalled being torn at the time, saying he began pacing the floor, lost in thought.”The Germans had Hitler and the possibility of developing an atomic bomb was obvious, and the possibility that they would develop it before we did was very much of a fright.

So I decided to go to the meeting at three o’clock.”Nazi Germany’s sudden attack on Poland plunged the world into the turmoil of World War II.

After the conquest of Paris, the Nazis continued their bloody land battles with the Soviet Union and engaged in fierce fighting against American and British forces, all while massacring Jews sent off to concentration camps.

While under enormous distress over the situation unfolding in Europe, Wilson asked Feynman, whom he trusted, to help in developing a process to separate the fissile material from uranium.

And it was Wilson’s encounter with “the father of the atomic bomb” at the University of California that led to him getting involved in the Manhattan Project in the first place.

QMartin Sherwin, the American historian who coauthored the 2005 biography “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” recorded an interview of Wilson before the latter’s death in 2000. Sherwin died in 2021.

“As a graduate student, I knew him because I went to his seminar. I went to his course, talked to him, knew his students. He was a very accessible person,” Wilson said of Oppenheimer, based on testimony maintained by Sherwin’s estate.”I had a project at Princeton that was just closing down. It was a project to separate isotopes and represented a group of perhaps 20 people. (Oppenheimer) was very anxious to get that group to come out en masse to help at the laboratory (at Los Alamos).

“For Oppenheimer, who wanted to mass produce uranium-235 — the raw material for the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan — Wilson’s research, in fact, represented a godsend.

In March 1943, Wilson was persuaded to visit Los Alamos for the first time, after which he worked together with Oppenheimer to develop the bomb.

But two years and four months later, on the day of the successful nuclear test, Wilson was horrified by the “atomic fire” unleashed on earth. They had done something irreversible, he lamented.

The United States dropped an atomic bomb over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, killing an estimated 140,000 people by the end of that year. Three days later, a second one was detonated over Nagasaki, with an estimated 74,000 people dead there by year’s end.

Nuclear bombs continue to torment many hibakusha atomic bomb survivors to this day.Some of the scientists who produced the “devil’s weapon” had pangs of remorse and deep conflicts of conscience. Wilson and Feynman’s testimonies are just two of the backstories behind the Manhattan Project.

Feynman further said of Wilson’s reaction after the nuclear test: “You see, what happened to me — what happened to the rest of us — is we started for a good reason, then you’re working very hard to accomplish something, and it’s a pleasure, it’s excitement.

And you stop thinking, you know; you just stop. So Bob Wilson was the only one who was still thinking about it at that moment.”