The underestimated PM Narasimha Rao

Reforms, civility and temper of political discourse thrived under him

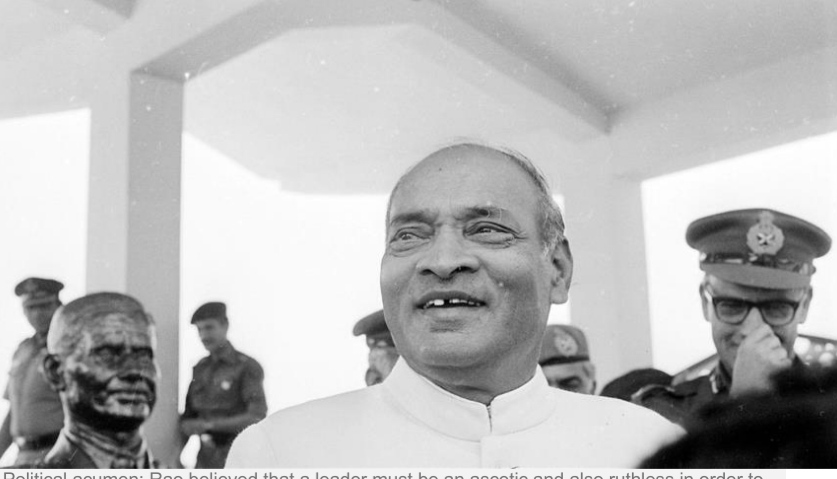

Political acumen: Rao believed that a leader must be an ascetic and also ruthless in order to succeed. He possessed elements of both.

Former foreign secretary and senior fellow, centre for policy research

June 28 marked the 99th birth anniversary of PV Narasimha Rao, one of India’s finest prime ministers. I had the privilege of serving as Joint Secretary in charge of External Affairs, Defence and Atomic Energy in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) during the early part of his tenure.

I left for Mauritius as High Commissioner in 1992, just as the demolition of the Babri Masjid was igniting communal fires across the country. In the year and a half I spent working with him, I came to respect his political acumen, deep scholarship and his innate sense of humour. He had the quality of lateral thinking.

He would listen to my briefing on any particular issue, and unexpectedly come up with an observation that related to the subject only tangentially but in fact, enriched one’s understanding.

He would often explore the more subtle nuances embedded in a situation, helping craft a more finely honed response. He delighted in political horse-trading at home but with a tact and delicacy which cloaked the messy grit underneath.

What I found impressive was the affable relations he maintained with the entire spectrum of opposition leaders. They, in return, treated him with respect and congeniality, despite political contestation.

What a stunning contrast to the sharp political polarisation one witnesses today. There is no comparison to the civility and temper of political discourse which thrived under Rao.

His masterstroke was having the then leader of Opposition, Atal Bihari Vajpayee lead India’s delegation to the UNHRC to defend India’s case on the J&K issue. It was a display of our democratic credentials and sense of national unity and purpose which has rarely been in evidence since then.

I had a ringside view of the momentous developments leading to the adoption of economic reforms and liberalisation and Rao’s moments of hesitation interspersed with unusual determination.

Once he was convinced that economic revival and prosperity depended upon taking what seemed a risky political gamble, he did not look back. He would sometimes find it difficult to assume the role of a ‘salesman’ of India’s reforms but performed admirably nevertheless.

For his first visit to Japan, in June 1992, a number of important engagements had been programmed. There was to be a luncheon meeting with Japanese CEOs at which Rao would make a speech introducing India’s landmark reforms and invite Japanese investment.

A number of key business leaders would have individual meetings with him. The PM was to arrive in Tokyo early that morning and after the ceremonial welcome at Akasaka Palace, would have a brief meeting with his counterpart, though official-level talks would follow later.

A couple of days before the visit, I was told to convey to our embassy in Tokyo that the PM would not be able to address the luncheon meeting nor would he receive some of the CEOs later during the day. It was suggested that perhaps another senior member of the delegation could do the honours instead.

Despite persuasion from the then Principal Secretary and the Foreign Secretary, the PM was apparently not convinced that these items on his visit agenda were of critical importance.

Having served in our Tokyo embassy earlier, I tried to salvage the situation. If there was something really important that I needed to discuss with him, I would call at his residence early in the morning.

I called to tell him that the cancellation of his programme would be misunderstood in Japan and would result in a setback to our efforts to promote investment. His reply was that he was India’s PM and not a salesman and could not somebody else do the job.

He also complained that he would have to undertake these engagements soon after a long flight. I took care of the latter complaint by saying we could reschedule the flight so that he arrived the night before, have a full night’s rest and be ready for the day’s engagements.

I launched into an impassioned argument about why the outreach to the Japanese business community had to be at his level. Though not entirely convinced, he was persuaded to go along and the visit was a great success.

There were several occasions when I would intervene with him on some issue or the other. Never once did he make me feel that I was overstepping my role. He sometimes concurred with what I had to say, sometimes not, but he always heard me out.

PM Rao would sometimes come up with unexpected comments. Once, out of the blue, he asked me what attributes a leader in India must possess to succeed. I was about to make some inane reply when he answered his own question: ‘A leader must be an ascetic but also ruthless in order to succeed.’ He certainly possessed elements of both.

When he died in December 2004, I was Foreign Secretary. I went to pay my respects at his residence, where his body was laid out on the floor in one of the rooms. It was early afternoon but there was not a soul around except for a lone policeman sitting on a chair reading a newspaper. One of India’s finest prime ministers and a thoroughly cultivated human being certainly deserved better