UNESCO : Great Barrier Reef should be listed as ‘In Danger’

The Great Barrier Reef has held World Heritage status since 1981

Australia’s government has lashed out after a United Nations report claimed it had not done enough to protect the Great Barrier Reef from climate change.

UN body Unesco said the reef should be put on a list of World Heritage Sites that are “in danger” due to the damage it has suffered.

Key targets on improving water quality had not been met, it said.

Environment minister Sussan Ley said UN experts had reneged on past assurances.

She confirmed that Australia planned to challenge the listing, which would take place at a meeting next month, saying: “Clearly there were politics behind it; clearly those politics have subverted a proper process.”

The World Heritage Committee is a 12-nation group chaired by China, which has had a vexed diplomatic relationship with Canberra in recent years.

“Climate change is the single biggest threat to all of the world’s reef ecosystems… and there are 83 natural World Heritage properties facing climate change threats so it’s not fair to simply single out Australia,” said Ms Ley.

Environmental groups say the UN’s decision highlights Australia’s weak climate action, however.

“The recommendation from Unesco is clear and unequivocal that the Australian government is not doing enough to protect our greatest natural asset, especially on climate change,” said Richard Leck, Head of Oceans for the World Wide Fund for Nature-Australia.

media captionThe second bleaching is causing concerns over the reef’s long term health.

The latest row is part of an ongoing dispute between Unesco and Australia over the status of the iconic site.

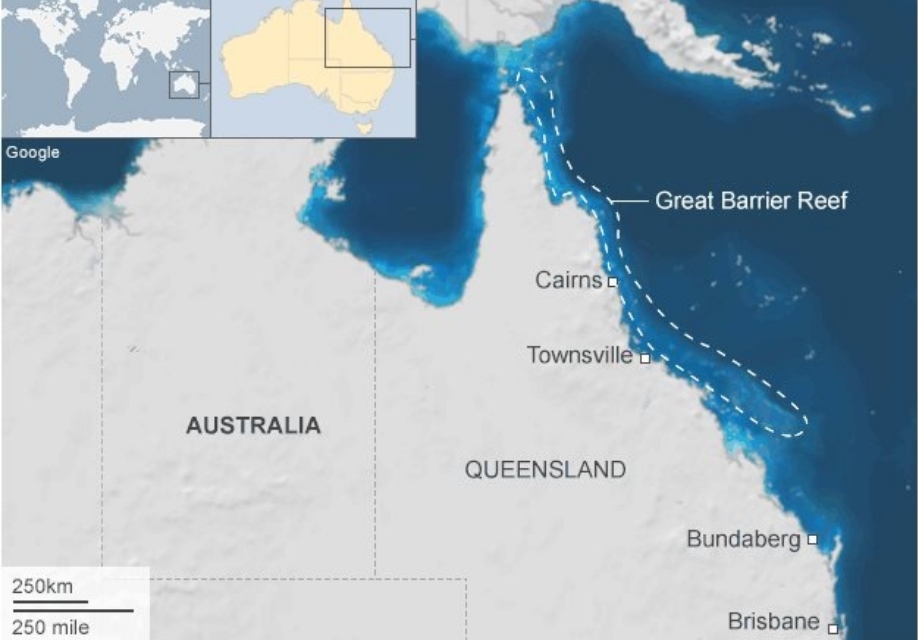

The reef, stretching for 2,300km (1,400 miles) off Australia’s north-east coast, gained World Heritage ranking in 1981 for its “enormous scientific and intrinsic importance”.

After Unesco first debated its “in danger” status in 2017, Canberra committed more than A$3 billion (£1.bn; $2.2bn) to improving the reef’s health.

However, several bleaching events on the reef in the past five years have caused widespread loss of coral.

Scientists say the main reason is rising sea temperatures as a result of global warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels.

In 2019, Australia’s own reef authority downgraded the reef’s condition from poor to very poor in its five-year update.

But Australia remains reluctant to commit to stronger climate action, such as by signing up to a net zero emissions target by 2050.

The country, a large exporter of coal and gas, has not updated its climate goals since 2015. Its current emissions reduction target is 26-28% of 2005 levels by 2030.

These have been a tough few months for Australia and its climate change policy.

International pressure has been mounting on Scott Morrison’s government to pledge net zero emissions by 2050 and the prime minister has time and time again refused to commit – including as recently as last week at the G7 meeting in the UK.

In his address to US President Joe Biden’s virtual climate conference with global leaders in April, the prime minister said the country will “get there as soon as we possibly can,” adding that “for Australia, it is not a question of if, or even by when, for net-zero but, importantly, how”.

That in itself is at the heart of the problem. The “when” is as crucial as the “how” when it comes to climate change.

Scientists and global leaders say Australia is not doing enough or going fast enough.

The Great Barrier Reef row between Unesco and the Australian government is not new, but it will be quite embarrassing if the country’s World Heritage Site is downgraded to the “in danger” list.

It’s another reminder that if Australia does not get serious about tackling climate change with clear and decisive measures, this will affect its standing in the world, not just diplomatically and economically but culturally too.

If the reef is downgraded, it will be the first time a natural World Heritage Site has been placed on the “in danger” list primarily due to impacts of climate change.

Listing a site as “in danger” can help address threats by, for example, unlocking access to funds or publicity.

But the recommendation could affect a major tourism destination that creates thousands of jobs in Australia and was worth A$6.4bn prior to the pandemic.