What is NATO and what role does it play in the Russia-Ukraine crisis?

At nearly 73 years old, NATO now has 30 members, including three Baltic states that were once directly part of the Soviet Union

Underpinning the diplomatic stand-off between Russia and the West is President Vladimir Putin’s key demand — he doesn’t want Ukraine to ever be allowed to join NATO.

Formed in the aftermath of World War II with the aim of achieving lasting peace and to provide collective security against the Soviet Union, today NATO is the world’s biggest and most powerful military alliance.

Russia maintains that after the Cold War, NATO promised it would not expand eastward to the former Soviet states.

However, the alliance is open to any European nation that wants to join and can meet the requirements and obligations.

More than a dozen countries from the former Eastern bloc, including three former Soviet republics, have joined the alliance over its nearly 73-year history.

It currently has 30 members.

While Ukraine is not a NATO member, Kyiv is a close partner and was promised eventual membership at a NATO summit in 2008.

Recently, Russia has become particularly alarmed by NATO’s increasing closeness with Ukraine, which is seen by Moscow as a buffer between it and the West.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said earlier this month that it is “absolutely mandatory to ensure Ukraine never, ever becomes a member of NATO”.

So what exactly is NATO and what is its role in the world today?

NATO does not have any troops in Ukraine, but is working with the country to modernise its armed forces.

Who is involved?

In 1949, the United States, Canada and 10 Western European countries were the first to sign the NATO Treaty.

The treaty commits allies to protect each other, ensuring that “the security of its European member countries is inseparably linked to that of its North American member countries”.

Turkey and several more European countries were the next to join, which prompted the Soviet Union in 1955 to form a counterbalance alliance with several communist countries in Eastern Europe known as the Warsaw Pact.

But when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 so too did the pact, sending many members — including Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary — NATO’s way.

Ukraine is largely surrounded by European Union nations on one side, and Russia on the other.

The United States is, without doubt, the biggest and most influential member, but NATO’s decisions are made by consensus and there is no majority voting of any kind.

This means that Albania, for example, has a veto just as final as Washington’s.

Given its location between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Australia is not a member of NATO — the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Australia has, however, in recent years strengthened relations with the alliance to address shared security challenges.

Australia is referred to as one of NATO’s “partners across the globe” and has assisted in NATO-led defence capacity-building efforts in Afghanistan and is regularly involved in military exercises open to partners.

It is unlikely, however, that Australia would provide military assistance should Russia invade Ukraine.

Defence Minister Peter Dutton has said he does not expect a request for troops to be deployed.

Space to play or pause, M to mute, left and right arrows to seek, up and down arrows for volume.

The EU’s Ambassador to Australia warns of a looming ‘crisis’.

What does NATO do?

In addition to military support, the organisation provides a forum for dialogue and cooperation across the Atlantic.

On any given day, hundreds of officials meet at the headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, to exchange information and help prepare decisions.

NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg chairs the alliance’s prominent meetings, but he doesn’t order the allies around.

His job is to encourage consensus and speak on their behalf publicly as a single voice representing all 30 members.

While the Soviet Union is long gone, NATO continues to see Russia as a security threat and to offer protection to concerned member states near Russia’s borders.

But over time, the alliance has also taken on wider roles.

At the heart of NATO’s founding treaty is the principle of collective defence.

This is why out of the treaty’s 14 articles, the backbone of the alliance is Article 5.

Article 5 states that if one ally is a victim of an attack, it is considered an attack against all members.

It essentially gives all smaller countries protection under the US and allows them to access equipment and expertise they can’t afford alone.

NATO actually has no weapons of its own, instead, they are owned and brought in to operations by the member countries, mostly at their own cost.

Former US president Donald Trump had increasingly undercut the alliance, saying that the US paid “far too much” and the other members contributed “far too little”.

He even refused to reiterate support for Article 5, leaving the alliance shaky.

Member countries have since committed to spend 2 per cent of their respective GDPs on defence expenses by 2024.

Although the US is the most influential member, NATO’s decisions are made by consensus.

The alliance in action

On the ground, NATO has notably helped to keep peace in the Balkans, conducting its first major crisis response operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995.

It also sent troops to combat the Taliban-led insurgency in war-torn Afghanistan — the alliance’s biggest-ever operation, launched after the United States triggered its “all for one and one for all” common defence clause in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

It was the first time Article 5 was activated.

After nearly two decades, in April 2021, NATO decided to withdraw all allied troops from Afghanistan within a few months and has since suspended all areas of cooperation with the country.

At the request of Turkey, NATO also put collective defence measures in place in 2003 during the crisis in Iraq, and in 2012 in response to the situation in Syria, it deployed Patriot missiles.

The US has the largest number of military personnel out of NATO members, with around 1.35 million troops.

It is followed by Turkey with just over 445,000 personnel.

Russia has intensified military drills amid tensions with the West over the build-up of an estimated 100,000 Russian troops near Ukraine.

What is NATO’s role in Ukraine?

In response to Russia’s build-up of more than 100,000 troops on Ukraine’s borders, NATO allies are putting forces on stand-by.

What can Russia gain by invading Ukraine?

Russian President Vladimir Putin has long believed that Russia and Ukraine should be reunited as one country.

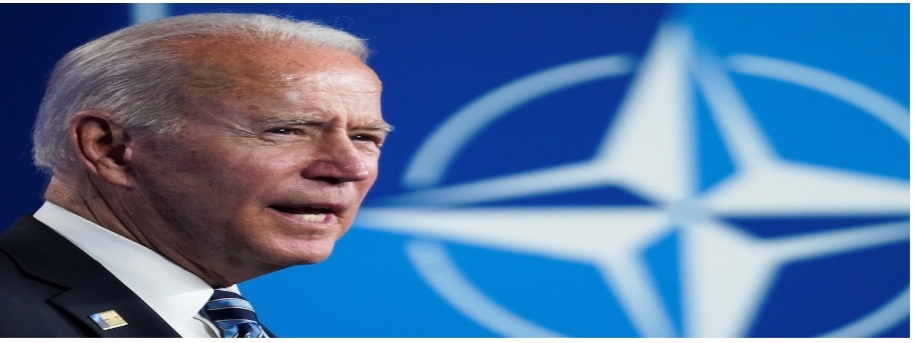

The US has said it will not send American or allied troops to fight Russia in Ukraine, but President Joe Biden has ordered 8,500 to be on heightened alert for deployment to the Baltic region.

The alliance has no obligation to defend Ukraine, so for now, it is working with the country to modernise its armed forces.

It is concerned about a potential spillover from any conflict with Russia, particularly in the Black Sea region, where Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, and in the Baltic Sea.

Canada is operating a training program in Ukraine, while Denmark is also stepping up efforts to bring Ukraine’s military up to NATO standards.

The US, Britain and the Baltic states are sending weapons to Ukraine, including anti-tank missiles, small arms and boats.

Turkey has sold drones to Ukraine that the Ukrainian military has used in eastern Ukraine against Russian-backed separatists.

However, Germany is against sending arms to Ukraine.

Berlin has instead promised a complete field hospital and the necessary training for Ukrainian troops to operate it, worth about $US6 million ($8.5 million).

The alliance has also said it will help Ukraine defend against cyber attacks and is providing secure communications equipment for military command.

A satellite image of a Russian troop build-up at Klimovo, Russia, 13 kilometres north of the Russia-Ukraine border.

Next NATO negotiations

Washington has made clear that Russia’s demands that NATO pulls back troops and weapons from Eastern Europe and bar Ukraine from ever joining are non-starters.

US options if Russia invades Ukraine

Removing Russia from an international financial system, blocking the country from the US dollar and going after high-ranking officials and their families, including Vladimir Putin’s suspected girlfriend, are all options being floated if Russia invades Ukraine.

But it says it is ready to discuss other topics such as arms control and confidence-building measures.

Russia has responded to the United States’ formal rejection of its core demands, saying it did not leave much room for optimism but dialogue was still possible.

NATO has offered more talks with Moscow in the format of the NATO-Russia Council in Brussels to find a solution.

NATO allies are also discussing whether to increase the number of troops rotating through eastern Europe.

They will focus on the issue when allied defence ministers meet for a scheduled meeting in Brussels in mid-February.

NATO has four multinational battalion-size battlegroups, or some 4,000 soldiers, led by Canada, Germany, Britain and the United States in Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Poland.

The troops serve as a “trip-wire” for the 40,000-strong NATO Response Force (NRF) to come in quickly and bring more US troops and weapons from across the Atlantic.

The NRF is based on a rotational system where allied countries commit land, air, maritime or Special Operations Forces (SOF) units for a period of 12 months.

The biggest decisions may not come until June, when NATO leaders are due to meet for a summit in Madrid.

They are expected to agree to a new master plan, called a Strategic Concept, in part to cement NATO’s focus on deterring Russia.