Where humans don’t fear leopards

By Sugato Mukherjee5th May 2022While leopards have been targeted for poaching or revenge killings in much of India, the people of Bera continue to live in peaceful cohabitation with the graceful felines.

ur 4×4 negotiated through sparse woodlands and eventually heaved its way up a steep incline before jolting to a stop. A vast, boulder-strewn landscape rolled out below us. This undulating terrain is the region of Gorwar, which stretches along the edge of the Aravalli Range in south-west Rajasthan.

We were on an early morning safari in the village of Bera, a three-hour drive from the tourist mecca of Udaipur, to witness an anomaly: human-leopard cohabitation, with zero conflict.

Leopard numbers have been on the rise in India in recent years, with a 2018 report estimating the population at 12,852. Human-animal conflicts and mutual encroachments in a densely populated country have been inevitable. The graceful felines have been poached for their luscious coats and other body parts that fetch huge prices in illegal markets. They have been killed by groups of villagers, a retaliatory measure for attacks on precious livestock or simply out of fear when the large cats have strayed into human spaces.

In the first six months of 2021, 102 leopards were poached and another 22 were killed by villagers. Between 2012 to 2018, 238 leopards were killed in the state of Rajasthan alone. And media reports of leopard attacks on humans have been alarmingly frequent.

In this remote, pastoral corner of Rajasthan, however, it has been a continuous saga of peaceful cohabitation between the leopards and the Rabaris, a semi-nomadic shepherding community that migrated to India from Iran more than a millennium ago. It is estimated that about 60 leopards, along with hyenas, desert foxes, wild boars, antelopes and other smaller animals, currently prowl this land.

Visitors go on leopard safaris in the Indian village of Bera (Credit: Sugato Mukherjee)

The free-roaming big cats are known as Jawai leopards, named after the dam built on the Jawai River in 1957. The pristine body of water is the principal water source for the surrounding towns and villages, and an important wildlife habitat.

That morning, Pushpendra Singh Ranawat, a keen conservationist with a wealth of on-the-ground knowledge, steered me into the inner recesses of this “Leopard Country” that has one of world’s highest leopard densities within its 25km radius around Bera. “There has not been a single incident of poaching in at least five decades,” he said. “And importantly, leopards here do not consider human presence as a potential threat.”

“That’s pretty remarkable,” I said with surprise.

“We will soon see,” said Ranawat, as he scanned the rock-ridden landscape with his field glasses. We spent the next few minutes in silence, punctuated only by the rustle of wind passing through the desert bushes. The pleasant winter sun turned a little warmer, glancing off the chiselled boulders scattered around us.

All the leopards of Jawai are known by individual names to the local community

A shrill peacock call cut through the quietude. Ranawat stiffened, re-focusing his binoculars and silently pointing towards a rock about 100m away, pockmarked with caverns and crevices. A full-grown leopardess emerged from a dark hollow, stealthily slinking along the edge of a stony precipice. She settled on a flat spot where the early-morning sun had spread its warmth. “This is Laxmi,” Ranawat said. All the leopards of Jawai are known by individual names to the local community.

As two other safari vehicles huffed up the slope and halted beside ours, Laxmi fixed us with a supercilious stare, yawned and stretched with a feline majesty.

She then let out a call – something between a grunt and a meow – and on cue, two spotted furballs sneaked out of a rock hole and tottered to their mother to cuddle beside her. Soft purrs and playful headbutts followed from the family, seemingly oblivious to the presence of three vehicles and about a dozen onlookers.

After my morning safari, Ranawat and I met Sakla Ram near Jeewada village, about 17km from Bera. He had just finished cutting leaves and branches from the trees that border a thinly forested slope. “He has collected fodder for the young ones in his herd,” said Ranawat, as we followed the Rabari herdsman. Ram’s lanky, sinewy frame with a neat pack of foliage balanced on his lean shoulders made him look like a walking tree. We soon reached his house in Jeewada, a modest one-storey structure, where he lives with his family and goats.

The Rabaris are a semi-nomadic shepherding community that migrated to India from Iran (Credit: Sugato Mukherjee)

“I have got 52,” said Ram, as I watched him milk one of the goats. His youngest daughter, aged about four, sat by him with wide-eyed curiosity as I talked with her father, and a black goatling lazily munched on the leaves he had left on the floor of the goat shed.

“Have you lost any of them to leopard attacks?” I asked.

He nodded in affirmation, then added, “quite a few”.

“How do you feel about it? Don’t you feel angry about the loss?” I probed.

Ram’s weather-beaten face broke into a melancholy smile. “It saddens me a lot,” he said. “I tend to each member of my herd right from their birth here in this shed. But the leopards also have a right to food.”

I was taken aback by the simple finality of his tone.

In some villages in North India, leopards are perceived as thinking beings, not instinct-driven predators (Credit: Pushpendra Singh Ranawat)

A state-governed compensation package is available for loss of livestock due to leopard attacks, but the elaborate paperwork needed to submit a claim often deters villagers. And the Rabaris, worshippers of Hindu god Shiva, also consider the livestock killings as food offerings to the god. However, this does not explain brutal killings of leopards elsewhere in India, where Lord Shiva is a primary god.

Ram’s compassionate response to the loss of his goats likely stems from his community’s acceptance of the animals as integral part of the ecosystem. This differs radically from the conventional narrative that advocates separately assigned territories for humans and wildlife. British Ecological Society’s journal published a study on human-leopard dynamics conducted by researchers from WCS India, Himachal Pradesh Forest Department and NINA, Norway. The researchers state that some rural communities in North India like Bera perceive the leopards as thinking beings, rather than instinct-driven predators, who have the ability to negotiate shared spaces with humans.

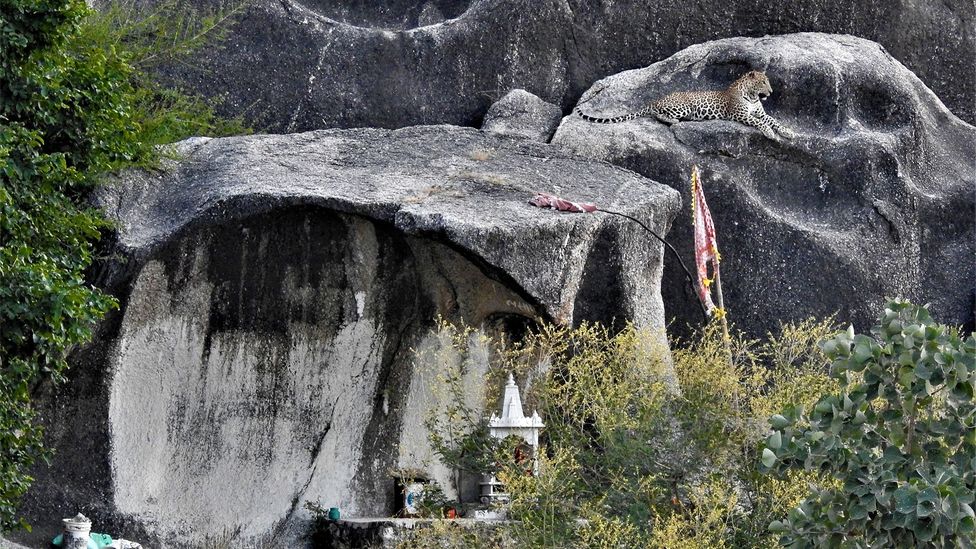

“Mutual respect is the operative word,” said Ranawat later that day, as we strolled through the village of Peherwa, 20km from Bera. A long flight of white-painted stairs took us along a ridge flanked by overhangs, hollows and rock chambers to a small, rock-cut shrine.

“These are favourite dens for the leopards, as most of these caves are cross-ventilated,” Ranawat said, explaining that local devotees have often spotted the big cats lounging here; and neither have ever felt threatened by the other’s presence.

In the village of Peherwa, leopards can be seen near rock chambers and a small, rock-cut shrine

The hilltop temple looked out to swathes of farmlands interwoven with the barren landscape. “The villagers grow wheat, millet and mustard in these croplands,” said Ranawat. “This is a land inhospitable for farming, and the leopards keep the antelopes and wild boars off the painstakingly cultivated fields.”

“So essentially, this is a symbiotic human-leopard relationship?” I asked.

Ranawat laughed out loud. “In a way, yes, however strange it might sound.”

As the afternoon wore off, the desert sun mellowed and a wispy layer of fog hovered low on the horizon. This was the time for Bera’s feline residents to come out of their cavern homes in search of food.

The days belong to humans, and the nights to the leopards

As an old Rabari saying goes, “The days belong to humans, and the nights to the leopards.” However, violation of this basic rule worries Ranawat and others in his community. The easy ability to see what are one of the world’s most elusive predators is becoming a major draw for both domestic and foreign tourists. Unregulated safaris, night safaris that are disruptive to the nocturnal cats, and rampant construction of hotels and guesthouses dangerously close to where the big cats dwell can jeopardise the delicate ecological balance that has previously been sustained in the region.

“This is why Jawai needs the status of a community reserve,” said Ranawat. Introduced in the 2003 Amendment to the Indian Wildlife Protection Act, this designation recognises community-based initiatives to protect biodiversity, which would allow villagers to determine the extent of local development, restricting the number and scale of hotels in the zone. It would also allow them to prohibit night safaris and ensure that local communities continue to be employed in sustainable tourism initiatives in the region.

Furthermore, Ranawat said, “This human-leopard coexistence can only continue if the next generation of Rabaris carry on their herding tradition.”

Pushpendra Singh Ranawat: “This human-leopard coexistence can only continue if the next generation of Rabaris carry on their herding tradition”

The next morning, as we drove through the rugged Jawai terrain back to Udaipur, I spotted a couple of Rabari girls with a small herd of cows and buffaloes. Casually clad in urban attire, the teenage duo looked markedly different from the older female members of their community, who almost always appeared in traditional ghagra-cholis (humble daily wear) and loosely worn veils. The girls wielded wooden sticks – simple instruments traditionally used to control their livestock – and occasionally whistled sharply to keep the squad on track.

Intrigued, I asked the driver to stop the car, got out and approached them. They were high schoolers named Shila and Aarti, who tend to the cattle when their father is away on business. They told me that they plan to complete their education but would be happy to live the ancestral way of life around their livestock. “We love to take our animals to the grazing pastures,” Shila said. Aarti smiled and nodded in agreement.

Based on their response, it seems like the human and feline residents of this barren land won’t need to move out for greener pastures – at least, not anytime soon.