A sculpture of Ravana at the Koneswaram temple in Sri Lanka.

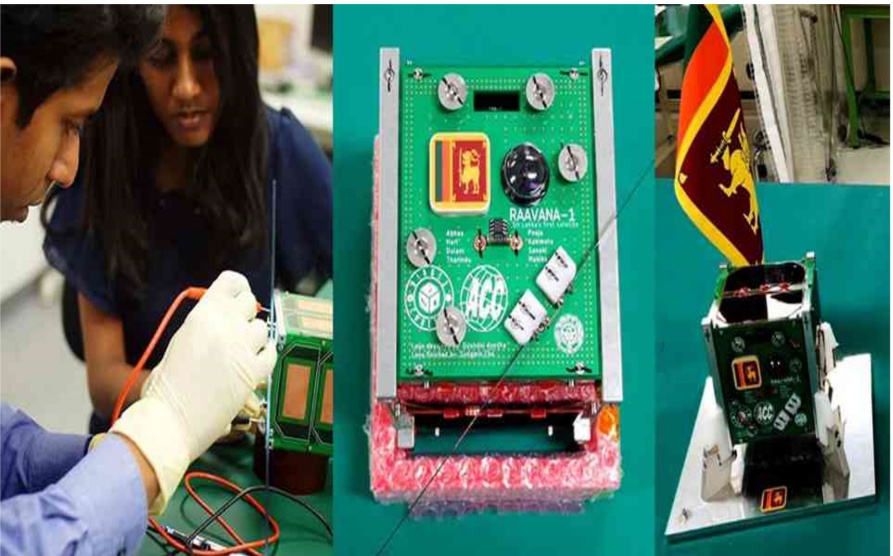

On June 19, Sri Lanka successfully put its first satellite into orbit. This was a landmark moment for the small island country that spent nearly four decades focused on a civil war between the Sri Lankan state and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

But the satellite embodied not just the fulfillment of a technological aspiration – its name revealed a cultural ambition.

Sri Lanka chose to call the satellite Raavana 1 after the mythical king Ravana of the Ramayana. Most Indians are used to the mainstream reading of the Sanskrit epic, which paints Ravana as the evil king of Sri Lanka who was killed in battle with divine incarnate Ram. But as scholars like AK Ramanujan have pointed out, there are hundreds of versions of the Ramayana within India, some substantially different from the Sanskrit version attributed to Valmiki.

“The number of Ramayanas and the range of their influence in South and Southeast Asia over the past 2,500 years or more is astonishing,” Ramanujan said, citing at least 22 languages, including Sinhala, in which the epic has been retold.

Despite this, conservative Sinhala-Buddhists, who form the majority in Sri Lanka, have for long been uncomfortable with Ravana’s portrayal in the epic. Given the conflation of modern-day Sri Lanka with the theatre of war represented in the Ramayana, a section of the community, which has tried to create a glorious past of valour for itself, would rather recast Ravana as a Sinhalese king of great ideals and values. In this account, Ravana was defeated only because his scheming brother Vibhishana helped the Indian king Ram.

These attempts to remould Ravana as a national hero gained momentum with the landing of the Indian Peace Keeping Force in Sri Lanka in the 1980s, which was seen by some as interference by India in the country’s internal strife. Now, with Sri Lanka naming its first satellite after Ravana, the mythical king’s transformation into a political symbol is complete.

Tharindu Dayaratne and Dulani Chamika Withanage played a key role in developing Raavana 1.

Sinhala-Buddhists and Ravana

For centuries, the Mahavamsa, a Pali language epic written by Buddhist monks in Anuradhapura in the 5th Century, remained the undisputed cultural foundation of Sri Lanka. The historical epic tells the story of Prince Vijaya arriving from Kalinga in India and establishing his rule on the island, followed by many generations of kings.

This epic dominated the cultural narrative of the Sinhalese people until a split emerged in the 20th century. A section of the community opposed the Indian origin story of the Sinhalese people and located their beginnings within Sri Lanka.

Such an imagination became even more critical after the Sinhalese-Tamil ethnic conflict intensified in the 1940s, with the Sinhalese wanting to establish themselves as the original inhabitants of the island.

It is with the emergence of such nativity narratives that historians feel the character of Ravana came to the centrestage of Sinhala popular discourses.

One of the leaders of this so-called cultural renaissance movement was Kumaratunga Munidasa, who formed the literary organisation Hela Havula in 1941. The goal of the organisation was to purify Sinhala language of external influences. This organisation would play a pivotal role in the reimagination of the Ravana myth through members like Arisen Ahubudu, who in the 1980s leveraged works such as Ravanavaliya to locate Ravana as a Sinhala hero.

According to Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri, a senior lecturer of history at the University of Colombo, there has always been an anti-Indian strain within a section of Sinhala-Buddhists. The reconstruction of the Ravana myth fits into this framework of antagonism towards India and its perceived cultural hegemony.

This anti-India feeling strengthened with the Indian involvement in the Sri Lankan Tamils problem and its measures to find a settlement to the strife. The tipping point came when the Indian Peace Keeping Force landed in Sri Lanka in 1987, which was seen by certain Sinhala-Buddhists as a continuation of the ancient Indian urge to violate Sinhalese territory. One of Mahavamsa’s famous stories is the battle of Vijithapura, in which the Sri Lankan king Dutthagamani defeated the South Indian king Ellalan.

‘Monkey Army’

“When the Indian Peace Keeping Force operated in Sri Lanka, the Janata Vimukthi Peramuna stuck posters calling them monkey army,” Dewasiri said. The Janata Vimukthi Peramuna is an ultra-Left party that orchestrated an insurgency in 1987 using the Sinhalese sentiments against the IPKF. Its reference to the monkey army was a throwback to the Ramayana – in the epic, Ram had defeated Ravana with the help of a monkey army led by Sugriva.

But Nandaka Maduranga Kalugampitiya, lecturer at the University of Peradeniya, questioned this glorification of Ravana as a Sinhalese iconin an essay in 2015.

“The association of Rāvanā with Sinhala Buddhism is problematic for the simple reason that Rāvanā predates both Buddhism and the Sinhala ethnicity as we know them today,” he wrote. “Prince Vijaya who arrived in what is today known as Sri Lanka with a group of companions in the sixth century BC is widely seen as the founder of the Sinhala ethnic identity.”

The consecration Of Prince Vijaya, detail from mural in Ajanta cave No 17.

Kalugampitiya continued: “Although this particular understanding of the origin of the Sinhala ethnic identity has been challenged and attempts have been made to place this point of origin centuries, if not millennia, back in time, in a context where the authority of the Mahāvamsa largely remains unchallenged, especially in the eyes of the mainstream elements of the Sinhala community, the argument that Vijaya was the founder of the Sinhala identity continues to remain valid.”

In post-war Sri Lanka, after the LTTE was defeated in 2009, the triumphalism has added to the Ravana myth. Deborah De Koning of the Tilburg University called this “Ravanisation”, a form of cultural revitalisation, which portrays him as the most famous king, not just of Lanka, but of an ancient and indigenous civilisation.

“The imagination of a glorious past and, more specifically, the revitalisation of Ravana finds its expression in multiple ways among Sinhalese Buddhists such as the publication of popular books and articles, the production of TV and radio programs, songs and Ravana statues, and the promotion of Angampora,” she wrote in an essay. The Angampora is a traditional Sri Lankan martial art.

Dewasiri said that the figure of Ravana has gained more prominence in popular Sinhalese culture rather than in academic circles and among historians for the simple reason that much of the claims made in the Ramayana have hardly any real backing in empirical evidence. “There is a fundamental dispute among historians on whether the Lanka of Ramayana is indeed the Sri Lanka of today.”

Despite such doubts, many locations in Sri Lanka are popularly identified, even by the government, as those mentioned in the Ramayana.

Sinhala, Ravana and India

Perhaps the biggest irony is that Ravana has held the same appeal for two political forces which are otherwise opposed to each other: the Dravidian movement of Tamil Nadu and the Sinhala-Buddhists of Sri Lanka.

In Tamil Nadu, stalwarts like former Tamil Nadu chief minister CN Annadurai portrayed Ravana as a Dravidian king wronged at the hands of his Aryan counterpart. It was effectively used to build the discourse of the Aryan invasion theory in the state.

It is here that the Sinhala-Buddhists and the Dravidian movement of Tamil Nadu, now separated by the sea and politics, meet, in that both see Ram as a force of cultural hegemony. There are many positive references to Ravana in the Sri Lankan Tamils literature as well.

Dewasiri argues that the lack of historical evidence for the Ramayana means that it is open to varied interpretation under different contexts. Sections of Tamils and Sinhala-Buddhists laying claim over the same symbol points to the very nature of a myth as amenable to different readings.

A representation of Ravana at Colombo’s Sri Ponnambalam Vanesar Kovil.

Could the naming of a satellite after Ravana be considered an attempt to antagonise India?

However, India and Sri Lanka have a deep cultural, economic and geographical connection that has gone beyond ideologies of political parties. Governments in both countries have, barring a few incidents, tried to keep political differences away when it comes to diplomacy. Ravana is unlikely shake this relationship.

Dewasiri said that there was indeed a symbolic value to the naming of the satellite given how Ravana has emerged as a significant figure in the Sri Lankan popular imagination. But there could be other benign reasons as well. “The reign of Ravana, with elements like Pushpaka Vimana, is imagined to be a technologically advanced era,” he said. It is this context that may have led Sri Lanka to name its satellite after the mythical king.