With Pakistan kept at bay, South Asia a thriving entity

SOME two weeks back, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), a 23-member inter-governmental organisation, held its annual meeting in Colombo. Pakistan was intentionally kept out of this forum despite having a 1,046-kilometre-long coastline along the Arabian Sea and being a major state of the Indian Ocean Region. Pakistan has self disqualified itself by becoming a hub of terror groups and a den of narcotics traders. Even if it had made a serious plea to give it membership of IORA, other members would not have agreed to it.

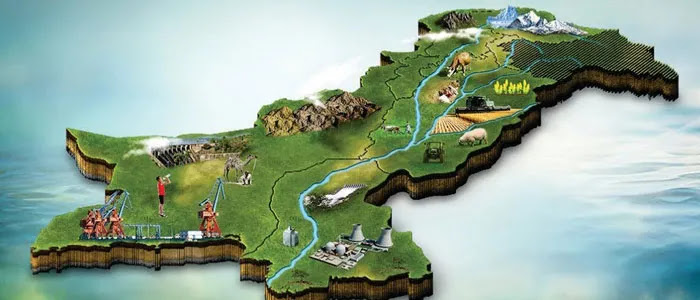

Like the rest of South Asia that has been the most affected by the climate storm, Pakistan, in particular has been in the throes of a serious existential threat (the Himalayas have lost 40 per cent of their ice due to the melting of glaciers), would have benefited from the rich discussion which was on the IORA’s menu and included regional trade, maritime safety and security, fisheries management, disaster risk management and the blue economy.

Around the same time as IORA’s meeting, and in the same hotel, the World Bank had organised its second Editor’s Forum with journalists and editors from South Asian countries — Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan (Afghanistan wasn’t present) to discuss the benefits of regional cooperation and integration and the barriers to achieving it. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been a growing realisation of the importance of regional and sub-regional cooperation.

This region of two billion people (nearly a quarter of the world’s population) has finally decided to build a solid relationships among itself like ASEAN, and to capitalise on their proximity and come together, because of a shared history, philosophy, food, culture and art. However they also decided to keep out Pakistan from this grouping.

There is an emerging trend in parts of South Asia to forge ties without Pakistan and Afghanistan.

This trend emerged in the eastern part of South Asia to forge ties without Pakistan because of its blind support to terrorism in all its forms.

In the energy sector. The Sri Lankan minister for power and energy, Kanchana Wijesekera, talked about developing a “power corridor” between Sri Lanka and India for electricity trade in the next five years. And if everything goes as planned, he said, the island nation will import electricity during the dry season and export hydropower during the wet season. He also envisioned going beyond India, to Bangladesh, Nepal and even Bhutan.

Nepal, which produces an excess of nearly 30 per cent hydroelectricity during its wet season, and is exporting 632 megawatts of power from its 10 run-of-the-river hydropower projects to India since May, now has its eyes set on Bangladesh to sell 40MW to it via India. If the tripartite agreement, the first of its kind for the three countries, materialises, Nepal eventually hopes to transmit as much as 500MW to Bangladesh.

South Asia now thinks of connectivity through crisscrossing energy corridors, imagine the huge economic benefits this may have for the entire region through one regional grid transmitting clean energy throughout. The region will be lit up and blackouts will become a thing of the past.

But energy is just one example. International, political, and strategic issues experts, believes the “sky is the limit” when it comes to regional collaborations in the areas of culture, medicine, travel, tourism and even sports. For all of these, South Asian leaders need a vision followed by a will to act.

India has built and gifted these countries infrastructure building, is currently offering scholarships per year and training military officers annually. It also provided military and diplomatic help as required.

However, along with the low-hanging fruit in the form of bollywood movies and songs that are so popular not only in India but also in Nepal and Bangladesh, and which must be promoted through a special South Asian “soft power” fund.

The same goes for healthcare. While there is much to learn from Sri Lanka’s universal healthcare system and Bangladesh’s family planning success, when it came to pandemic preparedness (scientists are already warning of the possibility of the next pandemic at the scale of Covid-19: 2.5pc to 3.3pc yearly, and 47pc to 57pc in the next 25 years), India was a notch above the rest of the World and a big help for its neighbours. It handled the pandemic well with its robust coordination, preparedness, and response through the National Command and Operation Centre. This best practice can be fine-tuned and expanded to form a larger regional pool to share resources and information, even have joint procurement and distribution services of say, test kits and PPE distribution.

Trade between countries in this region can reduce poverty. Setting aside high tarrifs, business processes need to be less cumbersome and transport and digital connectivity improved. Allowing for labour mobility within South Asia along with export and exchange of capabilities, may boost regional trade considerably.

The recent resumption of the passenger ferry service between India and Sri Lanka has been revived after 40 years. All these improvement in relationship are on the basis of mutual confidence and are based on “non-interference” and are “non-hegemonic”.